(Note: This is the third installment in what will be more than a dozen articles about my 26-day visit to Russia, and the lessons I learned as a result. If you enjoy this series and would like to see more content such as this, please sign up for a paid subscription or provide a donation, so that the author will be able to dedicate the time and energy necessary to continue producing quality content that embodies his motto, “Knowledge is Power,” and help overcome the ignorance of Russophobia that infects the West today.)

“To finish the moment, to find the journey’s end in every step of the road, to live the greatest number of good hours, is wisdom.” - Ralph Waldo Emerson, Experience

I often joke about being “a simple Marine.” They say that within every joke, there is an element of truth, and the fact is, upon reflection, it is in my essence to be “a simple Marine,” someone who has stripped away the complexities and contradictions of life in pursuit of a singular goal, which is service to my nation, my fellow citizens, and humanity at large.

The problem is, life isn’t that simple, and we are a product of our existence, our experiences, both individually and collectively. I was gifted with an inquiring mind, one that seeks answers beyond the fact-driven questions of who, what, and where, and instead focuses on why and how. The answers to these last two queries often assume a philosophical bent, and to prepare myself for the intellectual journey involved, I often turn to those who have been blessed with the gift of putting into words the ideas that best define life.

In college, between playing football and drinking beer, I threw myself into the pursuit of academia with the urgency of a young man who wrestled every day with the dichotomy that emerged from recognizing the need for preserving the freedoms that make life as an American so precious, and the necessity of laying down one’s own life so others might live to enjoy for themselves the American bounty.

I was a history major, and my passion for that subject drew me close to the faculty who taught me. In my senior year, they all were aware that, upon graduation, I would be taking my commission as an Officer of Marines. While they respected my patriotism, none of them were happy with my decision (most had gone through the Vietnam-era firmly on the side of the anti-war protesters), and we spent many hours discussing life in general, and the role conflict played in world history, and the consequences of such.

Scott Ritter will discuss this article and answer audience questions on Ep. 85 of Ask the Inspector.

One professor in particular, Dr. Sam Allen, sought to impress upon me the error of my ways. Dr. Allen taught Russian history and, as a Russian history major, he had mentored my intellectual development throughout my entire time in college. He was my academic advisor for my honors thesis, a two-year project the resulted in a 350-page manuscript exploring the Tsarist roots of modern Soviet military thought. We spent hours discussing the seeming contradiction of intellectual curiosity and military service, drawing upon the vast examples which could be extracted from Russian history and literature.

Seeing that he was making little progress trying to convince me of the wisdom of his position by relying on Russian sources, Dr. Allen instead turned to an American writer, Ralph Waldo Emerson. He handed me a copy of Emerson’s book, Essays and Lectures. He had placed a slip of paper between the pages of the book, with a hand-written note: “Read this. May it help guide you.”

I opened the book to where the slip of paper was placed, and found Emerson’s essay, “Experience.” As I turned the pages, I came across a passage that had been underlined, with a hand-written notation in the margin written in the labored script that was the trademark of Dr. Allen. “What value does five minutes hold for you? An hour?”

“To finish the moment,” the passage read, “to find the journey's end in every step of the road, to live the greatest number of good hours, is wisdom.”

It is not the part of men, but of fanatics, or of mathematicians, if you will, to say, that, the shortness of life considered, it is not worth caring whether for so short a duration we were sprawling in want, or sitting high. Since our office is with moments, let us husband them. Five minutes of today are worth as much to me, as five minutes in the next millennium. Let us be poised, and wise, and our own, today.

Dr. Allen and I did not discuss the issue of my joining the Marine Corps after that. A few weeks later, I walked across the stage on graduation day, wearing the dress white uniform of Marine Officer, and accepted my diploma. Dr. Allen was there to shake my hand and offer his congratulations.

I could see in his eyes that he believed I had made the wrong choice.

Landings

The pilot had announced that the aircraft was beginning its descent into Novosibirsk some fifteen minutes prior. It was close to 8.30 pm, but the sun was still above the horizon, illuminating the earth below. As I looked out the window of the Boeing 737-800, my mind was racing with several seemingly unrelated thoughts. First, I had to reflect on the fact that I was flying onboard an American-manufactured aircraft operated by an airline which, due to sanctions imposed by the US government, was prohibited from getting the aircraft serviced or from acquiring the spare parts necessary to service the aircraft itself. Media reports about Russian airline companies, such as S7, the second largest in Russia after the State-owned Aeroflot, cannibalizing their own fleets to keep a core number of aircraft operational, or about how some $9 million worth of Boeing spare parts were smuggled into Russia despite sanctions, did not put my mind at ease, especially as I watched the ailerons function, the flaps deploy, and heard the landing gear being lowered.

It was the landing gear that caught my attention—this past spring there were media reports about a pair of Russian men arrested in Arizona on charges of sanctions violations. Among the items they were accused of illegally delivering to Russia was a $70,000 brake system. I couldn’t help but wonder if that brake system had found its way onto this aircraft and, if so, whether the mechanics who installed it were competent enough to do it properly. I glanced around at my fellow passengers, most of whom were Russians returning home from business or vacation trips to Turkey. I looked at my daughter, Victoria, seated next to me, and felt a surge of anger well up inside me over the fact that some American politician had thought it a good idea to put everyone on this flight’s life at risk by denying the airliner the ability to properly maintain this particular Boeing aircraft.

As I watched the ground below the plane come into tighter focus as the aircraft reduced its altitude, I was overcome by the gravity of the moment.

I was about to land in Russia.

I had last set foot in Russia in November 1991, transiting through Moscow on my way to and from Tbilisi, Georgia, where I had married my wife, Marina, for the second time. The first wedding had taken place before a judge in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in August 1991. But that ceremony was simply a formality designed to make getting a spouse visa for Marina easier. We wouldn’t be officially married in her eyes, or the eyes of her parents and all of Georgia, until we had a proper Georgian wedding ceremony, which couldn’t be accomplished unless I flew there. There were no direct flights from the US to Georgia at the time, which meant I had to transit through Moscow.

Prior to my arrival in Moscow in November 1991, I had spent a little more than two years shuttling in and out of the Soviet Union as a member of US on-site inspection teams whose mission was the implementation of the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty. This ground-breaking agreement, signed by President Ronald Reagan and General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev in December 1987, oversaw the elimination of an entire category of nuclear weapons—the first time in arms control history that nuclear arsenals were reduced on a bilateral basis. It also represented the first time that intrusive on-site inspections were incorporated in an arms control treaty between the US and Soviet Union, a benchmark in its own right.

