The Institutionalization of Russophobia in America, Part One: The Analysts

The distortions of reality which underpin virtually all the CIA’s Russia analysis is done deliberately. The CIA is not looking for the truth. Instead, it seeks to drown the truth in a sea of lies.

This is the first of a five-part series of articles on the institutionalization of Russophobia in America. In this article, the role played by intelligence community Russia-specific analysts in transforming their inherent anti-Russian bias into official policy that impacts the national security of the American people is explored, with a special emphasis on the role played by these analysts in promulgating the false narrative of Russian efforts to tip the 2016 Presidential election in favor of Donald Trump.

In the days before President Donald Trump’s historic Alaska Summit with Russian President Vladimir Putin, CIA Director John Ratcliffe turned to his top Russia expert to prepare Trump for this critical meeting. The analyst he chose for this critical task –Julia Gurganus—had served in the CIA for two decades. At the time of her briefings to President Trump was a Senior Executive Manager for the CIA’s Europe and Eurasia Mission Center—the so-called “Russia House”, responsible for bring together the full range of the CIA’s operational, analytic, support, technical, and digital capabilities in a whole-of-Agency approach to providing intelligence support for senior US policy and decision makers—including the President of the United States.

Gurganus was a veteran Russian analyst with more than two decades experience in the CIA. From 2014 through 2017, she served as the National Intelligence Officer (NIO) for Russia and Eurasia—the principal Intelligence Community Russian expert reporting to the Director for National Intelligence, who at that time was James Clapper. Here she played a major role in shaping US policy seeking to use Ukraine as a vector for the destabilization of Russia. In short, Gurganus is one of the principal architects of the policies which led to the Russian-Ukrainian conflict in February 2022.

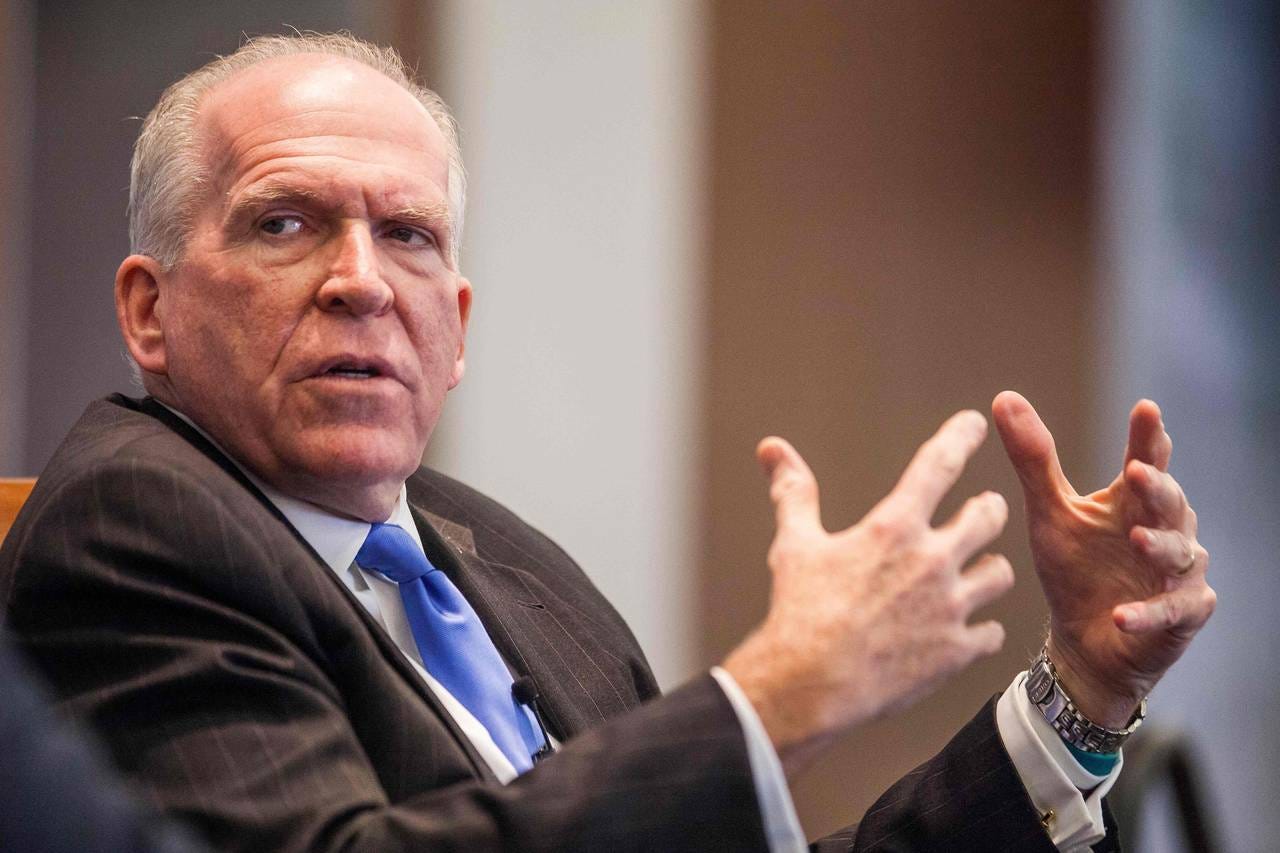

Gurganus also played a leading role overseeing an analytical effort the manipulation and manufacturing of intelligence used to sustain allegations of collusion between then-presidential candidate Donald Trump and the Russian government in the lead up to the 2016 Presidential election. She oversaw the drafting of the 2016 Intelligence Community Assessment (ICA) ordered by President Obama after Trump won the 2016 election which sought to portray Trump as a de facto agent of the Russian government. The 2016 ICA was published on December 30, 2016. At the center of the controversy over the 2016 ICA is the fact that, in sharp deviation from standard practice when producing an ICA of this visibility and importance, the Director of the CIA, John Brennan, instead left the drafting of the ICA in the hands of five CIA analysts, and then rushed its production in order to publish two weeks before President-elect Trump was sworn-in.

