Roots[1]

Like most post-World War Two liquid-fueled missiles, the Al Hussein had its roots in the German V-2 rocket program. The Soviets, like their erstwhile American and British allies, were very interested in gaining access to the technology and scientists associated with the V-2 project. In the immediate aftermath of the war, the Soviet Army rounded up nearly 200 German specialists affiliated with the V-2 program to reconstitute a V-2 production line. In May 1946, responsibility for establishing a Soviet ballistic missile production capability was formally granted to Dmitri Ustinov, the Minister for Armaments, who took control of the reconstituted V-2 program and moved it onto Soviet territory. By 1947 Ustinov had established two German-run facilities, one a test launch range at Kapustin Yar, and the other a missile research and development center located on Gorodomlya Island, north of Moscow which built and tested the R-1 rocket (known in the West as the “Scunner”).

The German missile program was part of an entity known as Scientific-Research Institute (NII) No. 88. Around 170 German scientists, led by their chief designer, Helmut Groettrup, constituted Branch 1 of NII-88, responsible for brainstorming technical improvements in the V-2 design. But Ustinov had also tasked a separate section, known as Experimental Design Bureau (OKB) No. 1, under the direction of a Russian engineer named Sergei Korolev, to take the German research and build a purely Soviet long-range rocket. While the German rocket scientists were involved in the early testing of the R-1 at Kapustin Yar, beginning in 1948, starting in 1951 the German scientists were separated from their Soviet counterparts as the Russians began to advance their own designs. By 1953 the scientists and their families began to be repatriated back to Germany.[2]

As Minister of Armaments, Ustinov oversaw the work of the Germans, Korolev and other engineers and institutions as they built from the ground up what would become the Soviet ballistic missile enterprise. While Korolev went on the spearhead the Soviet space program, one of his chief designers, Viktor Makeev, developed a new family of tactical ballistic missiles, known in the West as the SCUD-A, using the work done by OKB No. 1 and NII-88. Ustinov subsequently appointed Makeev to head up his own design bureau, which was collocated with the Zlatoust Machine Building Plant, located in Chelyabinsk Oblast, the southernmost part of the Ural Mountain region, to produce the SCUD-A missile.

Makeev followed up the success of the SCUD-A with a follow-on design, the SCUD-B. Makeev perfected the SCUD-B design through trial and error in 1957-1958, finally producing a variant which met the requirements of the Soviet Army. Ustinov, however, decided that Makeev’s skills needed to be singularly focused on the emerging problem of designing and building submarine-launched ballistic missiles. Instead, the SCUD-B production line was transferred from Zlatoust to the Votkinsk Machine Building Plant. Missile flight tests began in 1959, and in 1964 the system was accepted by the Soviet military. Over the course of the next 25 years, the Votkinsk Machine Building Plant produced tens of thousands of these missiles for service in the Soviet Army and for export to Soviet allies.[3]

One of these allies was Iraq.

Soviet ties to Iraq date back to July 14, 1958, when the pro-British Hashemite monarchy was overthrown by Brigadier General Abd al-Karim Kassem. Kassem’s attraction to the Soviets came in his desire to sever Iraq’s relations with both Great Britain and the United States, and his willingness to make an ally of the Iraqi Communist Party to achieve his domestic and regional political ambition. The first Soviet-Iraqi arms deal was signed in November 1958. While the new Iraqi regime eventually had a falling out with the Iraqi Communist Party, shutting it down in 1960 and executing its leaders, the Soviets opted to continue selling arms to the Iraqis, hoping that through the arms trade they might be able to influence Iraqi regional policy. When the radical wing of the Iraqi Ba’ath Party overthrew Kassem in February 1963 and began a process of purging the Iraqi Communist Party, killing over 3,000 party members, the Soviets ceased all arms transfers in protest. Only after General Abd al-Salem Arif stepped in and drove the Ba’ath Party from power, in November 1963, did the Soviets resume arms deliveries, starting in June 1964.

Soviet-Iraqi relations grew even closer following Israel’s decisive victory over an Arab coalition led by Syria and Egypt, but which also included Jordan and Iraq. After the war, Iraq began forward deploying forces into both Syria and Jordan, increasing its demand for more Soviet weaponry. In 1968 Iraq began working with the Soviets to develop the North Rumaila oil field, enabling Iraq to begin marketing its oil independent of western oil companies. However, when the Ba’ath Party swept back into power, launching a bloodless coup on July 17, 1968, that saw Arif replaced by Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr, Soviet-Iraqi relations chilled.

In November 1969 al-Bakr sought to end the influence of the Iraqi Army in domestic political affairs by expanding the size of the governing Revolutionary Command Council (RCC) from five to fifteen, bringing in an influx of civilians led by Saddam Hussein. When the Army attempted a coup in January 1970, it was thwarted by Ba’athist security forces led by Saddam Hussein. Freed from the pressure brought to bear on Iraqi policy, both foreign and domestic, by the Iraqi Army, the Ba’ath Party, increasingly influenced by the moderate, pragmatic thinking of Saddam Hussein, began a policy of rapprochement with the Soviets which led to the renewal of large-scale arms sales in 1972.

1973 Iraq concluded its first contractual agreement with the Soviet Union for the purchase of the SCUD-B missile system. The decision to sell the SCUD-B in its export configuration (designed to be used with a conventional high explosive warhead, as opposed to a nuclear warhead—the nuclear missile was around 50cm longer than its conventional counterpart to accommodate some nuclear-specific electronics) was reflective of a Soviet policy which saw the need for Iraq to be prepared to fight a war with both Israel and Iran.

The sale involved a complete Soviet-style SCUD-B Brigade. In addition to the delivery of 115 operational SCUD-B missiles, delivered between 1974 and 1979 (45 missiles in 1974, 42 missiles in 1978, and 28 missiles in 1979), the Iraqis procured ten MAZ-543 transport erector launchers (TELs) and the various associated components (fuel, spare parts, and auxiliary equipment) to outfit a standard Soviet-style SCUD-B brigade. The contract also provided for the training of Iraqi personnel at the Kazan Missile Training School, where they received basic operation and maintenance instruction on the SCUD-B system. Among the first officers sent to Kazan for training was a young captain named Hazem Abdul-Razzaq Shihab Ayoubi.

A contingent of Soviet missile experts were dispatched to Iraq along with the initial delivery of material in 1973. The Iraqi SCUD-B Brigade, known by its designation as Unit 224, was organized into three battalions, each equipped with three MAZ-543 TELs. The tenth MAZ-543 TEL was used as an operational trainer for an Iraqi surface-to-surface missile school, established in Abu Ghraib. In addition to the launchers and missiles, the Iraqis received 18 missile transport trailers (six per battalion, or two per launcher), six fuel tankers (two per battalion), 12 oxidizer tankers (four per battalion.) Both the fuel tankers and the oxidizer tankers were mounted on modified ZIL-131 vehicle chassis.

In addition to the three operational battalions, Unit 224 had a technical battalion which was equipped with three autonomous test vehicles and horizontal test vehicles. Both testing systems were mounted on URAL-375 chassis. The autonomous test vehicles were used to test the electronic systems of the TEL and missile prior to launch, and the horizontal test vehicles were used for test checks run on the gyroscopes of the guidance and control systems used on the SCUD-B missiles prior to their installment on an operational missile.

The five-year contract between Iraq and the Soviet Union also provided for a supply of the fuels used in the rocket engine. The amounts shipped were based upon a supply “norm” established by the Soviet Army. The SCUD-B missile used three types of liquid propellant—TM-185 Main Fuel (a hydrocarbon fuel comprised of polymeric distillates and light pyrolysis oils, one metric ton per missile), TG-02 Starter Fuel (tri-ethylene, .35 metric tons per missile), and AK-27 Oxidizer (Nitric Acid oxidized to 27%, 3.513 metric tons per missile).

In addition to the missiles and fuel supplies, Iraq’s contract with the Soviet Union provided for replacement parts and equipment. These components were provided to Iraq based upon pre-planned “norms” established by the Soviet Chief Designer in consultation with the Soviet Army and was based upon anticipated failure rates over the service life of the missile. Accordingly, for every 25 missiles shipped, Iraq was provided with a “group set”, or ZIP, consisting of a complete guidance and control package, fuel and oxidizer drain valves, pyrotechnic devices, and other assorted components. ZIP sets were retained by the Technical Battalion of Brigade 224, as was a specialized spare parts vehicle, a modified ZIL-157 designed to serve as a mobile repair and maintenance unit for use by the technical battalion in a field environment.