My destinations as an inspector were limited to Moscow and the city of Votkinsk, about 700 miles due east in the foothills of the Ural Mountains where the Soviets had built a factory that assembled several of the missiles scheduled for elimination under the treaty, including the SS-20, as well as some missiles, including the SS-25, that were unaffected by the treaty. My job as an inspector was to monitor the Votkinsk factory to make sure no missiles prohibited by the treaty (such as the SS-20) were continuing to be manufactured under the guise of being permitted SS-25’s.

When I arrived in Moscow in June 1988 the city looked and acted every bit like the capital city of the Soviet Union—massive, monumental, impressive, and intimidating, all at the same time. The same held true of Votkinsk, except on a smaller scale. By the time I left my job as an inspector, in July 1990, both Moscow and Votkinsk had been transformed—not necessarily for the better—by the policies of Perestroika that had been implemented under Gorbachev. In Moscow, a McDonalds opened in Pushkin Square on January 30, 1990. Less than two weeks later there was a massive demonstration against Soviet rule—something that would have been unimaginable two years prior.

Votkinsk had gone through a similar decline. Where once the Communist Party and the Votkinsk Factory administration held sway over every aspect of the lives of its residents, political and fiscal chaos reigned, creating shortages and a precipitous decline in the overall quality of life.

When I arrived in November 1991, some 16 months later, Moscow was a city seemingly resigned to the fact that the Soviet era was finished. The future was very uncertain. Hardline Communists had attempted a coup against Gorbachev in August 1991, and while that effort failed, Gorbachev was finished as a leader. The president of Russia, Boris Yeltsin, was coordinating with the leadership of the other Soviet Republics to determine the political future of the constituent republics that comprised the moribund Soviet state. By December 25, 1991, the game was up—Gorbachev resigned, and the Soviet Union was no more.

I had captured the events that defined the inspections and the transformation of Soviet life in a book, Disarmament in the Time of Perestroika: Arms Control and the End of the Soviet Union, that had been published by Clarity Press in September 2022. Indeed, the purpose of my journey to Russia in 2023 was to help promote this same book, which had been translated into Russian and published by Komsomolskaya Pravda under the title Disarmament Race (“Gonka Razoruzheniya” in Russian; Perestroika was a dirty word in present-day Russia, and to incorporate it into the title of a book was deemed to be bad marketing.)

As the Boeing 737-800 entered its final approach into Novosibirsk, I thought about one particular passage in my book, which dealt with my experience on a special inspection team dispatched to Novosibirsk in April 1990 to verify that a Soviet Missile Regiment—the 382nd Guards—had transitioned to SS-25 road mobile intercontinental ballistic missiles, and that no SS-20 intermediate range ballistic missiles—banned by the INF treaty—remained.

This wasn’t my first landing at Novosibirsk airport. In April 1990 I was onboard a Tu-134 transport flown by the Soviet Air Force that was transporting a team of ten US inspectors, of whom I was one, from the far eastern city of Ulan Ude to the western Siberian city of Novosibirsk. “About an hour into the flight,” I wrote in Disarmament in the Time of Perestroika, “the door to the cockpit opened, and two members of the Soviet flight crew emerged.”

I made my way over to where they stood and introduced myself, using my best broken Russian. The Soviet crewmember asked me if I was a pilot, and I tried to explain that while I was not a pilot, I was trained as a Naval Aerial Observer. The crewmember smiled, and invited me into the cockpit, where I was ushered into the navigator’s jump seat, situated behind the co-pilot.

The pilot and co-pilot were very genial and pointed out the main features of the cockpit. The aircraft was operating in autopilot mode, so both men were able to give me their full attention. After about 30 minutes or so of polite conversation, the pilot said something to the co-pilot, who got up from his seat. I assumed the tour was over, and I stood up, ready to be escorted out. Instead, the co-pilot gestured to his seat, and told me to sit down. I looked at the pilot, who nodded his head. I was now behind the controls of the Tu-134.

The plane was on direct approach to Novosibirsk, and as we got closer, we could see the airfield off in the distance in front of us. The pilot was talking to the control tower, and then looked at me, pointing to the autopilot controls, and instructed me to begin reducing altitude. This involved dialing in a new altitude, and having the plane respond on its own, leveling off once the altitude indicated was reached. Simple stuff, and I repeated this exercise several times as we approached Novosibirsk. The pilot nodded toward the airfield, nodded at my controls, and gave me a thumbs up. I returned the thumbs up, before using the autopilot to bring about another reduction in altitude. The airfield grew closer and closer, and the pilot kept looking at me as if he expected me to do something.

The realization hit us both simultaneously—he thought I was going to land the aircraft, and I had no intention of doing so because, simply put, I had no idea how to do so. The pilot shouted out “Yolki Palki,” which loosely translates into “Oh, Shit,” and grabbed the controls in front of him, effectively shutting down the autopilot. The co-pilot immediately sat down in the navigator’s jump seat, and strapped in. I remained where I was.

The pilot suddenly got busy, executing a series of violent nose-up maneuvers to help bleed off airspeed. He lowered the landing gear at a velocity far greater than it was safe to do in order to create more drag, and thus further slow the aircraft’s speed. The ground was approaching fast—too fast. The aircraft was shaking violently from the drag created by the landing gear, and the pilot’s face was as white as a ghost. I was convinced we were going to crash and prepared myself for the worst.

The plane hit the runway hard, causing the wings to flap, and then bounced back into the air, before settling down a second time, remaining on the runway and allowing the pilot to hit the reverse thrusters and apply the brakes. The end of the runway was screaming toward us…Somehow, however, the pilot was able to bring the plane to a halt, with mere feet to spare. Before taxiing in, he gestured with his head that I should exit the cockpit.

As I walked out into the main cabin, I was greeted by chaos—every overhead compartment had sprung open, and the luggage contained there scattered across the interior of the aircraft. If a seat had been occupied by a passenger, it remained upright. Otherwise, every seat had been collapsed forward due to the rapid deceleration and hard braking. Captain Williams [the inspection team leader] took one look at me exiting the cockpit and scowled. “I knew you had something to do with this,” he hissed.

My inspection was not starting off on a good foot.

As the Boeing 737-800 touched down on the runway, I was relieved that this landing had been much smoother than my previous arrival in Novosibirsk.

I was determined that this time my journey to Novosibirsk would get off to a better start.

