The “Shit Magnet” Patrol

Wadi al Mulusi, western Iraq, February 26, 1991

Dart Patrol.

Comprised of operators from A Squadron, 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta (better known as Delta Force), Dart Patrol represented the third foray into western Iraq by the elite American commando force in support of what had become known as “the great SCUD Hunt”, part of Operation Desert Storm, the US-led war to liberate Kuwait from its Iraqi occupiers.

One patrol of 20 men, mounted on four stripped-down Pinzgauer 6x6 offroad mobility vehicles armed with heavy weapons such as the .50 caliber machinegun and Mk. 19 40mm automatic grenade launcher.

It was, in many ways, a hard-luck patrol. Dart had inherited the mission of Axe Patrol, the first Delta Force patrol inserted into western Iraq some three weeks past, on February 7. Axe Patrol had rolled one of their Pinzgauers shortly into their mission, forcing the team to tow the damaged vehicle to a hide site where they waited for a replacement vehicle to be flown in. This took a few days, during which time Axe Patrol was out of the fight. The damaged Pinzgauer was eventually replaced and, reinforced by an additional Pinzgauer and Delta Force operators, Axe Patrol finished out its mission without further incident. On February 18, fresh personnel were flown in to replace the original Axe team. The new patrol was re-named Dart.

On the night on February 20, the Dart Patrol leader, a veteran operator named Patrick Hurley, fell down the side of a wadi while inspecting observation posts that had been set up around the patrol hide site, badly injuring his back. A helicopter flown in the next night to evacuate Hurley crashed on the way back to Saudi Arabia, killing Hurley, two Delta Force medics, and the helicopter’s four-man crew.

This opening act had earned Dart Patrol the sobriquet “shit magnet” from their comrades in arms back at their forward operating base in Ar’ Ar’, Saudi Arabia, given the bad luck that it seemed to attract.

Fate, however, was about to deal Dart Patrol a new hand.

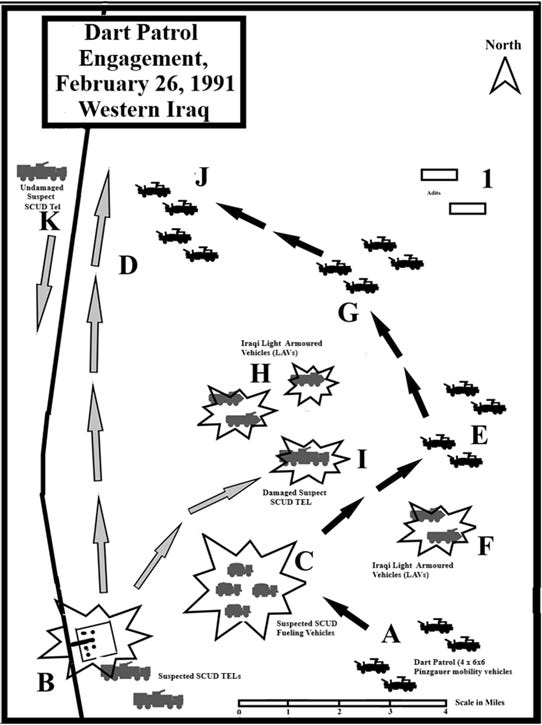

Five days after the helicopter crash, on the morning of February 26, Dart Patrol was ensconced in a hide site nestled in a vast complex of ravines and canyons collectively known as Wadi al Mulusi, which straddled the Rutba-Shab al-Hiri highway, some 20 miles north of the western Iraqi town of Rutba. From this position, Dart Patrol had tracked a pair of eight-wheeled military vehicles as they drove into a fenced compound situated just off the east side of the highway.[1]

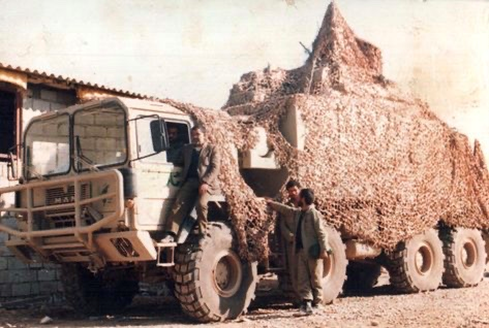

Situated in a hide site a few miles east of the compound, the members of Dart Patrol unanimously agreed that these vehicles looked like the MAZ-543 Russian-made transport-erector-launcher (TEL) use to launch the Iraqi SCUD missiles and, as such, constituted their primary targets. In the morning, an Air Force combat controller attached to the patrol contacted a US Air Force E-3 “Sentry” Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS) aircraft, callsign Cougar, flying an orbit south of the Saudi border with Iraq.