Shortly after the 2016 ICA on Russia was published, Gurganus took a sabbatical from her official duties at the CIA, instead serving as a nonresident scholar with the Russia and Eurasia Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Sometime before the spring of 2025 Gurganus returned to the CIA as a manager in the Europe and Eurasia Mission Center. She was in a holding position, pending her assignment to a prestigious analytical position in Europe.

One of the main reasons that Gurganus took her Carnegie sabbatical was to distance her from any potential political fallout over the 2016 ICA. Controversy swirled around the document, with those involved in its production accused of, at worse, fabricating an intelligence-driven hoax designed to undermine Donald Trump’s candidacy in the 2016 Presidential election and, after his victory, to derail his presidency or, at the very least, substandard analytical tradecraft that reeked of politicized intelligence.

When John Ratcliffe took the helm as the Director of the CIA in January 2025, he was aware of the firestorm that was headed his way when it came to President Trump settling score with those involved in what Trump called “the Russia hoax.” For this reason, Ratcliffe opted to get ahead of the curve, ordering the Deputy Director for Analysis, in May 2025, to conduct a “tradecraft review” of the 2016 ICA on Russian Election Interference. This review was published on June 26, 2025.

Most of the high-profile CIA officers that had been involved in the analytical processes involved in the production of the 2017 ICA had already left government service by the time Radcliffe published his tradecraft review. Andrea Kendall-Taylor, a veteran Russian analyst who served as the deputy national intelligence officer for Russia and Eurasia from 2015 to 2018, was hand-picked by then-CIA Director John Brennan to head up an interagency “fusion cell” of analysts from the CIA, NSA, and FBI to investigate the issue of Russian interference in the 2016 Presidential election. Kendall-Taylor recruited Michael van Landingham, a mid-level CIA Russia expert, to serve as the lead analyst for the fusion cell, and later to serve as the drafter of the 2017 ICA. Kendall-Taylor left the CIA in 2018, and van Landingham walked away in 2019.

Ratcliffe’s tradecraft review found fault in what was the 2016 ICA’s “most contentious finding”—that Russian President Vladimir Putin developed “a clear preference” for then-candidate Trump and “aspired to help his chances of victory” in the 2016 Presidential election. This finding was reported with “high confidence”, meaning that it was derived from high-quality information from multiple sources. The reality is that the “aspire” assessment was derived from a single source of information of unknown quality.

But Ratcliffe quickly brushed this finding under the rug, declaring that the tradecraft review “found much of the ICA's tradecraft to be robust and consistent” with Intelligence Community analytical standards. Ratcliffe praised the ICA’s “analytic rigor” citing the 173 separate CIA, NSA, and FBI reports the drafters utilized, along with 74 citations from open sources. “The ICA also demonstrated strong adherence to tradecraft standards through frequent use of attributive language, explicit identification of intelligence gaps, and clear statements of confidence levels,” Ratcliffe’s report noted. “This level of analytic rigor exceeded that of most IC assessments,” Ratcliffe concluded, adding that while the tradecraft review “identified specific procedural and tradecraft issues with the one judgment, these issues should not be interpreted as indicative of broader systemic problems in the IC's analytic processes or standards.”

In short, Ratcliffe declared that there was nothing to see here. In any case, Kendall-Taylor and van Landingham were no longer in government service.

Ratcliffe also took pains to distance the CIA’s senior leadership from any allegations of analytical wrongdoing. Again, he was assisted by the fact that the two most prominent senior CIA personnel involved had, like Taylor-Kendall and van Landingham, both retired. Peter Clement, a senior CIA Russia analyst who served as the Deputy Assistant Director Europe and Eurasia Mission Center during the period covered by the 2016 Presidential election and 2017 ICA publication, retired in 2017. Elizabeth Kimber, a veteran Russia hand from the CIA’s clandestine service, served as the Director of the Europe and Eurasia Mission Center, a job she held until she was promoted as the Deputy Director for Operations in December 2018. Kimber retired from the CIA in October 2022.

Ratcliffe went out of his way to highlight the fact that both Clement and Kimber—the tradecraft review did not mention their names, but rather referred to them as “the two senior leaders of the CIA mission center responsible for Russia”—had opposed including the FBI’s controversial “Steele Dossier” in the 2016 ICA, declaring that “it did not meet even the most basic tradecraft standards.” The tradecraft review also noted that Clement and Kimber “argued jointly against including the ‘aspire’ judgment” in the 2016 ICA, arguing that “it was both weakly supported and unnecessary, given the strength and logic of the paper’s other findings on intent.” Clement and Kimber both warned that including it would only “open up a line of very politicized inquiry.”

Here, Clement and Kimber were correct.

There were two CIA officers who had played a role in the production of the 2016 ICA who were still in employment of the US government at the time Radcliffe conducted his tradecraft review. One, Shelby Pierson, was a senior CIA Russia analyst who served as the lead issue manager for Russia and Ukraine within the Europe and Eurasia Mission Center from 2013-2016. In November 2016, two weeks before President Obama ordered the intelligence community to prepare the 2016 ICA, Pierson was promoted to serve as the National Intelligence Manager for Russia, Europe and Eurasia for the Director of National Intelligence. In this role, Pierson oversaw the production of the 2016 ICA, for which she received the President’s Meritorious Rank Award for Senior Intelligence Service officers in January 2017.

Pierson served as the “crisis manager” for the Director of National Intelligence during the 2018 midterm elections. In 2019, Pierson was appointed as the first Election Threats Executive (ETE) within the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, where she was responsible for overseeing US election security efforts. It was in this role that Pierson testified before the House Intelligence Committee on February 13, 2020, that Russia was working to help get Donald Trump re-elected in the upcoming November 2020 Presidential election. While Pierson did not suffer any immediate censure for her testimony (the same cannot be said of her boss, acting Director of National Intelligence Joseph Maguire, who was replaced by Richard Grenell on President Trump’s orders because of Pierson’s Congressional briefing.) Pierson eventually left her job as the Elections Threat Executive, taking up a manager-level position within the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, within the Department of Defense.