Iraq also received 15 training missiles, as well as full-scale and 3/4 scale mock-ups of the SCUD-B engine and a full-scale cut-away model of the SCUD-B missile and engine. These items were used by the technical battalion for training purposes. In 1978, as the initial cadre of Iraqi officers returned from their training in Kazan, the Iraqi military decided that it would open its own surface-to-surface missile school. An additional MAZ-543 TEL was procured for this purpose, and the technical battalion’s training function was transferred to the new academy, which was established near Abu Ghraib, just west of Baghdad.

In 1979, when the last Iraqi troops and officers completed their instruction at Kazan, the Soviet contract ended, and the Soviet missile specialists working in Iraq departed, having fulfilled their mission of helping Iraq establish an infrastructure to support its ballistic missile force. This infrastructure included the establishment of a Brigade Headquarters and Barracks Camp at Khan Al Mahawil, south of Baghdad, and a Technical Support Camp, comprising the technical battalion and missile storage unit, located at the Taji military complex, just north of Baghdad. The Abu Ghraib surface to surface missile school, equipped with training launcher and training missiles, provided Iraq with the indigenous capability to sustain the training and support requirements of Unit 224 going forward.

While the training provided by the Soviets at the Kazan academy gave the Iraqi missilemen good theoretical knowledge about the operations of the SCUD missile, practical experience in the form of firing a SCUD missile had to wait until Unit 224 had accumulated enough qualified personnel to permit live-fire drills in Iraq. Under the watchful eyes of their Soviet advisors, Unit 224 conducted a total of six launches of a SCUD missile in 1976 and 1977, part of what the Soviets called “basic targeting” drills. The Iraqis shipped two of its SCUD missiles to the Soviet Union to be used in “basic targeting” drills marking the graduation of the final class of Iraqi missilemen in 1979. At the beginning of 1980, the men of Unit 224 stood fully ready to carry out operational combat duties. They proved this during two more “basic targeting” live fire drills.

They didn’t have to wait long. On September 22, 1980, Saddam Hussein ordered the Iraqi Army to invade Iran, initiating what would turn into an eight-year nightmare for both nations. Under Soviet doctrine, the SCUD-B was a battlefield support weapon, designed to be used against enemy command and control centers, troop assembly areas, and rear area logistics concentrations. While the Soviets had invented the SCUD-B, as of 1980 the only time the SCUD-B had been used in actual combat was when, on October 22, 1973, the Egyptian Army, with the support of Soviet advisors, fired three SCUD-Bs against Israeli troop concentrations around the Suez Canal in the closing hours of the Yom Kippur War.[4]

The Iraqi Army likewise employed their SCUD-B missiles according to Soviet doctrine, targeting Iranian supply depots, command posts, and troop assembly areas in support of the Iraqi advance and later, when the Iranian defense stiffened and the frontlines became fixed, in support of Iraqi defensive operations. Some 68 missiles—over half of the Iraqi inventory—were expended in 1980, making Unit 224 the most operationally experienced SCUD-B unit in the world.

The operational tempo of Unit 224 slowed down considerably in 1981, dictated both by the realities of the battlefield (fewer doctrinally acceptable targets) and the diminishing number of missiles in the Iraqi inventory. Unit 224 expended 31 SCUD-Bs in 1981, leaving a scant 6 missiles on-hand by years end.

Starting in 1982, the Iraqis began reaching out to the Soviet Union military to negotiate a new contract for the delivery of SCUD-B missiles. The Soviets informed the Iraqis that production for the export version of the SCUD-B was finite. While there continued to be demand for the missile from foreign governments, the primary consumer was the Soviet Army, where the SCUD-B was being phased out in favor of the SS-23 “Oka” short-ranged ballistic missile. Production lines in Votkinsk that were once used to manufacture the SCUD-B engine and airframe were being converted for use in manufacturing the SS-23.

The Iraqis agreed to a five-year open credit covering the years 1982-1985, where they had agreed to buy whatever SCUD-B missiles the Soviets had on hand. The Soviets would notify the Iraqis that missiles were available, at which point a contract would be drawn up, and the missiles delivered. Using this methodology, 30 missiles were delivered in 1982, 45 in 1983, 135 in 1984, 55 in 1985, 96 in 1986, and 306 in 1987.

The role of the SCUD-B in the Iraqi concept of operations changed as well. The expense associated with buying new missiles, when combined with the changing nature of the war, helped transition the Iraqi Army away from using the system in its doctrinal role of battlefield support, and to a weapon of strategic importance, where a missile could only be launched at a target that had been approved in advance by Saddam Hussein himself. The Iraqi SCUD-B became a weapon designed to punish a recalcitrant Iranian civilian population, and in doing so, sought to undermine popular support against both the war and the government of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

All in all, Iran fired 29 SCUD-B missiles against Iran in 1982, followed by another 41 in 1983. Almost all of these were against front-line Iranian cities. Thousands of Iranian civilians were killed. The city of Dezful was singled out for punishment. Located some 80 kilometers from the border with Iraq, Dezful was a thorn in the side of the Iraqi invading force, a transport and logistical hub that allowed Iran to push troops and material to the frontlines with relative ease. Unable to defeat the Iranian military on the Dezful front, the Iraqi leadership decided to take its frustration out on the civilians who lived in the city.

On October 27, 1982, Iraq began the bombardment of Dezful, firing three SCUD-B missiles into the city. Twenty-one civilians were killed, and over 100 wounded. The strikes continued in 1983. In February, a SCUD-B struck the city, collapsing an apartment building and killing scores of civilians. Unit 224 struck Dezful again on April 20, April 22, and May 12. By the time a United Nations investigation team visited Dezful in May 1983, the city had been struck more than 6,000 times by artillery, aerial bombardment, and missiles strikes, including both FROG-7 and SCUD-B. More than 600 people had been killed, and more than 2,500 injured.

Unit 224 launched 41 SCUD-B missiles at Iran in 1983, all of them against civilian targets. Another 74 SCUD-B missiles were launched in 1984, followed by 119 in 1985. Unit 224 stood down in June 1985 as part of a strategy of de-escalation pursued by Saddam Hussein. As a result, Iraq fired no SCUD-B missiles in 1986. Instead, Iraq sent feelers out to the Soviet Union, seeking to acquire missiles possessing a range of around 600 miles (965 kilometers.) The initial Iraqi request was to purchase the SS-12 SCALEBOARD intermediate-range missile. It used the same TEL—the MAZ-543—as the SCUD-B and had the extra benefit of being solid-fueled, making launch operations simpler and faster. When the Soviets refused, the Iraqis made a pitch for the SCUD-C, a liquid fuel missile like the SCUD-B. Again, the Soviets refused the Iraqi request.

Iraq’s incessant missile strikes against cities like Dezful had prompted Iran’s leadership to obtain the ability to strike back against Iraq. In mid-1984, a delegation of officers from the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps travelled to Syria, where they underwent a three-month period training at the hands of the Syrian Army on the operations of the SCUD-B missile. The Syrian SCUD-B missiles, however, were closely monitored by Soviet advisors, and the Syrian government was no able to provide and launchers or missiles for Iran’s use. The Libyan government of Muammar Ghaddafi, however, had no such qualms. The Libyans agreed to provide Iran with four MAZ-543 TELs and 8 SCUD-B missiles, along with Libyan crews, who would be responsible for their operation.[5]