The AWACS functioned as an all-purpose airborne air traffic control center, managing the air space over western Iraq, deconflicting the dozens of aircraft that were crisscrossing its expanse. One of its missions was to receive calls for support from British and US commandos operating on the ground in western Iraq, and then vector in aircraft to bomb whatever targets the teams on the ground had identified. In the case of Dart Patrol, the troop commander (the A Squadron Sergeant Major who had assumed leadership of the patrol after Patrick Hurley had been evacuated) wanted to strike the compound in hopes of either destroying the suspected SCUD launchers in situ, or flushing them out, exposing them to follow-on attack.

Cougar put Dart Patrol’s attached air force combat controller, callsign Charlie 96, in contact with a pair of A-10 “Warthogs”, callsigns Pyro 27 and Pyro 28, from the 511th Tactical Fighter Squadron (the “Vultures”), piloted by First Lieutenant Buck Wyndham and a Captain who went by the callsign “Fang”. Charlie 96 visually guided the two A-10 pilots to the location of the compound, which Pyro 27 and Pyro 28 proceeded to attack using cluster munitions. The first A-10 in was Pyro 27, flown by Fang. As Buck Wyndham later described it, the cluster bombs dropped by Pyro 27 “plastered the place pretty well. The building was speckled with holes, and at least one of the vehicles looked like it was in bad shape.”[2]

Unable to directly observe the impact of the munitions, Dart Patrol waited to see if there was any activity in the compound. Within minutes, the two suspected SCUD launchers exited, and headed east into Wadi al Mulusi. Like a pack of wolves after a wounded animal, Dart Patrol tracked the progress of the vehicles by following the trail of leaking fluid.

One of the missile launchers, which was losing oil and in need of repair, separated itself from the second and sought refuge deeper into the wadi complex. The second launcher kept moving north, through the wadis and towards the village of Shab al Hiri. The patrol leader decided to keep tracking the damaged launcher.[3]

Dart Patrol followed the damaged launcher as it made its way through the complex of wadis and desert trails, before it came across four vehicles, which they quickly assessed as being a SCUD missile fueling point. Dart Patrol proceeded to systematically destroy the Iraqi vehicles using the machine guns and 40-mm grenade launchers mounted onboard their Pinzgauer vehicles.[4]

The sounds of combat, however, coupled with the billowing clouds of black smoke generated from numerous burning vehicles, had thoroughly compromised the patrol. Dart Patrol watched as numerous Iraqi light-armored vehicles, which they assessed to be Russian-made BTR-60s, began to converge on their location. Trapped, Dart Patrol looked for a wadi they could hide their Pinzgauer vehicles in. Meanwhile, Charlie 96 contacted Cougar, the orbiting AWACS, and announced “troops in contact”, signifying a situation of great urgency, and requested immediate air support.[5]

The “troops in contact” call got the attention of four A-10 “Warthogs” operating over western Iraq at that time. The first pair were flown by Lieutenant Colonel Greg Wilson of the 706th Tactical Fighter Squadron (the “Cajuns”) and First Lieutenant Stephen Otto, from the 353rd Tactical Fighter Squadron (the “Panthers”). Wilson and Otto had been working over targets to the east of Dart Patrol, near the Iraqi town of Al Qaim, when they started running low on fuel. The two pilots headed south, just across the border into Saudi Arabia, where they rendezvoused with a KC-10 tanker, callsign Perch 40.[6]

When Wilson and Otto reached the tanker, they found Pyro 27 and Pyro 28—Fang and Buck Wyndham—in line ahead of them, with Wyndham already having begun the process of taking on fuel. Wilson announced his callsign—Nitro—and asked if he could jump in line. Wyndham pulled back, and soon Wilson and Otto, having both refueled, headed back north.[7]

Soon after leaving Perch 40, Wilson and Otto both heard the distress call from Charlie 96, and immediately diverted west, where Dart Patrol had found itself penned in by multiple Iraqi light armored vehicles. Wilson contacted Charlie 96 and, after being vectored to the targets, proceeded to drop cluster bombs on the encroaching Iraqi vehicles, destroying some and scattering the rest.