The other senior CIA official was Julia Gurganus.

Ratcliffe tried his best to shield Pierson and Gurganus from the very “politicized inquiry” that Peter Clement and Elizabeth Kimber had warned about. In the case of Pierson, Ratcliffe made the case that she “did not receive or even see the final draft until just hours before the ICA was due to be published,” further noting that senior CIA management objected to the Director of the CIA’s plan “to deliver a final draft to [Pierson] on the day it was to be published as a ‘fait accompli that would jam [her], both substantively and temporally.’”

Likewise, Ratcliffe argued that Gurganus had likewise “only received the final draft for review hours before it was published,” adding that the NIO for Russia and Eurasia had “noted that with more time, ‘they could have done more’ to bolster the judgments and ‘make the presentation more elegant,’ adding that more time would have allowed the opportunity to ‘explore alternative scenarios or disconfirming evidence in a more fulsome way.’”

Both Pierson and Gurganus were on the list of 37 names published by the Director of National Intelligence, Tulsi Gabbard, on August 20, 2025, of people who had their security clearances stripped from them for having engaged in the “politicization or weaponization of intelligence” to advance personal or partisan goals, failing to safeguard classified information, failing to “adhere to professional analytic tradecraft standards” and other “detrimental” conduct.

The main question that arises from this incident is whether the actions of Tulsi Gabbard, acting on the orders of President Trump, are justified, or simply part of a grand bit of political theater in which America gets to watch a vengeful Chief Executive take down the CIA simply because the President’s feelings were hurt. To hear Michael van Landingham tell the story, the conclusion isn’t hard to reach—Putin tried to disrupt the 2016 Presidential election by tipping the scales in favor of Donald Trump. Van Landingham believed with high confidence that Putin had done it to help Trump win. “Well, he just said it,” van Landingham noted in response to a joint press conference press with Trump on July 16, 2018, in Helsinki, Finland. “And everything that has come out subsequently proved it.”

What van Landingham was referring to is the following question-answer exchange between a reporter and President Putin:

Reporter: “Did you want President Trump to win the election, and did you direct any of your officials to help him do that?”

Putin: “Yes, I wanted him to win. Because he talked about bringing the US-Russia relationship back to normal.”

On November 6, 2016, van Landingham and the rest of the fusion cell presented their initial report on Russian election interference to a select intelligence community audience; the Director of the CIA, John Brennen, later shared this briefing with the White House. The report concluded that Russia would “continue influence operations to undermine the legitimacy of the US electoral process and degrade Secretary Clinton-whom Putin expected to win-and her presumptive Administration,” seek to publish material that would “embarrass the incoming Administration” and “cast doubt on their integrity,” noting that such efforts “would also support Putin's domestic claims that the US is a corrupt, hypocritical, and undemocratic pretender to global leadership."

The only mention of Trump made by the fusion cell in their presentation was to note that “Putin did not care who wins the election,” quoting a close associate of the Russian President, and adding that that Putin had said he was “prepared to outmaneuver whichever candidate wins.”

There was no mention of Putin trying to help Trump win the election.

Moreover, van Landingham, a top CIA analyst, ignored significant contextual data that was contained in the totality of the Helsinki press briefing, such as the following statement made by President Putin: “President Trump mentioned the issue of the so-called interference of Russia when the American elections and I had to reiterate things I said several times, including during our personal contacts that the Russian state has never interfered and is not going to interfere into internal American affairs, including the election process.”

And another Putin quote: “President Trump, when he was a candidate, he mentioned the need to restore the Russia-US relationship and it’s clear that a certain part of American society felt sympathetic about it and different people could express their sympathy in different ways. But isn’t that natural? Isn't it natural to be sympathetic towards a person who is willing to restore the relationship with our country, who wants to work with us?”

Context matters, which is something van Landingham and his fellow CIA analysts seemed to have forgotten.

Michael van Landingham has told the story of how he became emotionally connected to the Russian election interference issue. Sometime in the summer of 2016, as van Landingham relates the story, he was pulled aside by a “manager” at the CIA, who had him read a sensitive intelligence report while seated in a secure conference room in the CIA Headquarters. The report, van Landingham declared, showed that Russia was trying to disrupt the 2016 US Presidential election.

By this time, van Landingham was already a member of the fusion cell and had spent weeks assessing the story surrounding the hacking of the Democratic National Committee (DNC) email server.

This report was something different.

“I think for the first time in my professional life,” van Landingham later recalled, “I felt physically ill reading something.”

What intelligence report could have possibly prompted such an emotional response from a self-described hardened Russia analyst?

In early July 2016, a human intelligence report came into CIA channels. The source was an established human asset inside Russia whose previous reports had been assessed as being reliable. The problem was that this source’s information was all secondhand, and while the subsource used in this report was identified and had authoritative insight into the topic at hand, “the exact circumstances in which the subsource obtained the information on Putin’s plans and were not explicitly clear,” the CIA operations officer who collected the information had noted in a caveat that was published with the report. Moreover, it was not known “how the subsource obtained the information and thus whether the fragment reflected the subsource’s opinion of Putin’s inner thoughts, Putin’s actual statements made to the subsource, or some third-person’s opinions relayed to the subsource who then relayed these to the established source.”

According to this report, “Putin had made this decision [to leak DNC emails] after he had come to believe that the Democratic nominee had better odds of winning the US presidential election, and that [candidate Trump), whose victory Putin was counting on, most likely would not be able to pull off a convincing victory."

The caveat attached to this report noted that the source’s motivations were in part driven by a strong dislike for Putin and his regime, and that the source had an anti-Trump bias. The report itself was a text fragment from a larger report which had apparently been garbled during transmission. Operational constraints prevented the CIA from seeking clarification from the source about what they were trying to say in this fragmentary report.