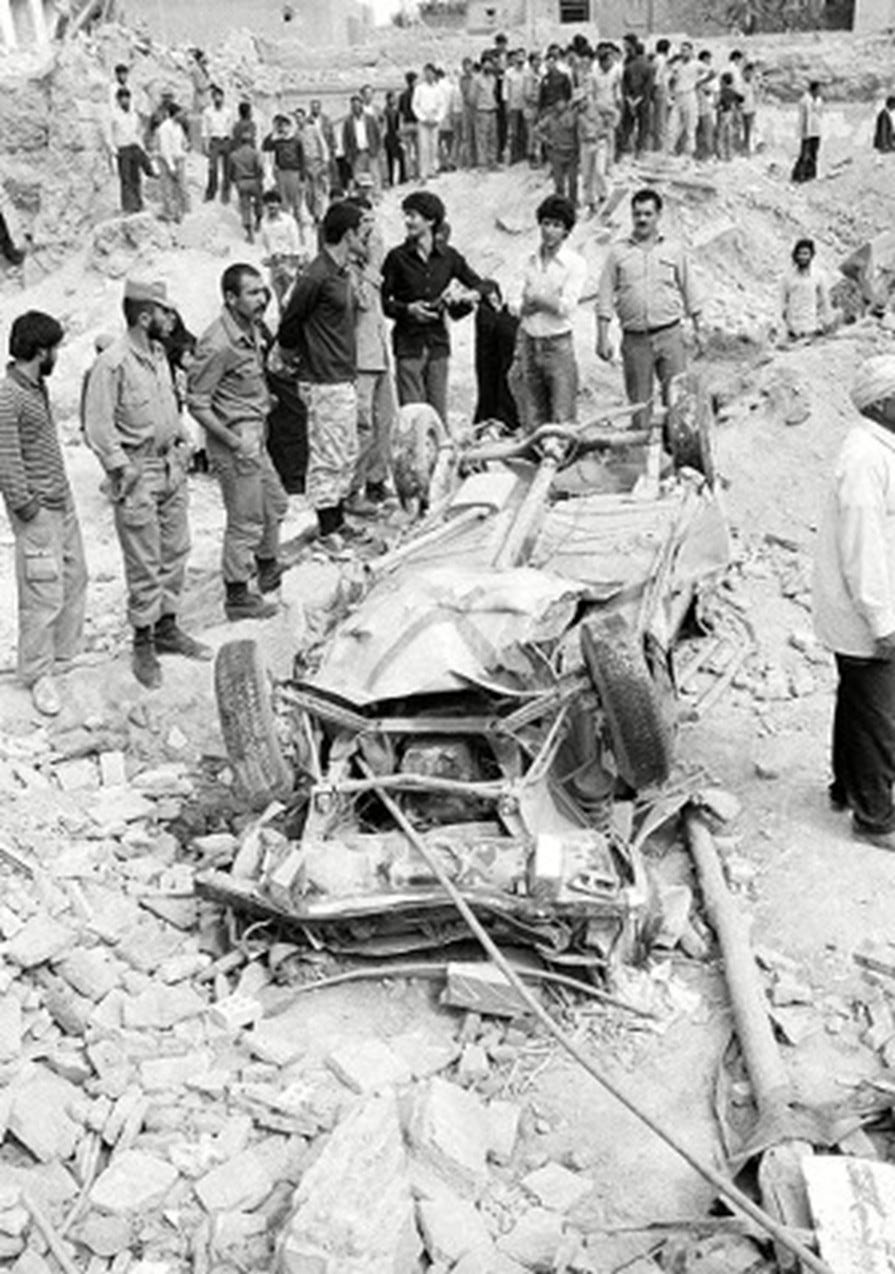

In March 1985, the Libyan crews fired the initial salvos of SCUD-B missiles into Iraq. On March 14, a SCUD-B struck the 12-story main building of the Iraqi government-owned Rafidan Bank, causing an explosion that could be heard miles away while causing a giant fireball that had ambulances and firetrucks driving frantically to the scene. The Iraqi government tried to deny the Iranian missile attack, attributing it instead to “agents of the Iranian regime” who had planted a bomb.[6] Missiles continued to rain down on Baghdad, including one which struck an overpass of a major highway intersection, collapsing a section of the highway, crushing several cars in the process.[7] Iraq again denied that it had been struck by an Iranian missile. However, by May 1985 the attacks had become so incessant that the Iraqi government could no longer deny what was becoming obvious to all—Iran had its own force of SCUD missiles that was wreaking havoc on the Iraqi capital.[8]

Impressed with the results, Iran purchased 22 more missiles, for a total of 30. The Libyans ended up launching some 14 SCUD-B missiles against Iraq in 1985, with the majority aimed at Baghdad. These launched continued into 1986, with another seven SCUD-B missiles being launched by Libyan crews into Iraq. By early 1986, however, Libya was engaged in a growing crisis with the United States which culminated in an American air strike against Libya on April 14, 1986. The next day, April 15, Libya retaliated by firing two SCUD-B missiles at a US Coast Guard facility located on the Italian island of Lampedusa; both missiles missed their target, landing harmlessly into the Mediterranean Sea. Muammar Ghaddafi recalled the Libyan missile crews from Iran to bolster his defenses at home. Iran, using its own crews, fired a single SCUD-B at Baghdad, but faced with a diminished inventory of SCUD-B missiles (only eight remained), the Iranians halted missile operations until a new source of SCUD-B missiles could be found.

The Iranians hit pay dirt with North Korea, where they helped underwrite North Korean efforts to build a factory to produce SCUD-B clones known as the Hwasong-5; an initial delivery of 40 of these North Korean missiles arrived in Iran in June 1987. By October 1987 the Iranian missile forces were ready to resume operations using their new North Korean Hwasong-5’s. On October 7, the Iranians fired a single Hwasong-5 at Baghdad, and over the course of the next several days, fired two more. These missiles appeared to have done little damage.

On the morning of October 14, the Iranians fired a fourth Hwasong-5.

At 7.55 am, hundreds of Iraqi schoolchildren had assembled in the playground outside the Martyr’s Place Elementary School, in downtown Baghdad. They were singing songs in preparation for beginning the school day when the Iranian missile scored a direct hit on their school; 29 children were killed, and 196 others wounded (3 adults were also killed, along with 22 injured.) Parents quickly gathered on the grounds of the destroyed school, wailing in grief as the bodies of the children were pulled out from beneath the rubble.

An Iraqi government communique condemned the attack, declaring “Iraq’s right and duty to reply to this heinous crime. They want a ‘war of the cities’ and they will get it. Missiles will make them understand.”[9]

The Missile of Arafat

The Iraqis were not bluffing. Nearly eleven months prior the attack on the elementary school, Iraq had embarked on a project to extend the range of the Russian-made SCUD-B missiles in their inventory. This program had reached fruition on August 3, 1988, a date that has become immortalized in the history of the Iraqi Al Hussein Missile Force.

It was the eve of the feast of Bayram, one of the holiest days of the Muslim calendar, honoring the Prophet Ibrahim and his willingness to sacrifice his son, Ishmael, to Allah. Dr. Amer Sa’adi, a suave, German- and English-educated engineer who served as the deputy director of the newly created Military Industrialization Committee, or MIC, sat in his office on the seventh floor of the multi-story office building on Palestine Street, in downtown Baghdad, that served as the organization’s headquarters. Outside, the hot summer sun baked the gleaming city nestled along the banks of the Tigris River. Inside, the employees worked in air-conditioned comfort. The times were hectic – Iraq was in its seventh year of a bloody war with neighboring Iran, and the organization Sa’adi helped lead played a central role in developing the weapons and related technologies needed for that struggle.

Complicating matters even more, Sa’adi was at the time overseeing a major organizational restructuring that saw his former employer, the State Organization for Technical Industry, or SOTI, consolidated with other military research and development entities to form what was now known as MIC, in accordance with the newly passed “Law of Military Industrialization”, which had come into effect on August 1. Project reports from a multitude of ongoing initiatives piled up on Sa’adi’s desk, each one demanding his full attention.

But this day found Amer Sa’adi’s singularly focused on events unfolding more than two hundred kilometers to the west. There, in the desert outside the city of Rutba, a single Soviet-made MAZ-543 transporter-erector-launcher, or TEL, belonging to Unit 224, was preparing to conduct a test launch of a new weapon which, if successful, promised to change the nature of the war with Iran.

Born in 1938, Sa’adi came to adulthood during the violent July 14 Revolution of 1958, which saw the British-installed Hashemite King, Faisal II, his family, and his closest political supporters killed at the hands of a band of rebellious Iraqi military officers known as the Free Officer Group. Sa’adi left Iraq for Europe shortly after the revolution, attending university in Munich, where he studied chemistry before moving on to the United Kingdom, where he obtained his Doctorate in physical chemistry from the Battersea College of Technology (known today as the University of Surrey). Through his studies, Sa’adi met his German wife, Helga, a fellow student, and they were married in 1963.

Upon obtaining his PhD, Sa’adi was commissioned in the Iraqi Army. Later, based out of the West German city of Hamburg, he was tasked with studying the armament industries of East Germany, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia, canvassing them for technologies and weaponry that would be of use to the Iraqi military. His marriage to a German, however, alienated him from the nationalist Iraqi officers belonging to the Ba’ath Party who had seized power in a coup in 1968. Sa’adi was forced to leave the army and return to Baghdad, where he took a job as an engineer with SOTI. His competence, however, caught the eye of Saddam Hussein, and by 1974 Sa’adi was reinstalled in the Army, promoted to the rank of Brigadier General and, in a move which brought him no small amount of satisfaction, put in charge of SOTI.

Seated at a desk situated outside Sa’adi’s office was his chief of staff, Colonel Hossam Mohammed Amin al-Yassin. A distant relative of Iraq’s President, Saddam Hussein, Hossam Amin was educated as an engineer while attending University in Belgrade, Yugoslavia. Upon returning to Iraq, Hossam Amin worked on the development of air defense missiles for the Iraqi Air Force. By 1986, Hossam Amin was placed in charge of the Special Technical Team for the Development of Missile Technology, part of the Research and Engineering Applications Bureau (REAB) of SOTI. One of Hossam Amin’s responsibilities was to travel to Brazil to organize the transfer of air-to-air, surface-to-air, and surface-to-surface missile technology.