Before Wilson and Ott left, Charlie 96 passed on the location of what the team believed could be a SCUD hide site located on a ridgeline some three miles to their east. The team believed they were looking at a pair of adits (mine shaft entrances) dug into the side of the ridge, with large metallic doors. It was their belief that these adits were large enough to hold a SCUD missile

launcher, and indeed believed that the two launchers they were tracking were likely trying to make their way to these adits for safety.[8]

Wilson and Ott flew over the ridge line in question, but instead of finding adits, they discovered rectangular pits that had been dug into the ridge, filled with ammunition, and covered with tarpaulins. Believing Dart Patrol to be safe, Wilson and Ott flew off the northeast in search of additional targets.[9]

Dart Patrol continued to track the damaged SCUD TEL, following its movements as it tucked itself away deep into a wadi network. As Dart Patrol moved to closer to where the suspect SCUD TEL was hiding, however, it encountered more Iraqi light armored vehicles. Once again, Charlie 96 broadcast a “troops in contact” call to the AWACS. The next two A-10’s that were vectored in were flown by Fang and Buck Wyndham, Pyro 27 and Pyro 28, the same pilots who had supported Charlie 96 earlier that morning.[10]

“Charlie 96 was in trouble,” Wyndham recalled. “We were instructed to contact them on the same frequency as before, and this time the team leader’s voice had a certain edge to it. They [Dart Patrol] had moved a mile or two up the wadi to the east, and now they were seeing light armored vehicles (LAVs) approaching them from multiple directions.”[11]

The two A-10’s flew over Charlie 96’s position, and then had the combat controller talk them onto their targets. What followed, Wyndham noted, “was a horror show.”

Fang engaged the Iraqis first. “The vehicle was slowly moving along the north edge of the wadi, up on the flat desert overlooking the valley. His [Fang’s] Maverick blasted it into a million pieces. We heard somebody say ‘Hooah!’ on the radio, which was really all that was necessary.”

Wyndham’s turn came next. He targeted another LAV that was driving through the center of the wadi. “The contrast was perfect,” Wyndham recalled, “and the dark color of the vehicle stood out against the light-colored sand. Another flash of fire. Another ‘Hooah!’.”

Fang rolled in for another run, taking out two LAVs with a single Maverick. “They were sitting right next to each other,” he told Wyndham over the radio.

Wyndham had one more Maverick available, and it just so happened that Dart Patrol had one more target for Wyndham—the SCUD launcher. The damaged vehicle had taken up a position further east, in a position surrounded by sharp-edged ridgelines. The launcher looked abandoned to the team, but they still wanted to finish the job. After some effort, the team was able to get Wyndham on target. “My Maverick,” Wyndham observed, “did its job perfectly.”[12]

Dart Patrol had eyes on the target when Wyndham fired his Maverick into the center of the vehicle, lifting it off the ground with the force of the explosion, and breaking it in half. Charlie 96 thanked Wyndham and Fang profusely, both for helping get them out of a tough situation, and for destroying the SCUD launcher they had been tracking for the better part of the day.

Wyndham and Fang returned to their base, while Dart Patrol proceeded to make its way out of the wadi network, heading north, eventually establishing a hide site positioned due east of the highway, where they could keep watch for the second SCUD launcher. A few hours later, Wyndham and Fang returned to check in on Dart Patrol, which reported that they were settling down for the night.[13]

After the action of the previous day, Dart Patrol spent February 27 operating from their hide site, looking for the remaining SCUD launcher. That night, however, they received word from their headquarters in Ar’ Ar’ that a ceasefire was scheduled to begin at 8 am on the morning of February 28. Dart Patrol was instructed not to initiate any action for any reason save to prevent a SCUD missile from being launched against Israel. The ceasefire took effect with Dart Patrol still in its hide site.[14]

At 9 am, the SCUD launcher emerged from wadi, and headed south, toward the H-3 airfield complex. From Dart Patrol’s perspective, the launcher was carrying a missile without its warhead, with the missile body covered by a tarp which was flapping in the wind. The war over, all Dart Patrol could do was watch the Iraqi mobile launcher drive away. The patrol members took solace in the fact that they had a confirmed kill of at least one SCUD launcher; no ceasefire could take that away from them.

An Accounting Issue

Iraqi Military Industrial Committee Headquarters, Baghdad. October 29, 1992

The Wissam al-Rafidain (“Order of the Two Rivers”) is named for the two great rivers of Iraq, the Tigris and Euphrates. It is the highest award that can bestowed on a military officer for service to the Republic of Iraq. The award comes in four classes; the first, or highest, is presented as a sash worn across the chest, with the second-class award suspended on a red moiré ribbon, with thin black stripes at each edge and in the center, being worn around the neck. The third and fourth classes are awarded as simple medals.

The award itself consists of a circular silver star, maroon-enameled, of seven points, each point ending in a ball. Between the points lies a wreath in green enamel embellished with white flowers. In the center, a white circle with an Arabic inscription (Al-Jamhuriya al-Iraq/Hub al-Watan min al-Iman, or “The Republic of Iraq/Loving the Country is Faith”) that surrounds the silver eagle of the Republic. The award is suspended from its ribbon by a wreath with crossed swords.