Past is Prologue

Before departing the United States, I had taken it upon myself to do a little bit of background reading about each of the dozen cities I was scheduled to visit. It turns out that Novosibirsk, which today is the third largest city in Russia possessing the fastest growing economy, was born out of greed, not inspiration. When the Russian government began construction of what would become the Trans-Siberian Railway, in the early 1880’s, the responsible parties opted to cut costs by laying the tracks outside of major cities, thereby avoiding the need to spend money purchasing or leasing land from landowners who were asking a premium for their plots.

The original plan had the railroad going past the city of Tomsk, but the surrounding terrain, composed of swamps and wetlands, was unsuited for the construction of a bridge over the Ob River due to flooding that took place in the rainy season. Instead, the decision was made to build the bridge some 43 miles to the south of Tomsk, near the farming village of Krivoschekovo. Construction of the bridge began in 1893. Interestingly, the bridge superstructure was constructed using some 4423 tons of fabricated steel from the Votkinsk Factory, where some 94 years later I would be sent to monitor missile production as part of the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty.

Once the rail bridge over the Ob River was finished, the construction camps expanded into a town that was named Novonikolayevsk, or “New Nicholas,” in honor of Tsar Nicholas II, the ruling monarch of the Russian Empire. Novonikolayevsk rapidly grew into a major transport, commercial, and industrial hub for the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railroad as it pushed eastwards toward Vladivostok. When the rail bridge was completed in 1897, Novonikolayevsk had a population of around 7,800. Twenty years later, in 1917, the town had grown into a city of 80,000 which already functioned as the economic heart of Siberia.

This prosperity came to a crashing halt with the advent of the Russian Civil War. In December 1917 Novonikolayevsk fell under the control of the Bolsheviks, only to see the city captured by the Czechoslovak Legion and their White Russian allies in May 1918. The Legion used Novonikolayevsk as a base of operations from which they patrolled the Trans-Siberian Railway up to their eastern positions in Irkutsk. The White Army of Admiral Kolchak suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of the Bolsheviks during the summer of 1919, prompting a general retreat that extended into the winter of 1919-1920. Novonikolayevsk was re-taken by the Bolsheviks in December 1919 as the Czechoslovak Legion, weary of war, declared its neutrality, paving the way for its eventual evacuation from Vladivostok, in September 1920.

Novonikolayevsk retained its importance as the economic center of Siberia in the aftermath of the Russian Civil War, anchoring Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin’s New Economic Policy (NEP) from 1921-1923. In 1926, Soviet authorities purged Novonikolayevsk of its Tsarist heritage, renaming the city Novosibirsk (“New Siberia”). Under Joseph Stalin, who took over after Lenin’s death in 1924, Novosibirsk continued to grow as the Soviet Union’s largest commercial and industrial center, playing a major role in the implementation of Stalin’s first five-year plan, which spanned the years 1928-1932. It was this plan which marked the beginning of Soviet industrialization, and, because of it, Novosibirsk became home to some of the largest industrial factories in the Soviet Union, securing its status as one of the most important industrial centers in all of Siberia.

During the Second World War, Novosibirsk was one of the major centers of wartime production. In addition to its own industrial capabilities, Novosibirsk became the new home for more than 50 factories, and some 140,000 workers, evacuated out of the path of the advancing German armies. The Novosibirsk city planners had already begun construction for new housing and city infrastructure to deal with the pre-war industrial boom, and this infrastructure was used to absorb the relocated factories, almost all of which remained in Novosibirsk after the war.

One of the factories that made its way to Novosibirsk was Aircraft Factory Number 301. Originally operating out of the Moscow suburb of Khimki, in 1941 Factory 301 was evacuated to Novosibirsk, where it merged with the Novosibirsk Aviation Plant (NAP), named after a legendary Soviet test pilot, V. P. Chkalova, to produce thousands of the Yak-7 and Yak-9 fighter aircraft, mainstays of Soviet wartime aviation. Today NAP is home to the Sukhoi Design Bureau, and produces, among other things, the SU-34 fighter bomber, one of the most advanced aircraft of its type in the world.

In July 2020, Novosibirsk was one of 20 Russian cities awarded the title “City of Labor Valor” by Russian President Vladimir Putin. This designation was a Russian honorary title given to cities which had performed in an exemplary fashion in support of the Soviet war effort during the second World War.

Novosibirsk continued its growth in the post-war period, surpassing 1,000,000 residents in 1962. Today it serves as the business, scientific, and cultural center of the Asian part of Russia, and is the third largest city in all of Russia, behind only Moscow and Saint Petersburg. It is the capital of the Siberian Federal District, and, given its role in international commerce, is home to a regional office of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Siberian Customs Administration, and offices of other federal authorities and agencies, as well as home to the headquarters of several interregional organizations.

One of the more unique organizations in Novosibirsk is a joint-stock company known as the “Investment Development Agency of Novosibirsk,” or IDA. The IDA was created by the Governor of Novosibirsk in 2005 to help stimulate investment in Novosibirsk by streamlining and simplifying what was an otherwise stultifying bureaucracy that served to retard economic growth. The current Director of the IDA is Alexander Zyrianov, Director General. It was Alexander who invited me to visit Russia, and who helped organize every aspect of this visit, to include the publication and marketing of the Russian edition of my book, Disarmament in the Time of Perestroika.

Alexander had organized an itinerary designed to promote the book while simultaneously educating me on the realities of modern Russia, and the first day did not disappoint—a meeting with his staff at the headquarters of the IDA, followed by my first formal book event, held at the Pobeda (Victory) Theater in downtown Novosibirsk. Security concerns were prompted by the assassination of Maxim Fomin, a pro-Russian military blogger better known by his nom de guerre, Vladlen Tatarsky, in a Saint Petersburg café on April 2, 2023. Fomin’s assassination was carried out by the Ukrainian intelligence service, which operates a so-called “hit list” known as “Myrotvorets,” or “Peacekeepers.” Fomin’s name was on the list, and after his death the administrators of the list posted a photograph of Fomin with the word “liquidated” superimposed.

I am on the list as well, as are several prominent Americans whose views on the Ukraine conflict differ sharply from those of the Ukrainian government. Out of an abundance of caution, and in the interest of public safety, the decision was taken to avoid publicizing my book events until the last moment, and even then, only among persons deemed to pose no security risk. As a result, an event that could easily have drawn 1,000 or more people had a more modest attendance of around 150. My presentation was well-received, and the question-and-answer session was lively and robust. Whatever concerns I had about how my book and message would be received in Russia were alleviated by the positive atmosphere that permeated the Pobeda Theater.