Hossam Amin’s technology acquisition efforts took place within the context of the Iran-Iraq War which, by 1986 was entering its sixth bloody year. That same year, following a spate of deadly Iranian SCUD missile attacks against Baghdad, the Iraqi government sought to acquire a similar capability to retaliate against the Iranian capital city of Tehran. The geography of the two warring nations, which put Baghdad a little more than 200 kilometers (around 125 miles) from the Iranian border, while Tehran was located some 500 kilometers (around 310 miles) deep into its own territory. The range of the Soviet-produced SCUD-B missile was 300 kilometers (around 186 miles), meaning that the Iranians could—and did—rain missiles down on the Iraqi capital while avoiding similar retaliation from Iraq.

Faced with the Soviets refusal to provide long-range missiles, the Iraqis looked inward, melding Hossam Amin’s research bureau with the Scientific Research and Technical Development Organization (SRTDO), a research arm of the Iraqi Army, to form the an ad hoc entity known as the “Surface to Surface Missile Development Group”, which was tasked with taking the existing SCUD-B missile Iraq as procured from the Soviet Union, and turning it into a weapon with a range of 600 kilometers (370 miles), capable of striking Tehran.

In February 1987, Saddam Hussein promoted his son-in-law, Hussein Kamal al-Majid, to head up the Military Industrial Organization, which oversaw the work of SOTI. Hussein Kamal was a cousin of Saddam Hussein, and as “family” was entrusted while a junior officer with accompanying Saddam Hussein’s wife and daughters on their shopping trips to Paris and London. In 1982, Hussein Kamal helped thwart an assassination attempt of the Iraqi President, an act that brought him closer into the tight circle of trust that surrounded the Iraqi leader.

In 1983 Hussein Kamal married Ragha, Saddam Hussein’s eldest daughter, and was promoted to the rank of Colonel and made Saddam’s personal bodyguard. By 1986 Saddam began grooming Hussein Kamal for a larger role in government. Hussein Kamal was put under the tutorship of Air Force General Amer Rashid al-Ubeidi, a brilliant British educated electrical engineer who oversaw most of the technical acquisition work of SOTI. After a year of being mentored by General Rashid, Saddam further promoted his son-in-law, replacing Amer Rashid as the head of SOTI (Amer Rashid became Hussein Kamal’s deputy.)

While Hussein Kamal assumed the title of Director of SOTI, Amir Sa’adi was demoted to the position of co-deputy, sharing the title with Amer Rashid. As Kamal’s deputy, Amir Sa’adi continued to run the day-to-day activities of the organization. Meanwhile, the ad-hoc “Surface to Surface Missile Development Group” had grown and moved into offices in SOTI’s Palestine Street headquarters. An Air Force engineer, Dr. Ra’ad Jasim Isma’il Al Adhami, was placed in charge of this group, while Hossam Amin was moved over to Sa’adi’s office where, as Chief of Staff, he monitored the group’s progression as it wrestled with the problem of extending the range of the SCUD-B missile. It was in this role that Hossam awaited a phone call from Dr. Ra’ad informing him about whether their efforts had borne fruit.

At its inception the ad-hoc group comprised some 8-10 engineers organized into working groups which covered airframe analysis, aerodynamics, trajectory analysis, guidance and control, engine, launcher, and system coordination. The SRTDO element, led by Dr. Ra’ad Isma’il, represented the scientific resource base for the group, drawing upon the experience, literature and research materials concerning aerodynamics and ballistic characteristics already existent in that organization. The SOTI-RDG team, headed by Hossam Amin, consisted of specialists who understood the capabilities of the material base of Iraq to support a SCUD-B modification program.

The ad hoc group was assisted by technicians from the Technical Battalion of Unit 224, who provided a warehouse within the Technical Battalion facility at Taji as a workspace. The Technical Battalion also provided a training missile (a cut-away variant of the SCUD-B which was disassembled so that requisite measurements could be made), technical schematics of the SCUD-B missile and launcher, and a MAZ-543 launcher for the group to analyze and assess.

The technical planning committee of the ad-hoc group, based upon their initial analysis of the SCUD-B missile and technical literature surveys (with a special emphasis on open-source technical literature concerning the German V-2 missile program of World War II) initially sought to extend the range of the missile using the simplest approach possible—simply reducing the weight of the warhead. Technicians at the Al Qa’ Qa’ State Establishment, a high-explosive manufacturing complex located some 65 kilometers (40 miles) south of Baghdad, removed the normal 800-kilogram (1,760 pound) charge from a standard SCUD-B warhead, and replaced it with a reduced charge weighing 250 kilograms, or 550 pounds.

On February 11, 1987, the ad-hoc group (by this time having grown to about 15 personnel) conducted its first test flight test, launching a standard SCUD-B missile, upon which was mounted the reduced warhead, from Western Iraq, in the vicinity of a pipeline communications facility known as Kilometer 160, towards the south of Iraq. The test was a failure, with the engine shutting off approximately 30 seconds into its flight, causing the missile to fall to the ground some 25 kilometers (16 miles) from the launch position.

Following the test launch, the ad hoc group met to assess the reasons for the failure. There was widespread consensus that the failure was due to an “instability regime” suffered by the missile due to the decrease in warhead mass—basically the missile was inherently unstable and “wobbled” itself to death. The guidance and control specialists on the team, however, believed that there was a failure in the guidance and control system due to the higher initial velocity achieved by the lighter missile.

While technically the guidance and control argument made the most sense, Dr. Ra’ad Ismail was concerned about conducting any modification of the actual guidance and control devices, as it would represent a complex and timely undertaking. Instead, the decision was made to modify the airframe of the missile to retain the original center of gravity, thereby eliminating the “instability regime”. This was accomplished by extending the capacity of the oxidizer and fuel tanks, thereby increasing the missile mass.

According to the group’s calculations, the missile would have to be extended by approximately 44 centimeters, or 17 inches. The additional fuel and oxidizer carried by the modified missile resulted in an additional six seconds of engine burn time. While the increase in oxidizer and fuel would initially serve to shift the center of gravity of the missile backwards, the ad hoc group felt that the additional burn time would compensate for this—as the fuel was consumed, the additional mass of the extension itself would cause the center of gravity to eventually move forward far enough to compensate for the lighter warhead.

Once the theoretical question of airframe instability resulting from warhead mass reduction had been worked out on paper, the ad-hoc group moved to the task of airframe extension. There were several practical problems facing the group concerning the actual mechanics of conversion. Unit 224 had provided two SCUD-B missiles for use by the group for prototype development. However, at that time in Iraq, there was no establishment that specialized in the cutting and welding of stainless steel. The group enlisted the assistance of the Daura Petroleum Refinery, near Baghdad, for the provision of a pipe cutting machine for the circular cutting of the SCUD-B airframe. The two SCUD-B missiles were cut in this fashion based upon pre-calculated lengths determined by the additional fuel and oxidizer requirements.

Two non-commissioned officers from the Iraqi air force that had experience in welding aircraft were brought in to reassemble the cannibalized missile airframes into a single lengthened missile using hand-held argon welding devices. Additional personnel from Unit 224 were brought in to assist in airframe alignment following the extension work. Alignment was accomplished using theodolite devices and fine wire string, with pre-alignment reference points on the missile being compared with the post-extension results. All in all, it took 15-20 days to complete the modification process. By this time, the ad-hoc group had grown to approximately 30 persons.

The ad hoc group was also concerned about technical problems that might arise due to the increased engine burn time. However, the technicians from Unit 224, having been trained by the Soviets at the surface-to-surface missile school in Kazan, knew that the Soviet technical specifications for the SCUD-B engine provided a performance guarantee of a 100-second burn time, well above the expected 68 second burn time for the extended SCUD-B. At the same time, engineers and specialists from Unit 224 were modifying the launch arm of a MAZ-543 launcher, lengthening the arm, and repositioning the travel-locks to account for the new location of the hard points on the lengthened missile where the travel locks would press down on.

On April 21, 1987, the ad-hoc group conducted a flight test of the extended-range SCUD-B prototype. This test was carried out with the assistance of the 3rd Battalion, Unit 224, utilizing the MAZ-543 with the modified launch arm, launching from an area in the vicinity of Kilometer 160 south towards the city of Nasiriyah. This test was also a failure, repeating the 30 second engine shut-off phenomena and again falling some 25 kilometers (16 miles) away from the test launch site.