Curiously, there was no mention of this fragmentary report in the November 6, 2016, presentation made by the fusion cell to the Director of the CIA. Nor was it mentioned on December 5, 2016, when the FBI and Office of the Director of National Intelligence briefed the House Intelligence Committee on Russian election interference. Likewise, a draft Presidential Daily Brief for December 8, 2016, which would have reported that there was no evidence of Russian interference in the 2016 Presidential election, was pulled at the last minute, pending “new guidance” from the Director of the CIA, John Brennan. This “guidance”, issued on December 9, 2016, following a meeting with President Obama and his senior advisors in the White House, directed that a special five-person team, headed by Michael van Landingham, review 15 new human intelligence reports, including two that had been withheld from publication on the orders of Brennan himself.

One of these withheld reports was the fragmentary report that had made van Landingham feel sick when he first read it back in early July 2016.

But even then, van Landingham did not reference the fragmentary report in the first draft of what became the 2016 ICA on Russian interference, which was published on December 20, 2016. This appears odd, given the emotional gravitas van Landingham had attached to the report in question. But the reality was that the fragmentary report was literally unusable as intelligence. Making matters worse, only three of the five CIA analysts tasked with writing the 2016 ICA were cleared to read the fragmentary report in its entirety, meaning that the final product was haphazardly cobbled together by analysts who did not have the benefit of the full intelligence picture.

Only after Brennan personally intervened and insisted that the fragmentary intelligence report be included in the 2016 ICA did the information it contained make its way into the final report, which was published on December 28, 2025; it was this report which, for the first time, contained the final assessment that Putin “aspired” to get Trump elected, and assigning a high degree of confidence in this assessment given the nature of the underlying intelligence.

The fact is Michael van Landingham simply isn’t a good intelligence analyst. He is a product of an anti-Russia bias instilled in him during his undergraduate studies at Princeton (’08), and his graduate studies at Harvard (’10). In December 2012, while attached to the CIA’s Open Source Center as a junior analyst, van Landingham authored a sophomoric assessment on Russia Today (RT) titled “Kremlin’s TV Seeks to Influence Politics, Fuel Discontent in US” (for some reason—perhaps ego— van Landingham opted to include the RT report in the unclassified version of the 2016 ICA published in early 2017.)

The quality of the analysis contained in the RT report is poor, as is the simplicity of argument it contains. For anyone possessing a working knowledge of how RT operates, the contrast between reality and the fantasy portrayed in van Landingham’s report is quite stark. Like his peers, van Landingham is a product of the CIA’s 22-week Career Analyst Program, taught at the CIA’s Sherman Kent School for Intelligence Analysis, located in Reston, Virginia. A key aspect of analysis taught during this training is the critical importance of context. But the reality is that, when it comes to Russia and the institutional Russophobia that has taken root throughout the CIA, the only context that truly matters, when the chips are down, is “Russia bad, America good.”

And for an establishment outsider like Donald Trump, who had the audacity to challenge the prevailing anti-Russian narrative by daring to believe that US interests could be better served by entering into friendly relations with Russia, the inherent Russophobia of the CIA lent itself to the politicization of intelligence, the single greatest sin that can be committed as an intelligence professional.

Michael van Landingham was a Russophobe.

And his work product in support of the 2016 ICA on Russian election interference reeked of politically motivated bias against Donald Trump.

Andrea Kendall-Taylor, the former deputy national intelligence officer for Russia and Eurasia who oversaw van Landingham’s work on the fusion cell, is also a Russophobe. Kendall-Taylor, who specializes in authoritarianism and threats to democracy, received her PhD from UCLA, studying under the mentorship of Barbara Geddes, a long-time specialist on autocratic politics. Kendall-Taylor is part of a triumvirate of Geddes-trained scholars, including Erica Frantz, a professor at Michigan State University, and Joseph Wright, who teaches at Penn State, who frequently collaborate on books and articles lambasting the authoritarian nature of Putin’s Russia and, increasingly, Trump’s America.

At the CIA, Kendall-Taylor found a ready home for her anti-Putin bias, with her analysis helping underpin the so-called “Russia reset” undertaken by the Obama administration. Michael McFaul, the architect of the Obama “reset” and, later, the US Ambassador to Russia, was a big fan of Kendall-Taylor’s work, helping push her, and her views, into prominence. In 2016, while serving as the deputy national intelligence officer for Russia and Eurasia, Kendall-Taylor and her long-time collaborator, Erica Frantz, co-authored an article that appeared in Foreign Affairs, the journal of the Council on Foreign Relations, entitled “How Democracies Fall Apart: Why Populism Is a Pathway to Autocracy”.

A serving CIA intelligence officer, having identified “populism” as a threat to “democracy”, publicly lambasted the fact that Donald Trump, whom Kendall-Taylor describes as a “populist”, was just elected as President of the United States.

At the time this article was published, Kendall-Tyler was overseeing the work of the CIA’s fusion cell to produce the 2016 ICA that would—wrongly—claim that Vladimir Putin “aspired” to have Donald Trump elected. In a February 2020 interview with CBS, Kendall-Taylor defended the conclusions reached by the 2016 ICA. “The report itself was based on a large body of evidence that demonstrated not only what Russia was doing, but also its intent,” Kendall-Taylor said. “And it's based on a number of different sources, collected human intelligence, technical intelligence.” The evidence, Kendall-Tyler noted, was convincing and not a close call. “If you read the intelligence report,” she told CBS, “it’s the consensus view of three intelligence agencies; CIA, NSA and the FBI.”

Except that it wasn’t, and Kendall-Taylor knew it. Like Michael van Landingham, Andrea Kendall-Taylor was prepared to reimagine history to sustain an ideologically driven bias against both Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump.

The two senior directors of the Europe and Eurasia Mission Center in 2016—Elizabeth Kimber and Peter Clement—appear, on the surface, to have performed in a manner consistent with the CIA’s ideal—unbiased, nonpartisan, and driven by fact-based reality where context matters. As an operations officer, Kimber’s input on the CIA’s analytical product was limited. Moreover, in keeping with the secretive nature of a covert operator, little is known about Kimber’s ideological background. Upon leaving the CIA in 2022, Kimber signed on with Two Six Technologies, a high-growth, technology-focused provider of products and expertise to US national security customers, as the Vice President of Intelligence Community Strategy. She has remained tight-lipped about the 2016 ICA, and all other aspects of her work as a CIA employee, ever since.

