Don't Drink the Water

The United States seeks to impose its will on the people of Greenland. Many are shocked by this flagrant disregard for issues of sovereignty. But as history shows, it is just business as usual.

Come out, come out, no use in hiding

Come now, come now, can you not see?

There’s no place here, what were you expecting?

No room for both, just room for me

So you will lay your arms down

Yes I will call this home…

I sometimes feel like a prisoner trapped in a nightmare of my own creation.

I have always considered myself an American patriot, and to be frank, I always will.

But sometimes I wonder if the America I cherish existed only in a dream.

I watch with barely suppressed anger as the Inuit people of Greenland struggle with the reality that they are but pawns in a geopolitical power struggle powered by a modern-day version of American Manifest Destiny on steroids.

Around 52,000 people identify as Greenlandic Inuit. Together they comprise around 90% of the population of Greenland, which is an autonomous region within the Kingdom of Denmark. There are three major groupings of Greenlandic Inuit: the Kalaallit, the Tunumiit, and the Inughuit.

I bring this up because I read today how many Americans have taken up the “cause” of the Greenlandic Inuit, citing the past sins of the Danes when it comes to the treatment of Greenland’s indigenous population.

But the reality is most Americans haven’t the foggiest clue about the Inuit of Greenland.

We don’t know anything about them.

And we don’t want to.

We just want their land.

And we will stoop to any level to take it, even to the point of feigning concern for their troubled history with European colonizers.

Away, away you have been banished

Your land is gone and given me

And here I will spread my wings

Yes I will call this home

I recently finished driving across the great expanse that is the United States of America, from Palm Springs, California, to Albany, New York. I was on family business, and so the schedule and pace of travel was my own. Given the reality of my age, I opted not to try and repeat the heroics of my youth, driving 15-20 hours a day was not an option. I instead broke the trip down into a series of eight-hour drives, giving me time to take in the sights along the way.

The first leg of my journey took me from Palm Springs to Flagstaff, Arizona. I had wanted to catch the sunset over the Grand Canyon, but the weather was not cooperative, and I instead opted to get up early the next morning and try instead for the sunrise.

The weather that morning was clear, and the sunrise spectacular.

As I am wont to do, I took some time to read up on the locations I would be driving through, and the places I wanted to see. The history of the creation of the Grand Canyon National Park contains a dark side unknown to most Americans. For centuries, Havasupai Indians lived in Havasu Canyon and on the surrounding plateau, which today fall within the boundaries of the Grand Canyon National Park. They lived in the canyon during the spring and summer and farmed corn, beans, peaches, melons, and cotton. In the winter, Havasupais moved to the plateau, hunting and gathering food.

As interest in the Grand Canyon region increased (initially because of the discovery of silver and the need to support the demands of silver mining companies, and later because of tourism), a series of Executive Orders were enacted by US President, beginning with Rutherford Hayes in 1880, and ending with Chester Arthor in 1882, which stripped the Havasupai Indians of their tribal lands, confining them to what was the smallest reservation in the United States, a 518 acre plot of land that isolated them from the Grand Canyon plateaus they relied upon for their traditional way of life.

When the Grand Canyon National Park was created in 1919, the Havasupai Indian Reservation found itself surrounded by park lands. In the decades that followed, the Havasupai lobbied to have their lands returned to them, and in1975, Congress passed the Grand Canyon National Park Enlargement Act, which returned over 180,000 acres to the Havasupai, forming the current Havasupai Reservation.

All is not well, however. In July 2024, uranium ore started to be mined at the Pinyon Plain Mine, located in the Kaibab National Forest, near Tusayan, close to the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. The Pinyon Mine threatens groundwater feeding into the Colorado River and Havasupai lands. However, its operations are protected by the 1872 Mining Act. The Havasupai Tribe opposes the operation of the mine, arguing that it risks “desecrating one of our most sacred sites and jeopardizing the existence of the Havasupai Tribe.”

To date, the concerns of the Havasupai have gone unheeded.