After this second consecutive failure, the guidance and control specialists won out. Their analysis showed that the failure could be traced to the accelerometer, which measured the acceleration of the missile. The timing impulses for the standard SCUD-B missile were based upon the acceleration achieved by a normal, unmodified missile. As a result, a blocking signal would be sent from the accelerometer to the timing unit at the 31 second point to initiate engine shut-down (normal engine shut-down for the SCUD-B missile occurred at 62 seconds, or two cycles of the timing gear.) With the higher initial velocities achieved by the lighter missile, however, the accelerometer caused the impulse gear of the accelerometer to move faster than the blocking cam of the timing unit, allowing the engine shut-down signal to be sent earlier, at the 30 second point.

After the failure of the first prototype missile in February, the guidance and control team of the ad-hoc group took apart an accelerometer to measure the number of impulses required to achieve specific ranges. Based upon this knowledge, the group was able to modify the timing cam of the timing unit to provide proper blocking of the engine shut-down signal. This modification was accomplished by simply filing down the cut area of the cam, expanding its length and thus increasing its time span factor. Precise results were obtained through gradual filings, with the resultant modification being tested on the independent test vehicle of the Unit 224 Technical Battalion; repeat tests were conducted as required until the desired time gap was achieved.

Using this modification, a third prototype test missile was prepared and launched on April 28, 1987, again by the 3rd Battalion, Unit 224, from the vicinity of Kilometer 160. This test of the reduced warhead and subsequent modifications to the timing unit was a success, with the missile reaching a range of 450 kilometers (280 miles).

During these tests Unit 224 provided additional support in the form of 60-70 soldiers who were used as so-called “scouts” whose job it was to locate the impact area of the missile warhead. The soldiers positioned themselves along the down-range axis of a 30 x 20-kilometer (18 x 12 mile) rectangle grid which was overlaid on the desired target impact area. Two survey vehicles, one on each side of the grid, would provide the precise coordinates of the impact point. Helicopters were also used to assist in impact location, as well as for support purposes.

Using the insights gained from the first three prototype flight tests, the ad-hoc group prepared a fourth prototype extended range missile, this one designed for a range of 600-650 kilometers (375-400 miles.) The preparation of the fourth prototype saw the ad hoc group begin to coalesce into more formal task-specific sub-groups. One dealt with warhead modification. During the first three flight tests, the Iraqis noticed some discoloration on the warhead’s outer shell which was representative of heat transfer between the inner and outer shell of the warhead. This was interpreted as a bad sign, since the ad hoc group anticipated that the warhead would experience considerable additional exposure to heat due to the higher speeds expected during its lengthened flight. To overcome this problem, the ad-hoc group developed a canister configuration for the warhead. As they had done for the first three missiles, the basic SCUD-B warhead was emptied of its explosive charge utilizing high pressure steam. A separate metal canister was then filled with the reduced explosive charge and bolted into the now-empty warhead.

For the test of April 20, 1987, the Iraqis had extended the length of the missile airframe by 44 centimeters, or 17 inches. For the full extended prototype, the total extension required was 1.32 meters, or 51 inches. In addition to the mechanical aspects (i.e., cutting, fixing, and welding), the ad-hoc group had to develop a precise means of aligning the missile to prevent any excessive torque which would otherwise result. This was achieved by simply modifying the system used for the second test. In addition, the cables which sent signals from the guidance and control system to the engine, which were in a raceway on the side of the missile, had to be extended. The wires were carefully marked with identification tape and then cut, and a 44-centimeter (17 inch) length of cable from a cannibalized missile grafted on.

To accomplish the longer engine burning times needed for the modified SCUD-B missile, the ad-hoc group eliminated the “velocity disk” of the accelerometer which would normally complement the modified timing gear to block engine shut-down signals, thus extending the burn time of the SCUD-B engine by 20 seconds, to 82 seconds. This was accomplished by simply cutting the wire which provided the signal to the “velocity disk”, as opposed to disrupting the stepper motor used to drive the timing gear. The timing unit was likewise modified by altering two cams, one to facilitate the additional 22-seconds of burn time, and the other to delay warhead arming until the 82-second mark. Likewise, the self-destruct mechanism of the missile warhead, designed to be activated after 67-seconds, was disabled to account for the longer burn time.

The ad hoc group remained concerned about the possibility of an instability regime due to a shifting center of gravity on the new extended-range missile. To compensate for this, group increased the area of the missile fins by bolting on an extension. The goal was to shift the center of pressure backwards in keeping with the original parameters of the SCUD-B missile by minimizing the torque on the extended airframe (too much torque resulted in the airframe corkscrewing in the ascent and decent, causing the missile to disintegrate and adversely effecting missile accuracy).

Except for the warhead modifications, all work on the fourth prototype missile was carried out at the ad-hoc group’s warehouse facility in Taji. By the end of July 1987, the ad-hoc group had grown to some 45-50 people, not including the operational support being provided by Unit 224. A total of four extended-length test missiles were assembled by the ad hoc group. On 3 August 1987 the first of these extended missiles was flight tested. The 2nd Battalion of Unit 224 was given the honor of carrying out the test.

Their work was overseen by the commander of Unit 224, Brigadier General Hazem Ayoubi. The missile was successfully launched from the vicinity of Rutba (the longer intended range of the test missile made launching from the Kilometer 160 test range impractical). As the missile rose into the sky, General Ayoubi and the men of the 2nd Battalion held their breath. At the 30 second mark, the missile still functioned, disappearing into the sky. Ayoubi congratulated his men—their mission had been accomplished.

Down range, near the southern Iraqi village of Bussaya, the observers from Unit 224 scanned the horizon, looking for the arrival of the missile. When it arrived, however, something was wrong—the missile was wobbling and looked as if it had broken into two pieces. The missile pancaked onto the ground, the warhead failing to explode. The technicians from the ad hoc group were flown to the impact zone in a helicopter and examined the debris. The extended fins had broken off, and the missile had broken apart along the guidance section, between the warhead and the oxidizer tank.

Dr. Ra’ad Ismail conferred with his fellow engineers, before reaching a conclusion: the missile had flown to its desired range of 650 kilometers (400 miles), long enough to reach the Iranian capital of Teheran. The ad hoc group determined that the basic design of the extended missile was validated, and that the missile’s warhead would successfully detonate upon impact. Dr. Ra’ad used an HF radio to contact the team members in Rutbah, notifying them of the positive result. This message was passed on to Hossam Amin, who in turn briefed Amer Sa’adi.

The next morning, Amer Sa’adi, accompanied by Dr. Ra’ad Ismail, briefed the test results to Saddam Hussein. In honor of the fact that the test took place on the eve of Bayram, the group recommended that the new missile be named “the Missile of Arafat”. Saddam, however, directed that the missile be called the Al Hussein.

Within a week of the successful flight test of the Al Hussein missile, the newly formed Ministry of Industry and Military Industrialization, or MIMI, issued an order which disbanded the State Organization for Technical Industry, or SOTI, and reassigning its Research and Development Group to the newly formed Bureau of Research and Engineering Applications, under the direction of Hossam Amin, where, in early September 1987, they joined with the ad-hoc Surface to Surface Missile Development Group to create a new entity, known as Project 144, under the direction of Ra’ad Ismail. Project 144 took over responsibility for the Al-Hussein manufacturing program, assuming control over the original workshops associated with the efforts of the ad-hoc group. Project 144 established its headquarters and working spaces adjacent to the Unit 224 Technical Battalion, located in the Taji Military complex north of Baghdad.

Based upon the success of the August 3 flight test, the initial technical requirements for manufacturing the Al Hussein missile were set forth by the ad-hoc group based upon the five areas of modification required for the extended-range missile. These requirements were organized in respect to the specific technical problems being addressed (i.e., warhead mass reduction, fuel and oxidizer tank extension, timer modifications, and increased engine burn times.) When Project 144 took over responsibility for the Al Hussein program in September 1987, these efforts were consolidated into five numbered workshops.

Workshop 144/1 was responsible for reducing the mass of the SCUD-B warhead for use on the Al Hussein, and had the responsibility for making the required physical modifications to the actual warhead casing and, in coordination with the warhead filling unit at the Al Qa’ Qa’ General Establishment, located south of Baghdad, removing the original high explosive charge by means of a high-pressure steam unit and refilling the empty case with a reduced charge of Iraqi-produced high explosive.

Workshop 144/2 was responsible for modifying the SCUD-B fuel and oxidizer tanks to the extended configurations required for the Al Hussein. The extension of the SCUD-B fuel and oxidizer tanks was a more complex problem than warhead mass reduction. The engineers of Workshop 144/2 had to make calculations involving fuel consumption rates and the related increase in fuel and oxidizer volume to provide a theoretical model which determined the necessary extension in length required. The engineers also had to ensure the proper physical configuration of the extended airframe of the Al Hussein in keeping with the principles of aerodynamics (i.e., shifting center of gravity and increased airframe stress.) The actual physical task of manufacturing the extensions was the least of their problems.