Peter Clement left the CIA in 2017 and took up a position as an Adjunct Senior Research Scholar/Adjunct Professor at the Saltzman Institute of War and Peace Studies in the School of International and Public Affairs, where he teaches courses on Contemporary Russian Security Policy and Intelligence and US Foreign Policy.

Clement’s PhD dissertation at Michigan State University focused on the so-called “Congress of Victors”, as the Seventeenth Party Congress which met in the Great Hall of the Kremlin from 26 January to 10 February 1934, became known. According to a narrative popular in the West, Stalin sought to consolidate his status as the architect of the Revolution’s victory, only to be confronted by a behind the scenes revolt from regional Communist Party secretaries, ostensibly led Sergei Kirov, the charismatic Party leader from Leningrad and a close friend and associate of Joseph Stalin. Kirov’s role in the “revolt”, according to this narrative, led to Stalin ordering his murder in December 1934.

While contemporary Russian historians, having availed themselves to archival materials unavailable to Clement at the time he wrote his dissertation, have rejected the theory that Stalin ordered Kirov’s murder, US-trained scholars and analysts, like Clement, believe that this is simply revisionist history which, if left unaddressed, will undermine Russia’s fundamental transition to democracy.

Clement recently contributed a chapter, “How Putin Turned Foreign Policy Success into Strategic Defeat”, to a larger volume entitled Failure: Russia Under Putin, published in July 2025. Clement and his fellow contributors purport that Putin’s policy choices have led to Russia’s inexorable decline on the global stage, noting that Vladimir Putin has been unable to improve critical spheres of Russian national life, limiting Russia’s development and institutional stability.

It is safe to say that Peter Clement is no fan of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

This, in and of itself, is not a mortal sin.

But the willful distortion of facts for the purpose of constructing an alternative reality designed to play well to an audience ignorant of the nuance of Russian reality is.

And this is what Peter Clement has done, playing upon the credibility he has accrued as a senior CIA “Russia hand” to lure an audience unsuspecting of the fact that the very thing that makes Clement attractive intellectually—his credentials as a CIA “expert”—is that which disqualifies him from any serious discussion for the simple fact that his institutional bias permeates into every assessment, every analysis he provides on the issue of Russia. In short, Peter Clement and his fellow CIA “Russia hands” are the personification of institutionalized Russophobia. The critique Clement provides of Putin’s Russia is so far removed from the present-day reality of Russia as to make it meaningless. The fact that Clement relies upon secondary sources of information, often processed through the biased filter of the Russian political opposition class, should trigger alarms in any true student of Russia. But Clement’s CIA past provides an adequate smoke screen that obscures this structural flaw.

So it is to this very CIA past that one must turn to for the ultimate litmus test of credibility—Clement’s take on the 2016 Presidential election and the question of Russian interference. In an article he wrote for the Fall 2022 issue of Harriman Magazine, the journal of the Harriman Institute of Russian, Eurasian and East European Studies, entitled “Analyzing Russia, Putin, and Ukraine at the CIA and Columbia”, Clement goes into some detail about the production of what he terms the “January 2017 publication of the Intelligence Community Assessment ‘Russian Interference in the U.S. Election.’”

Clement states that “Mission Center analysts helped draft this assessment,” a somewhat misleading statement given that the five analysts chosen reported to channels outside the Mission Center. Clement claims that he had a “bird’s-eye view of the production and review of the assessment,” when in fact he and his Director, Elizabeth Kimber, were brought in at literally the last second to review the draft.

Clement declares that “Accumulating evidence showed that Russia had been interfering throughout 2016.” This directly contradicts the finding of the December 8, 2016, Presidential Daily Brief (PDB) which reported that there was no evidence of Russian interference in the 2016 Presidential election. Clement stated that President Obama wanted the “full story of Russia’s interference to be told,” and that on December 5, 2016, Obama “tasked the CIA, FBI, and National Security Agency to produce a highly classified assessment,” concluding that “The paper speaks for itself.”

Clement’s version of events is chronologically and factually challenged (Obama’s tasking was issued on December 9, after the December 8 PDB was pulled from publication.) The sad thing is that Peter Clement was aware of this when he wrote the passage, facts that speak volumes about the overall susceptibility of his analytical judgements to politicized group think—which, at the end of the day, is what Russophobia is.

We see this same level of susceptibility in the work of Shelby Pierson, the National Intelligence Manager for Russia in the Office of the Director for National Intelligence at the time the 2016 ICA was published. In a telling conversation with Mike Morell, the former acting Director of the CIA, in early January 2020, a month and a half before her fateful briefing the House Select Intelligence Committee where she revealed that there was new intelligence that showed Russia preferred the incumbent, Donald Trump, in the 2020 Presidential election. President Trump was enraged by the fact that he had to learn about this new intelligence from a member of Congress—Devin Nunes—who was at the briefing, and not his acting Director of National Intelligence, Joe Maguire, who was relieved of his duties shortly afterwards.

Pierson had informed the House Intelligence Committee that the intelligence the analysis suggests the Russians would like to see Trump remain in office, there was no information that that the Russians were actively taking steps to help Trump win. Pierson’s judgments, however, were heavily influenced by the events of 2016, where she acknowledges that her role was less about managing content and more about disseminating the information contained in the 2016 ICA.

However, when Morrell asked Pierson whether “it was the assessment of the intelligence community that what the Russians were doing in part was designed to hurt Secretary Clinton and help President Trump,” Pierson answered in the affirmative. Speaking about the situation as it existed in early 2020, Pierson noted that “the intelligence community assessment remains the same,” adding that “we do not assess that any other country influenced the United States election in 2016 on the scale of what the Russians did.”