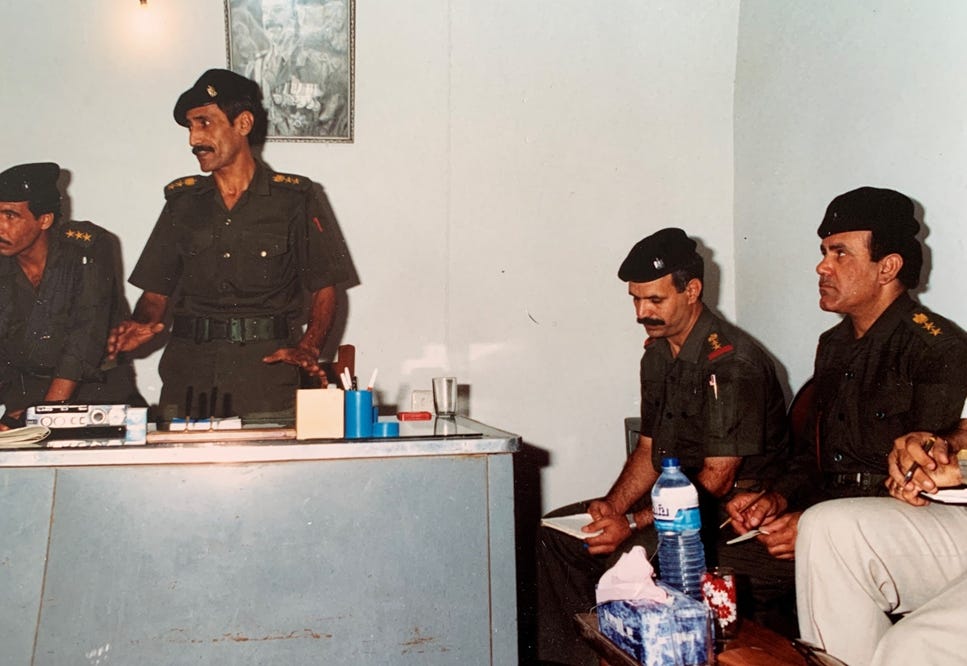

To be awarded the Wissam al-Rafidain is a rare honor, especially if it involves either of the top two classes. To be awarded it a second time is virtually unheard of. And yet the man seated at the table across from me, Hazem Abd al-Razzaq Shihab Ayoubi, on occasions requiring him to wear the formal uniform of a Major General of the Iraqi Army, would be displaying both a sash and neck devise, indicating the award of both the first- and second-class categories of the Wissam al-Rafidain.

Hazem Ayoubi was awarded the Wissam al-Rafidain, Second Class, in the aftermath of the Iran-Iraq War, while serving as the commander of Unit 224, a Brigade-sized force equipped with Iraqi-modified Russian-made SCUD-B missiles known as the Al Hussein. Between February and April 1989, the General had directed the launching of 189 Al Hussein missiles at major Iranian cities, including the capital, Tehran. Over the course of 52 days these attacks broke the spirit of the Iranian people, thereby compelling the Iranian government to sue for peace, bringing that conflict to an end after eight years of bloody fighting.

The award of the Wissam al-Rafidain, First Class, came at the end of the 1991 Gulf War, during which time Hazem Ayoubi led a campaign which saw his forces fire 93 more Al Hussein missiles against coalition targets on the Arabian Peninsula and in Israel without losing a single mobile launcher or missile to enemy action. Iraq may have lost the 1991 Gulf War (better known in the West as Operation Desert Storm, and in Iraq as the Umm al-Ma’arik, or the “Mother of all Battles”.) But when it came to the missile campaign conducted by Hazem Ayoubi and the men of the Al Hussein Force during that conflict, their struggle was viewed by the Iraqi people as a victory unlike any in the annals of modern warfare.

The twice-decorated hero of Iraq, flanked by his fellow officers from the Al Hussein Missile Force that he had led in combat a little less than two years ago, was now confronted by international inspectors who had been mandated by the United Nations Security Council to question him in detail about matters which, up until this moment, were considered sensitive national security secrets by the Iraqi government. As the person who conceived the inspection that was charged with investigating Hazem Ayoubi’s wartime actions, I took the leading role in facing off against this Iraqi living legend.