Exploring the data bases of American history, one finds reference to Sergeant Yuma Bill Rowdy, a Havasupai Indian who served as a cavalry scout in the US Army during the final campaigns to subdue the Apache in 1890. At the Battle of Cherry Creek, in March 1890, Rowdy “trailed the Apache through some of the ruggedest terrain, the Salt River Canyon of Arizona, finding them and leading the rest of the cavalry party to their location,” a feat that earned him the Congressional Medal of Honor.

What’s that you say?

You feel the right to remain?

Then stay and I will bury you

What’s that you say?

Your father’s spirit still lives in this place,

Well I will silence you

After catching the Grand Canyon sunrise, I proceeded to drive east on Interstate 40, my destination being Albuquerque, New Mexico. On the way I stopped off at the Petrified Forrest National Park, before crossing into the Navajo Reservation.

Northeastern Arizona is known for its magnificent vistas, defined by a glorious labyrinth of canyons that include Canyon de Chelly and Canyon del Muerto, formed over the course of thousands of years as water etched paths through layers of sandstone and igneous rock to produce spectacular walls looming more than 1,000 feet above the verdant canyon floor.

For more than 5,000 years, the Canyon de Chelly was home to the indigenous peoples of the region, including the Diné, or Navajo. As the United States sought to fulfill John O’Sullivan’s vision of Manifest Destiny—the belief that God mandated American westward expansion to spread democracy, capitalism, and the American way of life throughout the North American continent—the settlers so motivated began clashing with the indigenous peoples who populated the land they coveted. In northeastern Arizona, this meant that Americans were soon in conflict with the Diné people.

In 1863 the famous American frontiersman, Kit Carson, led a military expedition against the Diné, culminating in the Battle of Canyon de Chelly. The canyon was the final fortress of the Diné, where they planned on making their final stand. But rather than directly confronting the Diné warriors, Kit Carson instead undertook a campaign of scorched earth tactics, destroying the crops and slaughtering the herds of sheep the Diné relied upon for their survival.

In January 1864 the Diné, starving and without any means of sustaining themselves, were compelled to surrender. Over 8,500 were then sent on what has become known as “the Long Walk”, a trek of almost 300 miles from northeastern Arizona and northwestern New Mexico to Bosque Redondo, along the Pecos River in eastern New Mexico. Over the course of two months, in harsh winter conditions, more than 200 Diné died of cold and starvation as they made their way to their new home. Hundreds more perished after they arrived at the Bosque Redondo reservation.

In 1868, confronted by the reality that the forced relocation of the Navajo had been an abject failure, the United States government allowed the surviving Diné people to return to their native lands, including the Canyon de Chelly, which was made part of a larger Navajo Reservation.

The exploits of the Navajo in defense of the United States are legendary. During the Second World War, hundreds of Navajo enlisted in the United States Marine Corps, where they served as “Code talkers”—radiomen who communicated in the Navajo language, which the Japanese were unable to decipher.

Here’s the hitch, your horse is leaving,

Don’t miss your boat, it’s leaving now

And as you go I will spread my wings

Yes I will call this home

I have no time to justify to you

Fool you’re blind, move aside for me

All I can say to you, my new neighbor

Is you must move on or I will bury you

Leaving Albuquerque, I drove east, toward Oklahoma City, my destination for the day. My journey took me through the panhandle of Texas where, upon reaching Amarillo, I exited the highway and headed due south, toward the Palo Duro Canyon.

Palo Duro is the second largest canyon in the United States, after the Grand Canyon. Formed from millennia of erosion created by an eponymously named creek, the Palo Duro Canyon feeds into the southern extension of the High Plains of North America known as the Llano Estacado, or “Staked Plains.”