Shelby Pierson is a case study in the danger of institutional bias, where one feels obligated to embrace a narrative which they cannot personally verify the veracity of, repeating it and incorporating it into their own intellectual universe. The lie that Vladimir Putin aspired to help Donald Trump win the 2016 Presidential election is manifest in every aspect of how the CIA views Russia and its leadership. The myth of Russian election interference is a poison pill used by the CIA to blind people to the reality of Russia by playing on well-established Russophobic tropes.

Shelby Pierson was in a position where she could safely challenge such baseless assertions, but she opted not to—just like every other CIA analyst involved in the creation of the 2016 ICA on Russian election interference.

Shelby Pierson was late to the game, but she paid the ultimate career-ending price for sustaining a politically charged intelligence-based conclusion that lacks obvious merit.

Julia Gurganus, the National Intelligence Officer for Russia and Eurasia at the time the 2016 ICA was researched and written, also paid the ultimate career-ending price for her involvement—the termination of her security clearance. Unlike Pierson, however, Gurganus has avoided speaking publicly about the controversy that swirled around the 2016 Presidential election and the role she played in the production of the 2016 ICA on Russian election interference. One of the main reasons for this is that, even though she took a lengthy sabbatical from the CIA shortly after the ICA was released to the public in January 2017, Gurganus remained a CIA employee, and as such had to be circumspect in everything she said or wrote.

The only publicly available information that links Gurganus to the 2016 ICA are two heavily redacted investigations carried out by Congress—one the report issued by the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, and the other the investigation undertaken by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. In both reports Julia Gurganus, in her role as NIO for Russia and Eurasia, factors prominently in a management role, supporting the production of the 2016 ICA, but not actively participating in the underlying analysis reflected in the contents of the document.

According to Volume 4 of the Senate report, Gurganus was assiduous in her work, holding numerous meetings to coordinate “the tasking, assignment of responsibilities, outline, scope and approach for the project.” Gurganus was also adamant about making sure the 2016 ICA did not make any policy recommendations to the President. She also reached out to both the National Security Council and the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research for comments on the draft 2016 ICA document.

In short, there was nothing that jumped out from the heavily redacted reports derived from the pair of Congressional investigations that Julia Gurganus had deviated in any way from the professional and ethical standards mandated by her work as a National Intelligence Officer.

But all wasn’t as copacetic as the heavily redacted reports made things out to be. In between the vast swaths of black which obscured the words that ostensibly underpinned the case against Russia—words the American people were not allowed to see—were clues as to the ideological framework around which the drafters of the 2016 ICA constructed their arguments.

One of these clues rested in the way the 2016 ICA articulated one of its key judgements regarding Russian efforts to influence the 2016 election, namely that these efforts “represent the most recent expression of Moscow’s longstanding desire to undermine the US-led liberal democratic order.”

First and foremost, the concept of a “US-led liberal democratic order” is a singular construct of the United States, a term created by American political scientists and policy makers to describe a post-Cold War reality that emerged following the collapse of the Soviet Union. The ascribe Russian intention to respond to a concept conceived and defined by the United States is intellectually dishonest, since the American understanding of what constitutes the “US-led liberal democratic order” might differ significantly from that of the Russians.

But the reality is that even the CIA’s top Russia experts don’t agree with the foundational construct of this key judgement. In a June 2018 panel discussion hosted by the Center for the National Interest, three former senior CIA officers pointed out the reality that it was the United States itself that represented the greatest threat to the so-called “US-led liberal democratic order”, not Russia.

“I don’t think that Vladimir Putin, who I think is a realist, wants to destroy us or our democracy, (though) they did meddle…and they will do it again if they can,” Milton Bearden, who served as a Chief of Station in Moscow and managed the CIA’s covert support to the Afghan insurgency against the Soviets in the 1980’s. “They will continue to stir the pot, (but) I think they’re as amazed by what we’re doing to ourselves as perhaps we are.”

Peter Clement agreed. “I don’t think Putin seeks to destroy the US. A lot of our internal domestic problems are in fact of our own doing, (though the Russians) have very skillfully exploited it.”

“I would submit today that the United States is going through a period of rather significant domestic problems, a crisis in confidence that is generated largely from within,” George Beebe, the former head of Russia analysis at the CIA, said. “We’re projecting many of those domestic problems and fears onto Russia. In truth, we’re doing plenty of that damage to ourselves and by ourselves.”

The fact of the matter is the entire controversy surrounding the allegations of Russian meddling in the 2016 Presidential elections was a self-inflicted wound born of the deep ideological divide that existed between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump. Russia had nothing of substance to do with this home-grown crisis but was rather introduced into the mix by the Democratic Party, inclusive of a sitting President, which used the US intelligence community and law enforcement agencies to create the perception of Russian interference.

The inability of Gurganus and the drafters of the 2016 ICA to engage in the same sort of honest intellectual reflection that Beardon, Clement and Beebe did is telling, because it is reflective of a desire not to look for the truth so much as to ascribe blame to Russia, even when Russia is blameless.

This is one of the symptoms of systemic Russophobia.

Russophobia rears its head in many ways. Throughout the Senate report on Russian election interference, the investigators used the same language to justify the conclusions reached by the drafters of the 2016 ICA, noting that the use of sources “supports logically defensible conclusions that are consistent with proper analytic standards.”

Logic is defined as “a science that deals with the principles and criteria of validity of inference and demonstration” or, more simply put, reasoning conducted or assessed according to strict principles of validity. For something to be viewed logically, therefore, it must be “of, relating to, involving, or being in accordance with logic.”

It is hard to evaluate the efficacy of the sources used by the drafters of the 2016 ICA when one is denied access to, or even knowledge of, the information they are purported to contain. The investigators who wrote the Senate report, however, were very specific in their language.

And words have meaning.

The sources used to draft the 2016 ICA must not only exist in accordance with logic, and as such meet the principles and criteria of validity but also be consistent with proper analytic standards.

How the Senate investigators apply these basic precepts can be discerned in the one source that they did reference whose veracity could be independently explored.