Workshop 144/2 started with a single prototype modification line. Initially, Workshop 144/2 could produce one Al Hussein every three days. After the successful August 3 test, a second production line was installed, which began producing missiles in mid-September; the rate of production increased to one missile every two days. In December 1987, Workshop144/2 further expanded its modification lines from two to four, and Workshop was able to produce one missile a day. From the inception of the Al Hussein modification program until December 1987, Project 144 used 175 SCUD-B missiles to produce 125 Al Hussein missiles. Fifty SCUD-B missiles were cannibalized and thus made inoperable because of this effort.

Workshop 144/3 assumed the responsibility of the Missile Technology Development technical team that had been resident within SOTI to more effectively manage the work of the engineers involved in the Al Hussein project and to maximize manpower resources of Project 144. Workshop 144/3 was responsible for the modification and development of short-range missiles, as well as tendering support and technical consultations to the armed forces.

Workshop 144/4 was assigned the task of modifying the timer cam of the timer unit and gear disc of the gyroscopic accelerometer of the SCUD-B guidance and control system, as well as modifying the electrical harness of the missile (i.e., the cable raceway) and the SCUD-B’s self-destruct device.

Even though the August 3, 1987, missile test was a successful demonstration of the potential for the Al Hussein missile to reach the Iranian capital of Tehran, the fact is that the missile pancaked on the surface, resulting in the warhead not detonating; there remained considerable work to be done before the concept could be declared operational and delivered to the Iraqi military for use in combat.

In this regard, Project 144 constructed seven more Al Hussein prototype missiles, three of which were set aside for the purpose of conducting verification tests designed to repeat the success of the August 3 test launch. These missiles were launched on September 28, 1987, from three modified MAZ-543 TELs operating in the vicinity of Ruwayshid (a military airfield located in the so-called “Ruwayshid strip”, which at the time was under the jurisdiction of Iraq, but which later was returned to Jordanian control). The purpose of these launches was to verify the “success” of the August 3 launch. All three launches were of missiles equipped with enlarged fins and utilizing canister warheads and were all deemed successful. Success criteria, however, was rather crude, based solely upon the missile travelling the desired distance of 600-650 kilometers; all the missiles continued to pancake on impact.

By early October several more missiles had been manufactured, and the Director of Project 144 selected two of these aside for additional test firings. On October 5, and again on October 14, two more launches of Al Hussein prototypes took place, this time from between Rutba and Al Qaim, south towards Nasiriyah. Like the seven missiles launched in September, these tests were intended to validate the Al-Hussein missile design and prior test results and were likewise considered to be successful solely on range criterion. As with the previous tests, the Iraqis did not make any use of trajectory tracking radars, instead relying on the so-called “scout” method of observing impact that had been used since the initial flight tests of the prototype missile back in April 1987.

The October 14 test coincided with the Iranian missile strike that hit the elementary school in Baghdad. Revenge was now in the air, and the engineers at Project 144 were under considerable pressure to deliver to the Iraqi Army a missile capable of reaching Tehran, thereby allowing similar destruction to be met out on the Iranian people.

On November 18, 1987, an additional two Al Hussein missiles were test fired to conduct validation of the missile batches produced through early November, again from positions between Rutbah and Al Qaim towards Nasiriyah. However, this time personnel observing missile re-entry from impact area noticed that the missiles were coming to earth in a near horizontal position and travelling at very slow speeds. Likewise, while the range of the missile was within standards, its lateral accuracy was extremely poor. The fin extensions had burned or broken off, leading some engineers to speculate that the enlarged fins were in fact hindering the flight of the missile.

Ra’ad Ismail decided to conduct a comparison test launch between an Al Hussein with fin extensions and an Al Hussein with unmodified fins. This final Al Hussein validation test took place on December 28, 1987, when two of the Al-Hussein prototypes were fired, again from the vicinity of Rutbah in a southerly direction, towards Nasiriyah. On this occasion, the missile with fin extensions was again observed by test “scouts” as falling to earth in a slow, horizontal fashion, exhibiting poor accuracy. The Al Hussein with unmodified fins fell at much higher speeds, with the airframe pointing downwards and impacting with a relatively much tighter CEP. From that moment on, the leadership of Project 144 decided that all Al Hussein missiles would be produced with the original, unmodified fins.

Likewise, the post-flight examination of the Al Hussein missile debris revealed that the warhead canister was breaking loose in flight, moving backwards into the guidance and control section, thereby impacting not only the center of gravity of the missile, but also preventing it from detonating on impact. Ra’ad Ismail made the decision to only utilize warheads which had been filled with a reduced high explosive charge directly; there would be no more use of the canister concept.

These decisions did not in any way impact on the overall modification process of the Al Hussein, as both the fin extensions and warhead filling were conducted on a case-by-case basis prior to each test launch. After the December 28, 1987, tests, all warheads for the Al Hussein would be filled with a 300-kilogram high explosive charge, and no missiles would be fitted with fin extensions. This was the design variant which was delivered to the Iraqi Army in February 1988 for use against Iran.

The War of the Cities

Since declaring the success of the Al Hussein missile in August 1987, the Iraqi public had not seen evidence of this “miracle” weapon, even though Iranian missile attacks against Baghdad continued. Project 144 had been directed by the Iraqi leadership to produce enough missiles to enable a sustained campaign against Teheran to take place. However, at the start of September 1987, Iraq had only 360 SCUD-B missiles remaining in its inventory. The Iraqi High Command had determined that it required 110 operational Al-Hussein’s to be completed and delivered to the Iraqi Army before it could begin a campaign against Iranian cities. To sustain such a campaign, however, many more Al Hussein’s had to be available.

Iraq needed more missiles.

By this time, however, the Votkinsk SCUD-B production line had been shut down. Moreover, the Soviet Army was preparing to withdraw from Afghanistan. In preparation for this, the Soviets transferred around 2,000 SCUD-B missiles to the Afghan Army so that it could continue to resist the Mujahadeen once the Soviets were gone. Most of these stocks came from Soviet depots containing SCUD-B missiles that had been withdrawn from active service. In short, there were not any “spare” SCUD-B missiles available for delivery to Iraq.

In September of 1987, however, the Soviets reached out to Iraq with the news that it had “found” a total of 118 SCUD-B missiles that could be made available to delivery to Iraq. The Iraqis dispatched a team to Moscow, which concluded two separate contracts with the Soviet Union for the delivery of 118 additional SCUD-B missiles (one contract for 30 missiles, one for 88). In mid-January 1988 the Soviet merchant ship “Bakouriani” arrived in the Saudi port city of Khodayma, where it delivered 36 SCUD-B missiles, which were then loaded onto trucks and driven to Iraq. A separate Soviet merchant ship, the “Ivan Moskolenko”, delivered the fuel, oxidizer, and warheads. The country designator for arms shipment to Iraq was “808”; interestingly, the shipping documents for the missiles and warheads delivered through Khodayma all bore the country code “240”—Libya.

In late January-early February 1988 two more Soviet merchant ships arrived in the Persian Gulf, this time docking at the Kuwaiti port city of Sha’aybah. Between them, the “Ivan Shipetkov” and “Ivan Moskelenko” (making a return visit) delivered 82 missiles, together with warheads and corresponding fuel and oxidizer. These missiles arrived at the Unit 224 Missile Storage Unit between February 14-20, 1988, where they were logged in before being transferred to Project 144 for modification into Al Hussein missiles.

The need to get to 110 missiles was urgent. Throughout December 1987 Project 144 diverted all its resources to the missile modification effort. For two months the engineers and technicians of Project 144 worked day and night to modify missiles; in many cases, especially during the later stage of this effort, missiles were delivered to the Iraqi Army unpainted.

Project 144 was also tasked with developing a firing table that could be used by Unit 224 for targeting purposes. Project 144 had no experience in developing firing tables, nor did the officers of Unit 224 have any knowledge of how firing tables were developed in the Soviet Union for the SCUD-B missile. For the Al Hussein missile, the Iraqis decided to by-pass the “lower” gear (the time compensation gear), which provided compensating pulses at a rate of 12.5 pulses per second in relation to the “upper” gear, or velocity gear, which operated based upon actual impulses imputed at the time of launch. The Iraqi engineers at workshop 144/4 in Taji determined that for the Al Hussein missile the compensating pulse was not needed, and that in fact such compensating pulses would have a negative impact on the accuracy of the Al Hussein. The Iraqis disabled the “lower” gear by cutting off the external power supply to the stepper motor used for the time compensation gear.