Following the book event, Alexander and Ilya took Victoria and I to lunch at an upscale French-Russian restaurant, Na Dache, nestled in a lush forest about 20 minutes outside Novosibirsk. The lunch was hosted by a group of Novosibirsk businessmen, who lavished me with an assortment of traditional Russian fare while carrying out a roundtable question-and-answer session which touched upon a wide range of subjects. This discussion reinforced in my mind the absolute importance of bringing Russians and Americans together. The dialogue was free, open, and informative, both in terms of the questions asked and the answers provided. There were no softball questions, and it became clear early on that my hosts would not tolerate politically correct answers. I was left asking myself why I had to fly thousands of miles into a foreign land to have a conversation about relevant topics where all participants felt free to say what was on their minds without fear of recrimination or censorship.

Following lunch we walked over to the Green Wood Wellness Center and Spa, a hotel/resort collocated with Na Dache, where Alexander and Ilya treated me to a traditional Russian Banya (steam bath) hosted by a school-trained professional who walked us through the traditions and techniques that make the Russian Banya the experience it is (not to be left out, Victoria and Ilya’s sister, Alina, attended a “ladies only” spa at the hotel.)

When I was in Votkinsk, I often partook of the Banya. I walked away from those experiences convinced the Banya was about heat, being beaten by birch branches, ice cold water, and cognac, not necessarily in that order. The Green Wood Wellness Center host/instructor, however, opened my eyes—and my pores—to the reason behind each activity in the Banya which, as I was pleased to learn, involved a wonderful sense of smell as each phase of the experience incorporated aromatic cuttings from a variety of local trees.

We finished our first day in Novosibirsk at, of all things, a traditional American steakhouse, Goodman’s.

The next day we made our way to Akademgorodok, a self-contained city within a city located 30 miles south of Novosibirsk, to which it was officially subordinated. Founded in 1957 by the USSR Academy of Sciences, Akademgorodok was designed to be a center of scientific research and learning. In this it succeeded, growing to the size of a small city as 65,000 people—primarily scientists and their families—ended up calling it home. Besides its prowess as a center of scientific achievement and higher education, Akademgorodok gained a reputation of being an oasis of political and cultural openness, which made it one of the most sought-after places to live in all the Soviet Union.

The collapse of the Soviet Union hit Akademgorodok hard, and its population shrank precipitously as its residents, unable to continue their state-sponsored work, moved away in search of a better life. Within a few years, however, the situation in Akademgorodok stabilized as investments began to pour in, taking advantage of the brain-trust that still resided there. Today Akademgorodok serves as a business incubator, a place where innovative startups can come and perfect their business model and products before being thrown to the mercy of the market. As was the case during Soviet times, Akademgorodok enjoys a well-deserved reputation for being on the cutting edge of every aspect of Russian life, including science, technology, and education.

I was scheduled to give a second book presentation in Akademgorodok, in a conference room situated inside Academpark, what The Guardian once described as a “conjoined pair of tilting 14-storey towers” known locally as “the Geese” given its resemblance to those long-necked birds. There, The Guardian reported, teams of engineers sit, “huddled over laptops and sprawled on beanbags, working on everything from smartphone apps and portable MRI scanners to new methods of producing compost with earthworms,” a “fluorescent pyramid of innovation at the heart of Russia’s ‘Silicon Forest’” and, according to The Guardian, “President Putin’s unlikely weapon in the global tech race.”

The audience was drawn from the students, faculty, and researchers who called Akademogorodok home. As had been the case at the Pobeda Theater, they listened attentively, and then proceeded to hold me to account for my words. The quality of their queries was only matched by the professionalism of the translator, Natalie, who had been trained at Moscow State University for a career in the Foreign Ministry, but then opted instead to work in Novosibirsk—a trend I was noticing which seemed to reinforce the notion that this Siberian city was a magnet for talent able to compete for the best qualified specialists in Russia.

After the event, Alexander, Ilya, and I were treated to a lunch at the “Gusi” (“Goose,” a reference to the Academpark headquarters building where the establishment was located) restaurant and brewery, an establishment which featured American-style fare in an attractive setting where the photographs of American actors and musicians lined the walls while American songs that could have been taken from a “best of” playlist filled out the ambiance. Our table was next to a giant plexiglass window behind which once could see the giant fermentation vats used to brew the wide variety of beers featured on the menu.

“Gusi” is host to the annual Siberian Craft Beer Festival, a gathering of craft beer enthusiasts and brewers from around the world where they discuss—and consume—their art, all the while eating food prepared by the “Gusi” staff. I’ve travelled all over America, and at each destination I did my best to sample the local craft beer. As I sat and listened to the Academpark Director talk about the festival, and the diverse crowd that it attracted from around the world, I could not help but be saddened by the fact that here, in an establishment purpose-built to attract Americans, because of American sanctions, no Americans would be participating in this year’s festival. And yet the festival would take place, enriching the lives of all those who were scheduled to attend. It seemed to me that America, a nation grounded in capitalism, had gone off script.

Akademogorodok, like Novosibirsk in general, was undergoing an economic boom. Everywhere one looked, construction cranes filled the skyline as infrastructure was either being upgraded or built from scratch. In Akademgorodok, the Director was turning away applications from extremely deserving candidates. In Novosibirsk, the city planners had more funded projects than they did companies capable of bringing them to fruition. One would never know that Russia was under stringent sanctions by the US and Europe. Russia, it seemed, was open for business, and business was good.

The Value of Time

On the ride back to Novosibirsk, I reflected on my visit to Akademgorodok, what I had experienced and—most importantly—what I had learned. The short answer was that while I was accumulating several encounters with people and institutions which gave me insight into the external, physical realities of the Russian experience, I was left searching for clues about what resided inside the Russian people, and the Russian nation—the soul of Russia.

One thing I was able to come away with immediately was that my visit to Novosibirsk circa 2023 was a far different experience than the one I had back in April 1991. Back then I had a discernable purpose—treaty implementation—that provided me with a distinct mission.

As I wrote in Disarmament in the Time of Perestroika:

The late admission by the Soviets that the first stage of the SS-25 ICBM was identical to the first stage of the banned SS-20 intermediate-range missile caused more problems than just the issue of portal monitoring. While most SS-20 operating bases were scheduled to be “closed out”—meaning all INF-related systems, along with their support structures and facilities, had been removed and/or destroyed—the Soviets had indicated that some of the former SS-20 operating bases would be converted to SS-25 operating bases. During the negotiations leading up to the signing of the INF Treaty, it was agreed that the US would be able to conduct special inspections of facilities so declared, using radiation detection equipment (RDE) that would be able to differentiate between the fast neutron intensity flux produced by an SS-20 equipped with three nuclear warheads and the single nuclear warhead of the SS-25.