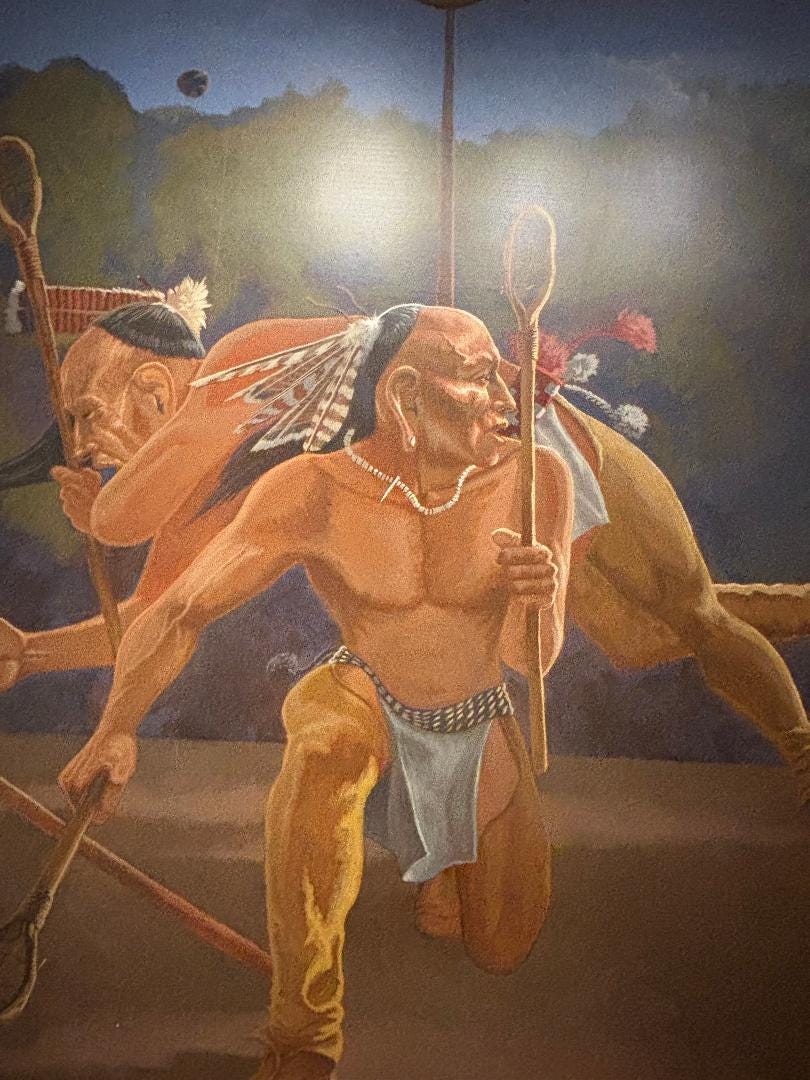

The Llano Estacado was home to the Quahadis, or Antelope, tribe of the Nermernuh people, popularly known as the Comanche, a name derived from the Ute word Komántcia, meaning literally, “anyone who wants to fight me all the time.” The Quahadis, like all of the Nermernuh people, were expert horsemen who made their livelihood hunting the hers of buffalo and antelope that roamed the Llano Estacado. They were fiercely independent, and extremely warlike. For decades they resisted the Manifest Destiny-driven encroachments of the American settlers, refusing to sign treaties with the US government and rejecting any notion of reservation life.

In 1874, the Quahadis were led by the legendary Comanche war chief, Quanah Parker. Parker made common cause with the Kiowa and Western Cheyenne Indians who had fled their reservations, and together they took refuge in Palo Duro canyon, gathering resources so that they could survive the coming winter.

In September 1874, the US Army dispatched a force of soldiers, led by Colonel Ranald Mackenzie, who cornered the Quahadis, Kiowa, and Western Cheyenne in the confines of the Palo Duro canyon. While Quanah Parker and the other tribal leaders were able to lead their peoples away from Mackenzies troops, they were forced to abandon the supplies they had been gathering, along with thousands of their best horses.

Mackenzie ordered the supplies burned and the horses slaughtered.

Starving, and without means of transportation, Quanah Parker was compelled to surrender and submit to life on a reservation.

He was the last of the free Comanche leaders.

US Army records show that 14 Comanche men enlisted during the Second World War, where they formed a special unit of Comanche code talkers assigned to the 4th Infantry Division. These Comanche landed at Utah Beach on D-Day, June 6, 1944, and fought their way across France, where they found themselves in the middle of the Battle of the Bulge. The last surviving Comanche Code Talker, Charles Chibitty, passed in June 2005. His awards included two Bronze Star medals for heroism, and a Purple Heart.