How Hazem Ayoubi’s ended facing off against an upstart former Marine intelligence officer was a direct result of Iraq’s defeat in the 1991 Gulf War. When Iraq invade Kuwait, on August 2, 1990, the international community, through the United Nations Security Council, responded by imposing sweeping economic sanctions which were to remain in place until which time Iraq withdrew. Efforts by the international community to compel Iraq’s withdrawal from Kuwait ended in failure. Instead, the United States took the lead in mobilizing an international coalition empowered by the Security Council to use military force to evict Iraq from the territory of Kuwait. The result was the Gulf War, popularly known by its American name, Operation Desert Storm. The military assault on Iraq began on January 17, 1991. By February 28 it was over, the Iraqi military defeated and in full retreat, and the territory of Kuwait once again under sovereign control.

With Kuwait liberated, the legal justification for the continuation of economic sanctions no longer existed. The Security Council, however, extended the sanctions, this time predicating their termination on Iraqi being fully disarmed of its weapons of mass destruction (WMD)—chemical and biological weapons, nuclear enrichment infrastructure, and ballistic missiles with a range greater than 150 kilometers. To this end, the Security Council authorized the creation of an inspection organization, the United Nations Special Commission, or UNSCOM, which was given the responsibility to verify Iraqi compliance with its disarmament obligation.

UNSCOM inspection teams had been on the ground in Iraq since May 1991. I joined the organization in September 1991 as UNSCOM’s resident intelligence and missile expert. By October 1992, I had participated in four major inspections, all of which were focused on accounting for Iraq’s ballistic missiles.

Iraq was obligated by the terms set forth in the Security Council resolution creating UNSCOM to provide the inspectors with a full, final, and complete disclosure of the totality of their WMD holdings. The initial Iraqi declaration, delivered to the UN in April 1991, was a lie, with Iraq trying, among other things, to maintain a covert missile force of five Russian-made MAZ-543 transport erector-launchers (TELs) and some 86 Al Hussein missiles.

The pressure from the inspectors was too great, however, and Iraq, concerned it would be caught in this lie and exposed to even more stringent economic sanctions (or worse, a renewal of the war) opted to destroy this covert force in secret. To hide the existence of this force from the inspectors, the Iraqis concocted a cover story that accounted for each launcher and missile. This cover story, however, did not withstand the scrutiny of the inspectors, and by March 1992 the Iraqis were compelled to come clean, admitting both the existence of the covert missile force and its fate, and issuing a new declaration it purported to be a genuine “full, final, and complete” accounting of its missile and launcher inventory.