A flight test was conducted on February 24, 1988, to check the results of this modification. The Iraqi Army was, at that time, in final preparation for the initiation of a campaign of ballistic missile strikes against Teheran and wanted these strikes to be as accurate as possible. Two missiles—a SCUD-B and an Al Hussein—both having been modified by having power cut to the “lower” gear, were fired from the vicinity of Ar Rutbah towards Nukhaub. Both missiles were fired to a range of 280-290 kilometers to have a comparative means of discerning the accuracy of the pulses programmed into each missile.

The test verified prior Iraqi calculations concerning the variation in impulse input (approximately 9,500 for the SCUD-B missile to travel 280-290 kilometers versus 9,800 for the Al Hussein.) Based upon the results of this experiment, the Iraqis were able to create an Al Hussein firing table which provided the Iraqi Army with ten distinct firing options, ranging between 580 and 650 kilometers from the intended target.

Iraq was ready to begin the campaign of revenge it had promised back in October 1987, when the Iranian Hawsong-5 missile had struck the school in Baghdad, since renamed “Balat al-Shuhada”, or the “the Path of the Martyrs”. On the morning of February 29, 1988, Iran fired three Hawsong-5 missiles into Baghdad, killing an undisclosed number of civilians. Iraq responded by firing five Al-Hussein missiles against the city of Teheran, killing 16 civilians. This was the first operational use of the Al Hussein missile.

The “War of the Cities” had begun.

Iraq had the ideal man in place as the commander of Unit 224 to carry out the coming campaign. Throughout the Iran-Iraq War, Hazem Abdul-Razzaq Shihab Ayoubi had risen through the ranks, including firing battery commander (i.e., in command of a MAZ-543 TEL.) He attended Staff College where, upon graduation, he returned to Unit 224 to command the Missile Maintenance Unit. In May 1987 Staff Colonel Ayoubi was promoted to Brigadier General and put in command of Unit 224.

Hazem Ayoubi oversaw the testing of the Al Hussein missile and made the preparations necessary for Unit 224 to transition from being a SCUD-B Brigade to one capable of firing the longer-range Al Hussein. By this time Unit 224 had transitioned from being a battle support organization into a strategic asset, operating under the direct orders of the President of Iraq, Saddam Hussein. By early 1988, Iraq was at its breaking point. The stalemate on the battlefield needed to be broken, and a key aspect of this was to break the Iranian people’s will to continue the fight. This was the role given Brigadier Hazem Ayoubi and the men of Unit 224. It was a job he had, literally, been preparing for his entire professional life.

Up until the “War of the Cities” was initiated using the new Al Hussein missiles, Unit 224 operated along the lines of how they had been instructed by the Soviets in Kazan—a MAZ-543 launcher would move to its launch site, where it would be met by an empty SCUD-B missile airframe, a warhead, guidance and control devices, and fuel and oxidizer vehicles. The guidance and control devices would be installed and programed for the desired range to target, and then the warhead mounted. The missile would then be loaded onto the MAZ-543, after which it would be loaded with fuel and oxidizer. Once this was completed, the final adjustments regarding the azimuth of launch would be made while all other vehicles exited the launch site. Once all preparations were completed, the order for launch would be given. The launch would be either initiated by an officer seated inside the launch control compartment of the MAZ-543, or by an officer set up in a safe position, connected to the launcher by an umbilical connected to a launch button. From start to launch, the time needed to prepare a SCUD-B for launch usually took about an hour.

The modifications to the Al Hussein missile, in which the fuel and oxidizer tanks were both extended, requiring more fuel than the original SCUD-B fueling apparatus could deliver, meant that the Iraqis had to modify their launch procedures. Instead of all the support equipment coming to the launch site, the Iraqis established a fueling and arming station removed from the planned launch site. The MAZ-543 would drive to this location, where a missile was waiting, already fueled, mated with a warhead, and with the guidance and control devices set for the desired target. The missile would be loaded onto the MAZ-543, which would then drive to the launch site. There, the only thing that needed to be done was to raise the missile, adjust the azimuth, and fire. In this way, the actual time spent at the launch site was under ten minutes. Brigadier Ayoubi developed these new tactics with his officers and made them standard operating procedure.

Iraq started the “War of the Cities” with 111 Al Hussein missiles on hand. During the “War of the Cities” the Workshop 144/2 missile modification lines were expanded from four to six. In addition to expanding production capacity, the Iraqis were able to increase modification efficiency. Initially, Project 144 was able to produce a single Al Hussein missile by cannibalizing SCUD-B missiles at a ratio of 3:2 (three SCUD-B missiles were used to manufacture two Al Hussein missiles). Project 144 modified missiles at a ratio of 3:2 up until the last quarter of 1987.

Starting in December 1987, the engineers of Project 144 developed a technique for the conversion of SCUD-B missiles to Al Hussein at a ratio of 4:3; this rate was maintained through the end of 1988. In this manner, Iraq was able to convert 208 SCUD-B missiles into 126 Al Hussein missiles during the “War of the Cities”, providing a total inventory available of 237 through the duration of the campaign (an additional 26 Al Hussein missiles were readied for production through the cannibalization of 36 SCUD-B missiles during the production surge that took place during the “War of the Cities”, but were not assembled until late 1989, after the process for 1:1 conversion was developed).

The goal of the “War of the Cities” was not the outright defeat of Iran, but rather to pound the Iranians into submission when it came to attacks on Iraqi civilian targets. If Iran could be compelled to stop striking the Iraqi people, then Saddam would be able to secure the home front and use it as the foundation for a final offensive to break the Iranian ability to continue the war, thereby forcing the Iranian leadership to accept the terms of United Nations Security Council resolution 598, which had been passed back in July 1987. Iraq had agreed to the ceasefire. Iran, however, had rejected it, loath to make peace with Iraq so long as Saddam Hussein remained in power.

The initial Al Hussein attacks caught Iran completely by surprise. The first launches, involving three Al Hussein missiles, took place at approximately 6 pm, followed by two more Al Hussein launches at 8 pm. All five missiles targeted Tehran. One of these missiles struck a hospital, killing 16 civilians. The Iranians, unaccustomed to being hit by missiles, at first blamed the attacks of the Iraqi Air Force. Iraq, however, confirmed the attacks, announcing that every Iranian city was now vulnerable to attack from Iraq’s “gigantic missile force.”[10] Over the course of the next 24 hours, Iraq made good on its claim, launching a total of 17 Al Hussein missiles against Tehran.

Iran, for its part, did not hold back, firing salvos of Hawsong-5 missiles against Baghdad and other Iraqi cities. The North Korean missiles, however, were significantly less accurate than the Soviet SCUD-B, and most of the dozens of missiles fired by Iran landed in rural areas surrounding Baghdad. The same, however, could not be said of the Al Hussein, which repeatedly struck Tehran with deadly effect. In the first 12 days of the “War of the Cities”, the Iraqi missile attacks killed more than 200 Iranian civilians and wounded several hundred more.

Iraq made a furtive first effort at ending the “War of the Cities”. Under pressure from the United States, Great Britain, and France to suspend its missile attacks on Iran while the United Nations Security Council met to discuss the imposition of economic sanctions on Iran for failing to agree to the Council’s resolution calling for a ceasefire, Saddam Hussein convened a meeting of the Revolutionary Command Council, where the decision was made regarding the cease fire offer.

This offer was communicated to the ambassadors of the five permanent members of the Security Council on March 10. That evening, after attacking Tehran with two Al Hussein missiles, the Iraqi government read a statement over Baghdad Radio that it would halt its missile attacks against Iranian cities at midnight that night and would continue to hold its fire if Iran refrained from attacking Iraqi cities. The Iraqi broadcast had made the ceasefire conditional on Iraq being the last party to fire missiles at the other. “As Iran was the party that initiated the ‘War of the Cities’,” the statement declared, “the last bombardment operation will be by Iraq before it implements the halt.”[11]

Iran responded to the Iraqi offer with a radio message of its own, claiming that it would respect the ceasefire if Iraq, in turn, refrained from attacking Iranian cities. Shortly after the radio broadcast, however, two Iranian Hawsong-5 missiles were fired at Baghdad, prompting an immediate Iraqi retaliatory strike against Tehran using a single Al Hussein. Iraq continued its attacks the next morning, firing two Al Hussein missiles at Tehran. The shaky truce held for two more days, ending when Iraq fired a single Al Hussein at Tehran in retaliation for a deadly Iranian artillery attack near Hallabja, along the Iran-Iraq border in northern Iraq. “If the Iranian regime continues its aggression,” an Iraqi communique announced, “then our retaliation will continue with all-out strength.”[12]

Iran and Iraq traded missile strikes for the next week. Not even a major holiday could trigger a cessation in the attacks. March 21 marked the Iranian New Year, or NowRuz, was one of the biggest celebrations in Iran. Preparations for NowRuz begin weeks in advance, with homes meticulously cleansed to wash away evil spirits, and new clothes, either hand-made or store bought, procured for the festivities, In the days before NowRuz, bonfires are traditionally lit, and children wearing costumes jump over them in preparation for the new year to come.