I had been selected to participate in the very first of the RDE inspections, and the Soviet SS-25 Missile Regiment in Novosibirsk was the first site we would inspect.

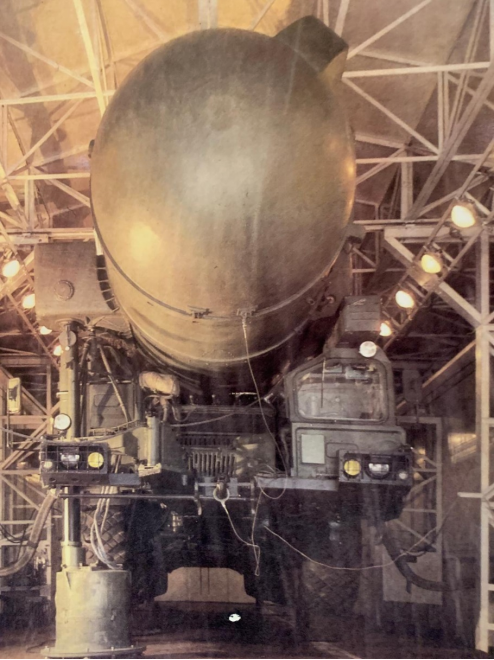

The regiment had nine SS-25 mobile launchers, each with an SS-25 launch cannister mounted. Each launcher was stored in a dedicated temperature-controlled garage, equipped with a sliding roof that could open, allowing the missile to be raised and fired from that fixed position, if necessary. The SS-25 was intended as a “second-strike” weapon, and its forte was mobile operations—it was designed to be taken out of garrison and dispersed in the forests of Siberia, making subsequent targeting by the US extremely difficult, thereby increasing its chances of survival in any pre-emptive nuclear strike.

To do the RDE inspection, each SS-25 launcher had to be pulled out of its garage and driven to a location in the garrison where the RDE equipment had been set up. The appropriate measurements would be taken, and the data double checked with the Soviet escorts. The launch cannister would then be tagged with a numbered tamper-resistant tape, placed across where the cap of the cannister joined the main body of the cannister, and then returned to its garage. My job was to escort the launchers to and from their respective garages and conduct periodic inspections to verify that the tamper resistant tags had not been tampered with or removed. This gave me plenty of time to get a close look at the SS-25 launcher and launch cannister…

Our inspection went off without a hitch, and shortly after 11 am—some 20 hours and thirty minutes into the inspection—Team Williams finished the last measurements on the last missile. Captain Williams approached me. “Now we get to look inside one of the cannisters. You have the honor of picking which one we will inspect.”

I chose missile number four, if for no other reason than the crew had been particularly good-natured. At 11.15 am I walked down to the garage where missile number four was located, verified that the tamper resistant tape was still intact, and formally designated the missile for visual inspection. The Soviets pulled the missile out of the garage and brought it to the same spot where the RDE measurements had been taken. A crane mounted on the back of a truck arrived, and the Soviets removed the cap of the launch cannister, exposing the SS-25 missile inside. A five-meter perimeter was established around the exposed cannister, inside of which the inspectors were not permitted. We had five minutes to make our observations…

When an SS-25 left the Votkinsk factory, it comprised the first, second and third stages, along with the post-boost vehicle, the equivalent of a fourth stage which allowed the missile to be maneuvered to a precise location before separating the warhead. But the warhead and associated safety and fusing systems were not attached until later, just before the missile was officially turned over to the receiving unit. The cannister lid that was in place when the missile left Votkinsk had been removed, and a launch cap, designed to be blown off prior to launch using explosive bolts, installed. One of the reasons the Soviets were reticent about allowing visual inspections of SS-25 missiles was that the missiles were sealed inside the cannister, surrounded by an inert gas to prevent corrosion. When the inspection was complete, the Soviets would have to go through a lengthy process of evacuating the normal atmosphere and replacing it with inert gas. This, albeit temporarily, took a strategic nuclear weapon out of service, something no nuclear-armed nation desires.

I was intimately familiar with what an SS-25 sans warhead looked like, based upon my observations made at Votkinsk during cannister openings. Seeing an SS-25 with its warhead attached was a new experience altogether. I did my best to note specific details but was mindful of the fact that I would be getting a second shot at examining an SS-25 at the next inspection site. I did my best to look as distracted as possible, taking no notes, and casually walking around the perimeter until our time expired.

Three and a half decades removed from that experience, I was struck by several thoughts. First and foremost was the immensity of the moment—the first ever inspection of its kind, as part of a treaty which, for the first time in the nuclear era, saw the US and the Soviet Union eliminate an entire class of nuclear weapons delivery systems.

But I was also struck by the reality that few today were cognizant of this experience, and the historic importance of the work involved. One of the purposes of writing Disarmament in the Time of Perestroika, and of having it translated into the Russian language, was to keep the memory of this time alive and, in doing so, making relevant for the present time the issue of nuclear disarmament as a mechanism to not only secure peace, but as a vehicle for improving relations between the US and Russia.

While I was pleased with the meetings that I had participated in and felt comfortable that my message was not only being heard but was resonating amongst the Russian audiences I was addressing, I continued to be bothered by my lack of insight and understanding regarding the Russian people—the Russian soul. Informing the Russians about the importance of disarmament was only part of the mission. The most important part was to capture this experience and bring it back with me to the United States so that it could be shared with a public that had largely become infected with the disease of Russophobia.

If I simply provided a chronological re-telling of my visit, my mission to defeat the scourge of Russophobia would be doomed to fail. I had to dig deeper, to try harder, to peer inside the Russian people, and in doing so, find answers to the questions about what made them who they are.

I was lost.

Alexander Zyrianov came to my rescue.

During my stay in Novosibirsk, I made it a point to get up at the crack of dawn, go to the hotel gym for a (brief) workout, and then take a walk outside to get some fresh air and take in the sights and sounds of the city as it came to life. The hotel I was staying at, the Grand Autograph (a former Marriott property that had been re-branded due to sanctions) was located across the street from Lenin Square, where statues to the Soviet Union’s founder, along with those celebrating other revolutionaries and workers from that era, were situated. Looming in the background was the Novosibirsk State Opera and Ballet.