Amid a sea of black redactions in the Senate report, on page 87, a single sentence appears: “The term ‘neighbors’ is nomenclature the Russian intelligence services have used to refer to each other going back to the 1930’s”

The footnote for this single sentence cites a 1999 book, The Haunted Wood, which describes Soviet intelligence activities in the US during the Stalin era and draws on Soviet intelligence service archives accessible in the 1990’s.

The intent of this sentence is transparent—to demonstrate a seam of connectivity to Soviet espionage that took place in America in the 1940’s to Russian election interference that was alleged to have transpired in 2016.

However, for proper analytic standards to apply, the source must be scrutinized for accuracy and context.

The Haunted Wood was co-authored by Allen Weinstein and Alexander Vassiliev. Weinstein was the son of Russian Jewish immigrants who in 1983, during the Reagan administration, co-founded the National Endowment for Democracy. The NED was supervised from its creation until 1987 by Walter Raymond, a senior CIA officer and a member of the National Security Council’s intelligence directorate. Weinstein himself, speaking about the NED in 1991, noted that “A lot of what we [the NED] do today was done covertly 25 years ago by the CIA.”

Weinstein served as president of The Center for Democracy, a nonprofit foundation he created in 1985 to promote and strengthen the democratic process, which he ran until 2003, when it was folded into another democracy project, and the National Endowment for Democracy. He was an early Western advocate for Russian leader Boris Yeltsin, who used Weinstein as an intermediary with the US government during the August 1991 coup against then-Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev. Weinstein has been described as “the dean of the new overt operatives" who aided Russian dissidents and helped establish helped establish democratic government in Russia after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Weinstein’s co-author was a former KGB officer named Alexander Vassiliev, who had retired from the KGB in 1990 because of his opposition to Soviet leadership. In 1993 Vassiliev was approached by the Association of Retired Intelligence Officers (ARIO), a group of retired KGB operatives with close links to the new Russian foreign intelligence service, or SVR. The ARIO were offering Vassiliev and a western colleague access to the Stalin-era operational files of the KGB and its predecessor agencies in exchange for a payment of a purported $100,000 (some sources report that this figure could be as high as $1 million.)

Vassiliev approached Weinstein, who took the proposal to Random House, and American publisher, who agreed to make the payments to the ARIO.

The agreement reached with the ARIO allowed Vassiliev to review archived documents and to make summaries or verbatim transcriptions from the files, including their record numbers. This material was then submitted to a panel of the SVR's leading officials for review before being released. In 1995, however, the political climate inside Russia changed, and Vassiliev and Weinstein were informed that they would no longer be given access to the KGB archives. Vassiliev fled Russia for Great Britain in 1996, leaving behind his original notes, bringing scanned copies instead. With this material he and Weinstein completed their book, The Haunted Wood.

In 2003 Vassiliev filed lawsuits in the United Kingdom against two journalists who challenged the veracity of the documents and conclusions contained in The Haunted Wood. The journalists claimed that Weinstein and Vassiliev misrepresented many of the documents they used to source the book, noting that “the co-authors’ references and their own narrative statements cannot be checked or verified by anyone else, because they derive from excerpts ‘quoted’ out of context from KGB files closed to other researchers.”

The authors also noted that these same archives had been used by the famous Russian historian, Dmitri Volkogonov, and by staff archivists of the Foreign Intelligence Service, and by three FIS officials – Yevgeni Primakov, the director; Yuri Kobaladze, head of the press bureau; and Boris Labusov—none of whom reached the same conclusions as Weinstein and Vassiliev.

Vassiliev lost both lawsuits.

Context is everything.

If The Haunted Wood was an actual intelligence source, it would have to be contextualized as being the product of ideologically motivated authors who had to pay money to gain access to their source material. The source material used in the reporting cannot be independently corroborated. Moreover, people with similar or greater access to these same archives did not interpret the data the same way as either Weinstein or Vassiliev. Lastly, the veracity of the author’s findings derived from this archival material did not withstand scrutiny in a court of law.

If the Senate investigators contend that The Haunted Wood is indicative of the kind of sources which “supports logically defensible conclusions that are consistent with proper analytic standards”, then one must assume that the same standard applies to most if not all the intelligence sources used by the drafters of the 2016 ICA.

The Haunted Wood was cited not because the Senate investigators tested the veracity of its contents, but rather because they had placed their trust in the pedigrees and ideology of the authors. This same logical flaw exists with intelligence reporting—because it originates from classified US intelligence collection programs managed by people deemed to be intellectually and ideologically sound, the information is given credence that its actual contents would not necessarily garner on its own.

In short, the intelligence community is infatuated with the intelligence information it produces.

This is not to say that both Weinstein and Vassiliev deliberately distorted information to deceive. The fact is they were both true believers in their cause. But their dedication to the project, and their pre-disposition to see things in the archival material that may not have existed, warped their presentation of this material to their audience.

This description applies equally to most, if not all, of the Russian analysts who work for the CIA today, including Julia Gurganus. Like Gurganus, the CIA’s Russian analysts are trapped in a closed-circuit intellectual environment that appears to be stuck somewhere in between the last years of the Soviet Union and the end of the Yeltsin years. Russia, according to the world view embraced by these analysts, is either a dying superpower struggling to regain relevance, or an ill-mannered subservient nation that has forgotten its place in the world order. There is literally zero comprehension of the miracle Vladimir Putin has pulled off inside Russia over the course of the past 25 years, and zero capacity to recognize the legitimacy of this miracle even if aspects of it register on the informational radar screen of these analysts. The institutionalized Russophobia that has permeated the ranks of the CIA make it virtually impossible to view Russia through anything other than the lens of a defeated, yet defiant, foe.

One of the most difficult analytical hurdles faced by CIA Russia analysts like Gurganus is the longevity and popularity of Vladimir Putin. Rather than acknowledge that Putin has built a rock-solid foundation of support across the full spectrum of modern Russian society, these analysts are constantly looking for evidence that Putin’s hold on power is fractured and illusory. Take, for instance, an article published by Gurganus in 2017 on the Carnegie website entitled “Putin’s Populism Trap.”