Iraq fired two Al Hussein’s at Tehran that day. The first missile struck just after midnight, slamming into the Tehran’s Jamaran district, home to Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The second missile attack occurred shortly after 4 pm, causing a city full of holiday celebrants to pause what they were doing and look up to the sky, where they were able to visually track the missile as it dove into the packed southern suburbs of the city, “exploding with a long, double kaboom.”

The two explosions broke the windows of hundreds of structures in the two neighborhoods that were struck. Neighborhood committees, by this time well accustomed to the realities that accompany a missile strike, made their way to the stricken structures, where they hung plastic sheeting over the now-empty windows to ward off the chill of the March night. Hospitals filled with the newly wounded were packed with “grim-faced relatives” who packed the halls. Even during the NowRuz celebration, the city looked as if it were under siege, with sandbags piled up at the entrances to government buildings and businesses, and freshly constructed reinforced concrete air raid shelters popping up near bus stops and in Tehran’s densely packed neighborhoods.[13]

A week later, on March 28, Iraq initiated an unofficial ceasefire to accommodate a three-day visit of Turkish Prime Minister Ozal to Baghdad, which began on April 1. But the ceasefire, like the others before, did not hold. According to Iraq, Iran fired a missile at the southern Iraqi port city of Umm Qasr, striking a school, killing three students and wounding 41 others. Iraq responded by renewing its missile assault on Tehran.

Lulled into a false sense of complicity brought on by the week-long ceasefire, the citizens of Tehran were once again shocked to hear the “earsplitting crack” of an Al Hussein missile breaking the speed of sound in the sky over their heads, and to look up and see the path of the incoming missile marked by the burning of residual fuel in the missile’s tanks, watching helplessly as the missile fell to earth, producing “a loud explosion” that sent up “an ominous cloud of brown dust.” Police, fire trucks and ambulances rushed to the scene. That night, the citizens of Tehran once again began fleeing to safer locations.[14]

All in all, Iraq fired 189 Al Husseins into Iran during the 52 days that the “War of the Cities” unfolded; 118 of these were targeted at Tehran. Eighty-six missiles landed in populated areas, killing 422 civilians, and injuring another 1,579 injured (approximately 20 military personnel were also killed, and some 75 wounded by these missile strikes.) Of the 118 Al Hussein missiles fired at Tehran, 23 exploded in the air over the city. Of the 95 remaining missiles, seven impacted on military or industrial facilities, two landed in rural areas, and 84 struck populated areas of the city; two missiles failed to detonate.[15]

Statistics alone, however, fail to capture the visceral reality of the Al Hussein missile and its impact on Iranian civilian morale. By February 1988, Iran and Iraq had been at war for seven and a half years. While the Iranians had been successful in expelling Iraqi forces from the territory of Iran and even pushing the frontlines across the border into Iraq, these victories had come at an extremely high cost. The nation had been bled dry, and the annual mobilizations were not generating the number of recruits necessary to sustain the manpower-intensive offensive operations of past years. The war had become a stalemate, with the strategic momentum shifting back to Iraq, which was undertaking a massive rearmament and reorganization campaign focused on offensive operations to eject Iran from its soil.

The Iraqis had problems of their own. Like Iran, the war had taken its toll on the Iraqi population. Saddam Hussein, however, governed over a regime where tribal loyalty served as the foundation of his regime’s strength. This was especially true among the Sunni tribes. Saddam was able to secure the loyalty of these tribes by placing their sons in elite military units, service in which served as a conduit for largesse in the form of higher pay and benefits such as housing and cars. While some sacrifice was expected, Saddam could not be seen as squandering a tribe’s lifeblood through repeated battlefield misadventures.

The morale of the average Iraqi citizen was a critical factor in the psychology of victory Saddam was seeking to infuse. Iran’s incessant bombardment of Baghdad and other major Iraqi cities, such as Mosul, Kirkuk, Basra, and even Saddam’s hometown of Tikrit, were an ever-present reminder that the Iraqi government was failing in its mission of shielding the Iraqi people from harm. The Al Hussein missile was never meant as a classic strategic weapon capable of destroying Iranian physical infrastructure. Its target was the psyche of both the Iranian and Iraqi people—to bring the war home for the citizens of Tehran, and to provide the Iraqi people with the knowledge that their government was exacting revenge for the Iranian missiles that rained down on their heads.

The incessant Iraqi attacks had worn down both the Iranian people, their government, and the Iranian military’s capacity for retaliation. After firing some 70 Hawsong-5 missiles at Baghdad and other Iraqi cities, the Iranian missile inventory was depleted. In Tehran, an estimated 25% of the city’s 10 million occupants had fled, with millions more opting to spend the night away, commuting to work from the ski lodges and rental homes in the nearby Elburz mountains, or locations as far away as the Caspian shore. Even the Iranian parliamentary elections were impacted, with two Al Hussein’s striking the city as the polls were open on April 8. When the Iraqi Army launched a surprise attack that succeeded in recapturing the strategically important Al Fao peninsula, the Iranian government had no choice but to bring the bombardment of its cities to an end accepting the Iraqi conditions that Iraqi towns and cities were off limits to Iranian attacks. This was the beginning of a long string of battlefield reversals which left the Iranian leadership with no choice but to finally accept the terms of Security Council Resolution 598.

The Iran-Iraq War was over. While credit for the Iraqi “victory” could rightfully be given to any number of officers, units, and organizations, the role played by Project 144 in creating the Al Hussein missile, and by Unit 224 in carrying out the most intensive missile campaign in history, were singled out by Saddam Hussein for praise and reward. Both Ra’ad Ismail, the Director of Project 144, and Major General Hazem Ayoubi, the commander of Unit 224, were awarded the prestigious Wisam al-Rafidain (Order of the Two Rivers, named for the two great rivers of Iraq, the Tigris and Euphrates.) Other awards were lavished on the men who served in both organizations.

The Al Hussein missile had come of age.

[1] A note on sources: Unless otherwise sourced, all information in this chapter is derived from interviews of Iraqi officers and engineers involved with the Iraqi Al Hussein missile program, and notes taken from the examination of Soviet procurement documents related to the Iraqi acquisition of the SCUD-B missile.

[2] Anatoly Zak, “The Rest of the Rocket Scientists”, Smithsonian Magazine, September 2003.

[3] Steven Zaloga, Scud Ballistic Missile and Launch Systems 1955–2005, Bloomsbury Publishing (2013).

[4] Victor Israelyan, Inside the Kremlin During the Yom Kippur War, Pennsylvania State Press, 1995, pp. 111.

[5] “13 Iranian missile men in Syria, training of Scud-B in Damascus”, Iran’s missile uprising, Part 3, November 25, 2015.

[6] “Iran Claims it Hit Baghdad with Missile”, The Los Angeles Times, March 14, 1985.

[7] “New Explosion in Baghdad Increases Doubts About Missile Attacks”, The New York Times, April 5, 1985.

[8] Christopher Dickey, “Iranian Missile Hits Baghdad”, The Washington Post, May 29, 1985.

[9] Charles Wallace, “Iranian Missile Hits Baghdad School; 32 Die”, The Los Angeles Times, October 14, 1987.

[10] Charles Wallace, “Iraq Fires Five Missiles at Tehran After Iranians Strike Baghdad”, The Los Angeles Times, March 1, 1988.

[11] Charles Wallace, “Baghdad Says It’s Ending ‘War of Cities’: But More Missiles Are Fired at Tehran as Truce Deadline Nears”, The Los Angeles Times, March 11, 1988.

[12]Charles Wallace, “‘War of Cities’ Truce Ends as Iraqi Missile Hits Tehran”, The Los Angeles Times, March 14, 1988.

[13] Patrick Tyler, “Damage by Iraqi Missiles Evident in Tehran”, The Washington Post, March 22, 1988.

[14] John Bierman, “A battered city under siege”, Maclean’s, April 18, 1988.

[15] Ali Khaji, “Civilian casualties of Iraqi ballistic missile attack to Tehran, capital of Iran”, Chinese Journal of Traumatology, Volume 15, Issue 3, June 2012, pp. 162-165.

So much detailed information. It must have taken many hours to put together. Reflecting on the Iran-Iraq war it was so sad they were fighting each other. Like World War I there really was no reason for it. I guess you could say that about almost all wars.

Great writing