I knew little about the history of the Novosibirsk State Opera and Ballet other than what I had read in the articles I perused before the trip. It was the largest opera and ballet building in Russia, exceeding even Moscow’s famous Bolshoi Theater in size. It had been completed during the Second World War, and its first performance was held on May 12, 1945, in honor of the victory over Nazi Germany. Other than these tidbits of information, I knew nothing more—the building was simply another structure to be admired from a distance.

I walked around the building, admiring its architecture. Giant banners proclaiming upcoming performances underscored the reality that this was a working opera and theater. But I had no feeling for how it worked, who made it work, and why it worked.

It was our last day in Novosibirsk. I had done the book event in Akademgorodok, and we had eaten lunch at the “Gusi” restaurant and brewery. I had imagined that we would return to the hotel to pack our bags, check out of the hotel, and take a leisurely ride to the airport for our follow-on journey to Irkutsk, the flight for which left that evening.

Alexander had other plans.

We were ushered into the main entrance of the Novosibirsk Opera and Ballet, where we were introduced to a dignified elderly man, who introduced himself to us. “Valery Arkadieveich Brodsky,” he said, shaking our hands. “From 1985 until 1992 I worked here as the Director. Today I serve as an assistant to the Director. It will be an honor to show you around the building.”

What followed was a journey of love. Valery knew every crack and crevice of the building, every creak of the floor, or squeaking of a door’s hinge. Listening to him, one could easily imagine barefoot ballerina’s scampering between rooms, musicians absentmindedly fingering their instruments while they waited to be seated prior to a rehearsal, or the hard-muscled stagehands sharing a laugh before returning to their tasks. Thanks to Valery, the walls of the structure sang out with the songs of hundreds of past performances, all the while echoing with the voices of its present occupants, many of whom were rehearsing as he led us through the building.

Valery had arrived in Novosibirsk in 1962 after graduating from the Tomsk Polytechnic Institute. He immediately fell in love with the building, its occupants, and the work they did. He shared this passion with his wife, Svetlana, whom he met in Tomsk. They both played in the student orchestra, and they continued their love of music and theater in Novosibirsk for the decades that followed.

As Valery guided us through this building he cherished, I began to see him not so much as a man, but as a being—something more than human, beyond simple flesh and bone, but rather a collection of experiences gathered in the shape of a man, but in their totality, so much more. Valery Brodsky was living history, someone who with a gesture of his hand, and nod of his head, a flash of his smile, and a twinkle of his eye could transform mere words into something that took hold inside you, making you a partner in the journey he had invited you to participate in.

We learned about the acoustics of each performance hall, and the unique structure of the giant dome that covered the building. We listened to the orchestra practice, not as a distant observer, but rather as one caught up in their music so much that, thanks to Valery, we made it ours. Valery, perhaps sensing that we had fallen under his spell, took to us, granting us access to areas forbidden to outsiders, such as the backstage hall where all the props and costumes for every performance ever done were stored, lovingly maintained until the next performance.

Valery Brodsky helped drive home the reality that here, in the middle of Siberia, resided one of the greatest venues of culture not only in all of Russia, but the entire world. The Novosibirsk State Opera and Ballet existed not because it was in Moscow or Saint Petersburg, well-known centers of culture, but rather because the people of Novosibirsk, in the middle of distant Siberia, demanded it. The operas and ballets that Valery Brodsky and others like him produced were performed because they were part and parcel of the people—of the people. This culture was not the purview of the elite of Russian society, but rather the birthright of the average Russian man and woman.

As the tour came to an end, and I bid farewell to Valery Brodsky, I was overcome with joy at the realization that here, at last, I had accomplished what I had set out to do—to get a glimpse of the Russian soul.

Having seen it, I wanted to know more. My journey now had purpose.

We checked out of our hotel and made our way to the airport. As the S7 Boeing 737-800 took off, heading toward my next destination, the Siberian city of Irkutsk, I settled warily into my seat. (I was still concerned about the landing gear, and whether the sanctions imposed on Russia by the US had caused me and the other passengers to board a potential death trap.)

Once the wheels were up and the aircraft safely on its way, I reflected on the last time I departed Novosibirsk, more than three decades ago, and the adventures that awaited me as I landed in Ulan Ude.

I told the story of this flight in Disarmament in the Time of Perestroika:

The weather during the two inspections had been cold but clear. Now that we were preparing to fly back to Ulan Ude, however, clouds were forming on the horizon, a sure sign that a storm was blowing in. Given the strict time requirements set by the treaty, which limited how much time we could spend at a given location, we would be landing at Ulan Ude at night. As we approached Ulan Ude, the Tu-134 was buffeted by extreme turbulence brought on by a severe thunderstorm, which shredded the sky with sheets of lightning accompanied by driving rain. The aircraft was struck on two separate occasions by lightning, which lit up the wingtips and startled everyone onboard with the accompanying instantaneous thunderclap. Making matters worse, the weather had closed in over Ulan Ude, reducing visibility to near zero and the cloud ceiling to a few hundred feet above ground level. When Captain Williams suggested to the Soviet escorts that consideration be given to landing at another airfield, he was told there was not enough fuel onboard to do anything other than land at Ulan Ude. Moreover, we would only get a few passes at the runway.

The lightning strikes appeared to have disabled the aircraft’s navigation instruments, meaning the Tu-134 had to execute a visual flight rules (VFR) landing in conditions that made this nearly impossible. The first order of business was for the aircrew to find the airfield. This was accomplished by slowly reducing altitude under we got below the cloud cover, and then rapidly scanning for any physical feature that could be used to orient the aircrew. On our first attempt, we were able to find Ulan Ude off to our right, but we were so close to the ground that the Tu-134 was compelled to climb back into the clouds before trying to reorient toward where the airfield should be. A subsequent pass put us over the airfield, but not aligned with the runway.

The navigator came back and briefed us that he needed everyone to keep their eyes peeled as the aircraft came back under the clouds, as given the lack of altitude, decisions would have to be made extremely fast. I was resigned to the fact that I was going to be a grease stain decorating the fields of the Buryat ASSR when, over the right wing, I saw the lights of the runway. I shouted to the navigator, who in turn shouted to the pilot, and the Tu-134 made an aggressive maneuver, lining up with the runway. But now the pilot had another problem—extremely high cross winds caused him to point the nose of the aircraft at an extreme 40-degree deviation from the direction of landing, meaning we were crabbing toward the runway nearly sideways. As we crossed the runway proper, the pilot tapped his rudder, swinging the nose around and touching down in a near-perfect landing.