Gurganus argued that Putin was part of the contemporary Russian establishment elite, differentiating him from the populist President who had prevailed in previous elections. Gurganus postulated that as an elite, Putin would not be able to successfully appeal to the average Russian voter, and as such “Putin may not achieve the strong showing in the 2018 presidential election that he needs to secure his legitimacy and cement his legacy.”

The reality is that Putin won the 2018 Presidential election with more votes than any other person who had ever run for the Russian presidency up to that time, pulling in some 56,202,497 votes—76.65% of the votes, with a 67.5% turnout. It turns out Julia Gurganus did not understand Putin, the Russian electorate, or the concepts of populism as they applied to Russia.

Likewise, Gurganus and her fellow Russia analysts have trouble properly categorizing Russia’s foreign policy posture under Putin because they fail to properly recognize the root causes of Russia’s actions outside of the boundaries of the Russian Federation. In a February 2019 article, “Russia’s Global Ambitions in Perspective”, co-authored Eugene Rumer, Gurganus’ predecessor as the National Intelligence Officer for Russia and Eurasia, the following question is posed:

“Over the past several years, the international community has witnessed the return of Russia as an important global actor. Is this a fundamentally new phenomenon, or is it the result of the Kremlin’s opportunism under President Vladimir Putin and the transformation of his foreign policy?”

“Kremlin opportunism” is then defined in one of two ways: a claim to a sphere of privileged interests around its immediate periphery, with the case of Russia’s short war with Georgia in August 2008 being held up as an example, or a refusal to accept post-Cold War security order in Europe, with the case of Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea being cited. Gurganus and Rumer assess that Russia made its move on Crimea and easter Ukraine in 1914 because of perceived NATO weakness. Likewise, the 2015 military deployment to Syria is explained away as being linked to US hesitation to become decisively engaged. “These victories,” Gurganus and Rumer conclude, “have also demonstrated to the world Russia’s propensity for risk-taking and punching above its weight.”

No effort is made to paint a realistic picture of the realities faced by Russia in the aftermath of the February 2014 Maidan coup, or the threat to Russian speakers in both Crimea and the Donbas posed by the Ukrainian nationalists who were put in power by the United States. Likewise, the authors ignore outright the role played by the United States in facilitating an Islamic fundamentalist opposition movement in Syria to the rule of Bashar al-Assad, and the role played by Iran in helping convince Russia that an Islamist victory in Syria would pose an existential threat to Russia. To do so would by necessity require both Gurganus and Rumer to acknowledge the role played by US policy in destabilizing both Ukraine and Syria and, in doing so, highlight the legitimacy of the Russian actions.

"And ye shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free."

These words, taken from John 8:32, are etched on the wall of the main entrance to the CIA’s Headquarters building.

But the CIA is not interested in discerning the truth. Rather, the job of its analysts is to sustain a narrative which supports US policy objectives. As Julia Gurganus herself noted when speaking to Senate investigators about the 2016 ICA, the CIA doesn’t make policy recommendations. But truth, when spoken in the context of a policy posture predicated on lies, is a policy recommendation. To acknowledge the legitimacy of Russia’s actions would constitute a policy recommendation to halt those US actions that triggered the Russian response, such as reigning in the ambitions of Ukraine’s US-installed nationalist government or stopping the flow of weapons and money to Islamist forces operating inside Syria. But telling the truth becomes an impossibility when one realizes that the policies being implemented in both Ukraine and Syria at their core covert CIA operations.

Russophobia is the byproduct of ignorance-based fear. When applied to the American people, the cure for Russophobia is exposure to fact-based truth and the empowerment that comes through the assimilation of knowledge. Freed of the chains of ignorance, the American people will no longer fear Russia, and policies being promulgated by the government which are built on the notion that Russia is a threat that needs to be confronted will ring hollow and eventually loose support.

But in the case of the CIA, whose purpose is to generate the fear necessary to justify and sustain America’s militaristic foreign policy posture, ignorance is the desired state. The distortions of reality which underpin virtually all the CIA’s Russia analysis is done deliberately. The CIA is not looking for the truth—just the opposite: the CIA seeks to drown the truth in a sea of lies and distortions.

Seen in this light, people like Julia Gurganus are a threat to the national security of the United States, since all they do is encourage policies of containment and confrontation when it comes to Russia. Under a President like Joe Biden, the CIA would be seen as a necessary tool to preserve the US-led liberal democratic order. But under a President like Donald Trump, who seeks to redefine US-Russian relations in a more positive direction, the CIA becomes an incompatible impediment to successful policy implementation.

Julia Gurganus did not break the law or violate her duties and responsibilities as a CIA Russia analyst. Indeed, one can say shew flawlessly did her duty as she was trained and directed.

The problem is it is this very duty which poses a threat to the national security interests of the United States in a Trump presidency predicated on the need to establish normal, peaceful relations with Russia.

Julia Gurganus was selected by CIA Director John Radcliffe to brief President Trump in the leadup to his historic Alaska Summit with Russian President Vladmir Putin.

One can be certain that her briefing wasn’t designed to help foster an environment conducive toward reaching an agreement, but rather to sow the seeds of doubt in the mind of the US President about Russia’s true goals and objectives in seeking to engage with Trump at this time.

Tulsi Gabbard was right in revoking the security clearances of Julia Gurganus. She and her ilk who populate the CIA and US Intelligence Community should not be allowed to brief the President of the United States about Russia, especially if the goal and objective of the President’s policy are centered on the legitimate pursuit of peace and co-prosperity.

The next article in this series will address the CIA’s covert operators and the role they play in facilitating and sustaining Russophobia in America today.

The average American person knows very little about Russia 🇷🇺 the average American people know very little what goes on outside of America 🇺🇸

Scott, even as a child, 5 or 6 years old, I never fell for the Russophobia hoax. Now I'm 81 and have been to Russia as a Citizen Diplomat, three times. A Shaman from Siberia helped me understand my feelings.