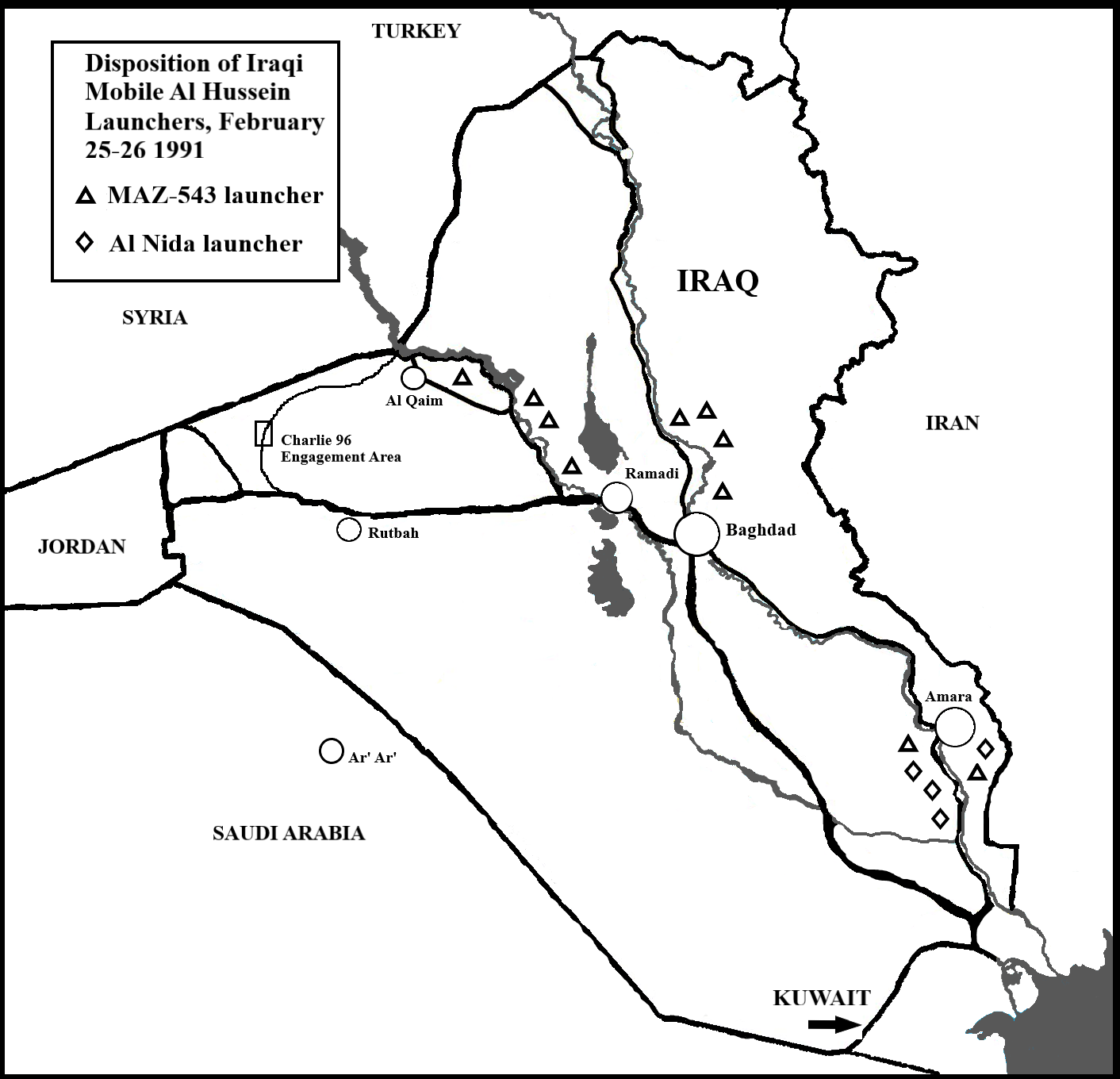

Iraq had declared a wartime inventory of 20 mobile missile launchers. Eleven of these were Russian-made MAZ-543 TELs (ten of which were operational.) The remaining nine were indigenously produced Iraqi mobile launchers, one a variant known as the Al Nida (Iraq produced a total of six, four of which were operational), and the remaining three known as the Al Waleed (none of which were operational.) In short, during the Gulf War Iraq had 14 operational mobile launchers capable of firing the Al Hussein missile.

However, when factoring in the reality that Iraq, during the Gulf War, was launching Al Hussein missiles on two fronts—one in western Iraq, toward Israel, the other in the south, toward Saudi Arabia and the Gulf Arab States—it appeared to many observers (including myself) that it was impossible for Iraq to sustain the rate of missile launches on record with only 14 operational launchers. The UNSCOM inspectors, together with several supporting nations led by the United States and the United Kingdom, suspected that Iraq was holding on to an additional force of undeclared launchers.

Likewise, the Iraqi accounting for missiles was suspect, especially when one considered the claims by Iraq that not a single missile had been destroyed. While it would make more sense for Iraq, if it were maintaining a covert missile force, to claim that missiles had been destroyed by coalition forces during the war, the fact is the UNSCOM ledger could not be balanced so long as this discrepancy existed.

To resolve this issue, the Executive Chairman of UNSCOM, a Swedish diplomat named Rolf Ekeus, dispatched an inspection team, known as UNSCOM 45 (the 45th inspection mission undertaken since the start of UNSCOM’s work in Iraq, in May 1991) which would, among other tasks, thoroughly investigate this issue of wartime SCUD engagements with an eye on determining if any had resulted in verifiable evidence of destruction of a launcher, a missile, or both.

In the weeks leading up to the inspection, I spent countless hours poring over reports from the US and UK about claimed SCUD kills and reviewing VHS tapes showing suspected SCUDs being destroyed by coalition aircraft. During the Gulf War, I had served on the intelligence staff of Central Command, where I was assigned duties as the battle damage assessment officer for Iraq’s SCUD missile force. I was used to this kind of mind-numbing forensic investigation which, as had been the case during the war, invariably disproved all claims regarding a SCUD kill.

I had requested that the US and UK provide UNSCOM with a detailed list of engagements by their respective special operations forces that had resulted in claims of a SCUD launcher and/or missile being killed. While the UK eventually provided several papers detailing their claimed engagements and sightings of SCUD missiles and launchers, the US remained silent. I was told that information would be forthcoming once the inspection team assembled in Bahrain, where we conducted pre-inspection training in an aircraft hangar located within the confines of the Muharaq Air Force base, adjacent to Bahrain International Airport.