The Soviet aircrew came out of the cockpit to bid us farewell. After my performance while landing at Novosibirsk, the aircrew had ignored me, with neither the pilot nor co-pilot even making eye contact while I was onboard. Now they were all smiles, shaking my hand and offering me their pilot’s wings.

Even Captain Williams warmed to me. “Better than the first try,” he said. “Much better.”

I hoped that my landing in Irkutsk would not be so eventful.

Little did I know at the time that the Ulan Ude landing would just be the start of an adventure that would take me half-way around the world.

In Ulan Ude Team Williams had boarded a US Air Force C-141 “Starlifter” for the trip back to Yokota Air Force Base, in Japan. As I wrote in Disarmament in the Time of Perestroika, upon boarding the aircraft “I was greeted by several of the analysts from [the US intelligence community] who had helped brief us back in Yokota.”

Once the plane was in the air, the analysts proceeded to take each inspector aside and conduct a thorough debriefing about what they had seen and experienced at each of the SS-25 sites. When my turn came, I saw that the [intelligence community] debriefers had brought a drafting kit, which could be used to make drawings of the missile and the TEL [transport erector launcher]. Between my notes and my memory, I was able to make a series of detailed drawings full of tiny technical details, including various markings that had been stenciled on the missile cannister. From what I could see, the [intelligence community] debriefers were pleased with my work…

Later, [the intelligence community] sent a letter of commendation to General Lajoie about my work at OSIA over the course of the past year. [The intelligence community] singled out my efforts during the two [short notice] inspections. According to [the intelligence community], I had been able to relate what I had learned at Votkinsk to what I observed at the two operational bases in a manner that made me the “most valuable member” of the inspection team.

Dale Carnegie, the famous American author of such books as How to Win Friends and Influence People, the core message of which was that it possible to change other people’s behavior by changing one’s behavior towards them. Carnegie’s philosophy was at the center of what I was trying to accomplish during my visit to Russia—to eliminate the Russophobia that had attached itself to the American psyche by educating them on the reality of the Russian people.

Carnegie once observed that “Knowledge isn’t power until it is applied.” I had left Novosibirsk in April 1990 having accumulated a tremendous amount of knowledge about Soviet missiles. The question now was how I would apply this knowledge.

Ten months later, having completed my tour of duty as an inspector with the On-Site Inspection Agency, I had my answer. I was attached to US Central Command headquarters, in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, where, because of my experience as an INF weapons inspector, I was assigned the task of helping with tracking down and killing Iraqi SCUD missile launchers and missiles before they could be launched against either target in Saudi Arabia. It was in pursuit of this objective that I would apply what I had learned during my time in Novosibirsk.

One of the more vexing problems we faced was the fact that, even though the Iraqi order of battle only credited them with 19 mobile SCUD launchers, by the end of the first week of the war the US Air Force had claimed more than 60 mobile SCUD launchers as having been destroyed.

And yet the Iraqis kept firing SCUD missiles into Israel and Saudi Arabia.

I launched an investigation into some of the alleged destruction sites to explore the possibility of conducting a technical investigation of any debris that might remain. The purpose of such an exercise was two-fold: to confirm whether a SCUD had been destroyed or, if not, to determine whether the Iraqis were using decoy launchers or if there was some other reason why we were simply bombing the wrong targets.

If it turned out the destroyed targets were SCUD decoys, the next step was to determine whether there were any specific technical characteristics, primarily in the form of materials used to construct any such decoy, which could assist future intelligence collection efforts in distinguishing between a real SCUD and a decoy.

A potential solution to the SCUD discernment problem lay in my previous experience as an INF inspector. Upon returning to the United States following the two inspections of Soviet SS-25 mobile ICBM bases, I travelled to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, outside of Columbus, Ohio, where I met with analysts from the Foreign Technology Division (FTD), part of Air Force Systems Command. These analysts were responsible for conducting technical intelligence exploitation and analysis of foreign military equipment. They had received copies of my drawings of the SS-25 I had made after the inspection and wanted to ask me detailed questions about what I had reported.

FTD was working on developing automatic target recognition algorithms that would be programmed into a millimeter wave radar being developed for use in the B-52 bomber as a wide-area search sensor to detect SS-25 missiles once they left their garrisons and were deployed in the forests of Siberia. For these algorithms to be able to differentiate between actual SS-25 mobile launchers and any decoys the Soviets might set up to confuse the radar, FTD needed to input as much differentiating data as possible regarding the radar cross section of an SS-25 launcher.

While the analysts at FTD had access to photographs of the SS-25 launcher, these images did not provide enough resolution to discern some of the minute details that were observable as an inspector, including insight into the materials used in construction. I spent two days working with the analysts, helping them perfect their digital model. This was a fascinating experience, providing me with insight into the nexus between intelligence and military research and development, trying to meld ground truth and laboratory-based theory into a target acquisition system that would hopefully never be used as designed.

With that experience in mind, I met with the senior Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) liaison to Central Command, Ed Valentine, and discussed the millimeter-wave radar equipped B-52’s and their potential utility in discriminating between decoy SCUDs and an actual SCUD mobile launcher. Ed was intrigued by the idea and put me in contact with analysts in DIA Headquarters (some of whom I knew well from my time as an inspector in the Soviet Union) who were now working on the SCUD targeting issue. While these analysts could not speak to whether a B-52 airframe could be made available, they did say that the radar in question could readily be adapted for use aboard other airframes, including those already deployed in the Gulf region.

The DIA already had the radar cross-section data for the SCUD missile and missile launcher—they had collected it during experiments conducted at Eglin Air Force base in November and December 1990, using an actual SCUD missile launcher. What was now needed was a detailed breakdown of the material composition of an Iraqi SCUD decoy, including dimensions, material location, and the location and positioning of radar-reflective surfaces, in particular angles. Once aggregated, this data could be used to construct a unique radar cross-section of the Iraqi SCUD decoy, which could then be loaded into the millimeter-wave radar’s computer and used to distinguish a genuine radar hit from that of a decoy.

Collecting this data from among the debris of a destroyed decoy would not be easy. Technical hand-held images would need to be collected onsite that showed the specific locations of all major metallic objects in the decoy and allow the measurement of critical angles on the missile and launcher. Likewise, material samples would need to be collected and matched to specific locations of the decoy, along with any vehicle identification numbers and data plates. Over the course of several conversations with the DIA analysts, I worked up a list of where the optimum locations on a decoy missile launcher for imagery and material collection were located.