Now as I rest my feet by this fire

Those hands once warmed here

But I have retired them

I can breathe my own air

And I can sleep more soundly

Upon these pour souls

I’ll build heaven and call it home

‘Cause you’re all dead now.

My final day’s drive through territory which constituted what we American’s colloquially refer to as the “Old West” took me east, out of Oklahoma City, to Little Rock, Arkansas. As I approached the border with Arkansas, I exited Interstate 40, heading north, towards the city of Muskogee. Northeast of Muskogee one finds the town of Tahlequah where, in the original Cherokee National Capitol building, one finds the Cherokee National History Museum.

The Cherokee self-identify as the Aniyvwiya, and for centuries they lived as a united people in the southeast part of what is now the United States. On May 28, 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed into law the Indian Removal Act of 1830. The law called for “an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for their removal west of the river Mississippi.” Between 1838 and 1840, this law was used as justification for the forcible expulsion of the Aniyvwiya people from their traditional homelands to what was known as Indian Territory, which today constitutes the State of Oklahoma.

In May 1835 Andrew Jackson compelled the Cherokee leaders to sign the Treaty of New Echota, which gave the Cherokee two years to leave their ancestral homes for Oklahoma. By 1838, however, only 2,000 Cherokee had voluntarily done so. In May 1838 General Winfield Scott received a final order from President Martin Van Buren to forcefully relocate the remaining Cherokee. In the winter of 1838 this operation began, with US troops escorting some 13,000 Cherokee on a journey of more than 1,000 miles. The conditions were extremely harsh, and more than 4,000 Cherokee perished along the way in what has become known as the “Trail of Tears.”

The “Trail of Tears” is widely regarded as an act of genocide.

More than 25 million acres of land was freed up for economic exploitation by the citizens of the United States by this action.

Billy Walkabout was a Cherokee man who enlisted in the US Army and served in Vietnam. There, he was awarded the nation’s second highest medal for heroism, the Distinguished Service Cross, for action that saved the lives of several American soldiers. Billy Walkabout also earned the Bronze Star for heroism and was awarded the Purple Heart for wounds received in combat.

Billy Walkabout died in 2007 from complications arising from his exposure to Agent Orange, a defoliant extensively used by the United States in Vietnam.

And I live with my justice

And I live with my greedy need

Oh I live with no mercy

And I live with my frenzied feeding

And I live with my hatred

And I live with my jealousy

Oh I live with the notion

That I don’t need anyone but me

My travels through the United States exposed me to the reality of the sordid history of my country.

While the United States has, over the years, attempted to right the many wrongs that we committed against the indigenous peoples who occupied the land coveted by the European colonizers who later morphed into the American people, the fact is today the American Indian people are treated as second class citizens by a nation they have repeatedly defended in time of war.

Some may be shocked by the attitude taken by the Trump administration towards Greenland and the indigenous Inuit people.

But for me, it is just business as usual.

52 Danish soldiers gave their lives fighting alongside their American allies in Afghanistan. Others died doing the same in Iraq.

Don’t drink the water

Don’t drink the water

Blood in the water

Don’t drink the water

Don’t drink the water

Don’t drink the water

There’s blood in the water

Don’t drink the water

Blood in the water

You’ll all be dead

(Lyrics from the song Don’t Drink the Water, by The Dave Matthews Band.)

Excellent post, Scott. Thanks for sharing.

As I am about to complete my 76th trip around the Sun, I have come to realize that most of what we are taught by our Programmers here in the US was and is a series of endless lies to perpetuate the myth of Amerikan Exceptionalism. The lies revolve around the nation's duplicitous commitment to liberty, equality, freedom, "democracy", ad nauseum. Certainly within my lifetime, we have been at continuous war (all unconstitutional by our own law and illegal by international laws and treaties). The facts of the matter are that we are "exceptional" only in that we are particularly adept at oppressing people (especially non-white people) all around the planet and looting anyone and everyone that resides outside of the US. As Empires collapse in their death throes, their criminality is turned inward upon itself. We are there. The karmic chickens are a'roosting...

Great article Scott. My blood boiled when I read of the traitors who helped track down their native brothers.

Listen, my brother, the America you seek is called Russia. I hope you find your home there soon. Peace big man.