UNSCOM had assembled an impressive array of missile experts for this mission. I was the Operations Officer for the team, responsible for overseeing the execution of the various tasks we had been assigned as well as the questioning of the Iraqis. Joining me was a German technical intelligence officer, Dr. Norbert Reinecke, whose office maintained an operational MAZ-543 TEL and SCUD-B missile, along with supporting documentation and training material, that had formerly belonged to the East German Army, and which had been made available to UNSCOM to help prepare for this and other inspections.

Larry Chambers, the Defense Intelligence Agency’s premier Iraqi ballistic missile analyst whose work had factored into decisions made during the Gulf War, was also a team member. So, too, was Alexander Zgadov, a Russian Army Colonel who had commanded SCUD-B units as part of the Soviet Group of Forces, Germany, and with the 40th Army in Afghanistan. With Zgadov was a team of Russian military technicians, several of whom had served in Iraq as military advisors during the Iran-Iraq War.

These experts sat with me and the Chief Inspector of UNSCOM 45, a seasoned Russian diplomat and arms control specialist named Nikita Smidovich, as we faced off with Hazem Ayoubi and his officers inside the Military Industry Committee headquarters in a determined effort to get to the bottom of Iraq’s claims that no missiles or missile launchers had been destroyed during the Gulf War. Nikita’s maturity as a seasoned diplomat experienced in the art of arms control negotiations made him the perfect Chief Inspector, balancing my less-polished, aggressive, and direct military-style approach toward problem solving.

Nearly a week prior, on October 23, we had conducted our initial meeting with Hazem Ayoubi and his officers, which lasted for nearly five and a half hours. At that time, we discussed details about the wartime functioning of the Al Hussein Missile Force for the purpose of establishing a joint foundation of fact that would inform a series of on-site inspections of locations of interest in Iraq, including several sites associated with so-called “engagement” events.

Now, six days later, we were back, our inspection experiences having generated as many questions as they had answers to the issues that existed concerning the accounting of Iraq’s ballistic missile capability. Hazem was joined by Colonel Adnan Anjad al-Dulaimi, the commander of Unit 224, a MAZ-543-equipped brigade, and Colonel Ahmad Jasim Hamad Kuwaisi, the commander of Unit 223, comprised of indigenously produced Al Nida mobile launchers. Three regimental commanders—all Lieutenant Colonels—from Unit 224, along with Staff Colonel Ismail, who had served as the liaison between the Al Hussein Missile Force and the Iraqi General Staff during the war, were also in attendance. All wore the green uniform of the Iraqi Army.

I led off the discussion by noting that there were still outstanding questions about Iraq’s accounting of its MAZ-543 launchers. We had visited sites where the wreckage of five MAZ-543 TELs declared by Iraq to have been unilaterally destroyed in the summer of 1991 were located. We examined the wreckage from a forensic point of view and came back with a conclusion that at least two of the launchers appeared to have been destroyed by air delivered munitions.

At this point, Nikita interjected, declaring that the entire credibility of the Iraqi story hinged on the accuracy of its claims that not a single launcher had been destroyed. I leaned into the table, staring Hazem Ayoubi in the eyes. “I have very good reason to believe that the coalition destroyed at least one MAZ launcher during the war,” I said. “You’re going to have to provide more detailed information about the movement of your forces and their operations before we are going to be able to believe your story.”

My eyes were on Hazem Ayoubi, but my attention was focused on the two men who were seated with the other inspectors, off to the side of the room, away from the table where the General and I faced off. These two “experts” had the least practical knowledge of missiles among the 40-odd inspectors that comprised the UNSCOM 45 inspection. What they did possess, however, was unmatched information on wartime SCUD engagements. Paul Pisarek was an Army Major assigned to the headquarters of 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta, popularly known as Delta Force. With him was Master Sergeant Randall Rogers, a special operator from Delta Force’s A Squadron who had participated in combat operations during the Gulf War to destroy and disrupt Iraqi SCUD missile launchers and missiles.[15]

During the team training in Bahrain prior to the inspection, I had been informed that Paul and Randall had detailed information about several wartime SCUD engagements involving Delta Force, and that when the time was right, this information would be shared with me so that UNSCOM could act on it. As the training progressed, however, nothing happened. Paul and Randall were present, sitting in the back of the room, taking in everything I said about the mission. But they were silent when it came to the issue of SCUD engagements.

Finally, with two days to go in our training, Paul approached me while I was seated at a table, looking over various inspection-related material. “Look, I know you know who we are”, he said, referring to himself and a cadre of personnel, including Randall, from JSOC who were attached to the inspection team. “We know you spent time with us up in Ar’ Ar’ during the war, so there is no sense in playing games.”[16]

He sat down next to me. “But we don’t want everyone knowing about us, or what we did. I’ve been given permission to talk with you about specific operations where we feel confident SCUD launchers were destroyed. You can use this information as you best see fit.”