Armed with this information, I drafted a proposal for exploiting sites where the Air Force claimed to have killed SCUDs for the purpose of reconstructing a radar cross section from the debris that could be used as a target discriminator in the millimeter-wave radar. I presented this paper to Ed Valentine, who enthusiastically endorsed the mission concept. Ed turned the proposal over to the Special Operations planners on the CENTCOM operations staff, who transformed it into a Special Reconnaissance Target Nomination.

“Mission objective is to collect technical data from [the destroyed decoy sites] to enable a determination to be made as to the validity of the reports,” the mission proposal read. “A SCUD technical advisor (Captain Ritter, USMC) is available at CENTCOM to assist in the development of assessment requirements and/or on-site analysis.”

My first effort to carry out this special reconnaissance mission was aborted. I had been working with a US Navy SEAL detachment equipped with Fast Attack Vehicles (FAVs, or heavily modified dune buggies), which would deliver me to a site I had selected in the deserts of southern Iraq where the Air Force had claimed to have killed a SCUD launcher. However, before the mission could launch, higher quality imagery showed that the site was not a SCUD, but rather a Bedouin tent.

My journey next took me to the northern Saudi Arabian city of Ar’ Ar’ where, in the city airport, special operators from the elite Joint Special Operations Command, or JSOC, had established a forward operating base from which they carried out raids into western Iraq, looking for SCUD missile launchers.

I was trying to get a Delta Force element to conduct a raid on a SCUD decoy site, where either myself or an operator trained by me would take photographs, measurements, and physical samples of the decoy, which could then be used by the Air Force to create a discernible radar cross section usable for target discrimination purposes.

Helicopter pilots from the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment—the famous “Nightstalkers”—had located several extremely realistic SCUD decoys along a stretch of highway paralleling the Iraqi border with Syria known as “SCUD Alley.” A Delta Force team was preparing to be inserted in the vicinity of these decoys, and I was trying to get them to take me to the location of these decoys so I could carry out the necessary investigations.

Shortly after I briefed the JSOC operations staff on my mission proposal, I was pulled aside by the commanding officer of the Nightstalkers unit deployed to Ar’ Ar’, Lieutenant Colonel Doug Brown. Rather than do the investigation on the ground—a risky thing to do behind enemy lines—the Nightstalker commander had a better idea. “Why don’t we just lift one of these decoys out and bring it back intact?” he asked. “One of my MH-47’s could do this with no problem.”

I liked the idea of flying a decoy SCUD out of western Iraq—a lot. I started making some initial inquiries into how best to transport an intact SCUD decoy from Ar’ Ar’ back to the United States when, without warning, my mission was cancelled. My discussion with Lieutenant Colonel Brown about flying a SCUD decoy out of western Iraq had made senior officers back in Riyadh nervous. The coalition ground attack was scheduled to begin in less than two days, and the last thing CENTCOM needed was for a serious incident to occur that would distract from the main effort. And the proposed special reconnaissance mission had all the potential of becoming a “serious incident.”

A few years later, while serving as a UN weapons inspector in Iraq, I had the opportunity to review the diaries of the Iraqi SCUD units that had been operating in western Iraq during the war. I came across an entry where the commander of the Iraqi missile forces had tasked the commander of the 22nd Special Activities Unit, responsible for deploying SCUD decoys, to “use the decoy launchers for the purpose of laying an ambush to kill or apprehend the infiltrators when they come close to the decoy launcher sites on Al Qaim-Rutba Road”—SCUD Alley. The commander of the 22nd Special Activities Unit had been directed to have the ambush in place by February 12. The diary entry confirmed that the ambush had, in fact, been prepared.

Had we gone forward with the “snatch” operation, and attempted to airlift a decoy launcher out of western Iraq using a Nightstalker helicopter, we would have run into this ambush.

A little more than 32 years later, enroute to Irkutsk, I thought about how a journey that began in the service of peace (an inspection of a Soviet missile regiment in the forests of western Siberia) ended up floundering some ten months later in the Middle East while engaged in a futile hunt for Soviet-manufactured SCUD missiles.

Every step of this journey—the inspection, the intelligence preparation, the mission planning—had led me to a moment where I found myself alone in the northern Saudi Arabian desert, with nothing to show for it but my life.

I thought back to my time in college, and the exchange I had with Dr. Sam Allen. Ralph Waldo Emerson’s words once again resonated in my head:

“To finish the moment, to find the journey’s end in every step of the road, to live the greatest number of good hours, is wisdom.”

I was wise enough to know that my first Novosibirsk journey had ended with “the greatest number of good hours” squandered.

I looked over at where Alexander and Ilya were seated and thought about all of the wonderful people they had introduced me to during my stay in Novosibirsk.

I especially thought about Valery Brodsky, Russian culture, and the Russian soul.

I glanced over at my daughter, Victoria, sitting next to me, and thought about her sister, Patricia, and my wife, Marina, who waited for us back home in New York.

“What value does five minutes hold for you?” Dr. Allen had written. “An hour?”

I had been willing to risk everything in the futile hunt for Iraqi SCUD missiles, and I had run out of time, a fact that probably saved my life.

I had now been blessed with a few more good hours to live.

The wisdom accrued from this experience informed me that I had to do better this time around.

Waging war was not the answer.

Waging peace was.

I have friends in Russia that I have known for more than 30 years! People I first met in '91 and '92, when I was living in the USSR and working at Leningrad Television. They are good people. I know them and I trust them. I will always trust them in spite of whatever hostilities arise between our nations. I am impervious to the virus of Russophobia because I am inoculated by these friends. But most people have never been to Russia and don't really know any Russians. To inoculate them, we must introduce them to Russia as we have seen it with our own eyes. I commend what you are doing, Scott. I, too, am trying to wake people up about Russia. It is a monumental task. But we will continue this important Work! Thank you for all that you are doing!

Jack,

Thanks for taking the time to comment on Chapter One of what is planned to be an 11-chappter (plus introduction, conclusion, and five vignettes) journey of discovery.

You make many assumptions about me, those I interacted with, and what the foundation of this journey is (you might want to read the introduction, published earlier, if you haven't already.)

I'm comfortable with the context from which this journey is being undertaken. So, too, are those who accompanied me on this journey.

That the journey doesn't resonate with you is a shame.

But it resonates with others, and I'll keep on writing about it.

But please do elaborate more on the context of your criticism. Are you yourself Russian? Do you reside there? Have you travelled extensively in Russia? I'm interested in whatever insights you can provide that extend beyond simple criticism of a journey you seem not willing to have the patience to let begin before you fire off your barbed arrows.

Again, thanks for your comments.

Scott Ritter