Paul had with him a Tactical Pilotage Chart (TPC) for western Iraq (a 1:500,000 scale military map) and a pen and started to sketch out the basic concept of operations for the deployment of what was known as the Joint Special Operations Task Force (JSOTF), which included elements from Delta Force, in western Iraq, along with a half-dozen engagement “events”.

When he finished, Paul produced another map, consisting of four 1:50,000 scale tactical charts joined into a single sheet which was annotated with grid refences matched to specific locations denoting activity of interest. “All of these,” he said, pointing to the various ‘events’ that were depicted on the TPC, “should be investigated. We don’t think you’ll find anything, but it’s worth a try. However,” Paul added, laying out the 1:50,000 map sheet, “after scrubbing all our data, we have one engagement which we have an extremely high degree of confidence resulted in a confirmed kill.”

“How can you be so certain about this one?” I asked.

Paul gave me a long, hard stare. “Because Randall, the guy with me, personally witnessed it.”

Paul then began to tell me the story of Dart Patrol, and their confirmed SCUD kill of February 26, 1991.

An Inconvenient Truth

Paul’s information, imbued as it was with such rich detail and the imperative that comes from first-hand experience, emboldened me to aggressively pursue UNSCOM’s contention that Iraq had, in fact, suffered casualties among its missiles and launchers during the Gulf War. This wasn’t the first time that I had compelled the Iraqis to admit they were lying. Indeed, just a few days back, using calculations I had come up with regarding fuel consumption rates for the Al Hussein missile, when compared to the fuel available to Iraq which had been delivered by the Soviet Union, I forced the Iraqis to admit that their previous denials about having an indigenous fuel production capability was a lie. The Iraqis were forced to declare a hitherto fore secret program, known as Project 144/7, and present the men who ran it to us for a day-long interrogation.

Hazem Ayoubi, however, was a different breed. He was a man of honor, as most military men are, and was loath to have his integrity questioned, especially in front of his men. At one point in the discussion, I accused him of presenting a ridiculously over-simplified story, one which more resembled a Boy Scout outing than a military campaign.

The commander of the Al Hussein Missile Force, twice decorated with the Wissam al-Rafidain, stared at me without speaking, as if to take the measure of the individual who had just accused him of quibbling about the facts associated with the activities and operations of the unit he commanded. The five Iraqi officers seated behind him stared at me as well. I had, in their presence, belittled the man who, as the commander of the Al Hussein missile force, had helped bring Iran to its knees in 1989, and, in his own words, “made Israel cry” during the Gulf War.

Hazem Ayoubi quickly gathered himself. “I believe even the United States military counts ‘simplicity’ among the principles of war,” he said. “Complexity becomes very difficult in a combat environment, so my plan was very simple, and it was executed as I have described. Perhaps you are doubtful because the coalition probably took many measures—unsuccessfully—to try to stop us.” He went on to provide several examples to reinforce his position. “As to being Boy Scouts,” Hazem continued, “yes, we were all Boy Scouts when we were little. And we were happy that fate allowed us to launch against Israel.”[17]

I was 31 years old. The highest rank I had achieved to that time was Captain. I was now going toe to toe with a Major General who was not only a true hero of Iraq, but who’s wartime performance would be the envy of any military professional. I could feel the presence of Paul and Randall behind me. Their account of the SCUD launcher destruction helped steel my resolve to press on aggressively, if not a little more respectfully.

For the next three hours, Hazem Ayoubi and I put on a show for his officers and the inspectors. I laid out the annotated TPC on the table (what the inspectors and Iraqis alike came to refer to as “THE map”), and the General and I proceeded to re-hash the war, day by day, launch by launch. Hazem would make a claim of a missile movement in a specific area; I would respond by noting that a critical bridge crossing a river on that route had been destroyed two days prior. The General would confer with his officers, and then counter by declaring that only one lane of the bridge had been destroyed, and that his engineers were able to make sufficient repairs for his launchers to inch their way across. I would turn to Larry Chambers, the DIA analyst, who referred to a paper listing the status of every bridge in Iraq, before acknowledging that what Hazem said was true.

This kind of point-counterpoint intellectual chess game went on for hours, and for a while I thought I was getting the upper hand. A few days prior, I had personally inspected the location where Iraq claimed to have unilaterally destroyed three of their MAZ-543 TELs that they had retained in secret. We asked about the method of destruction and were informed that the Iraqis used boxes of TNT placed around the chassis of the vehicle. I had one of my explosive ordnance disposal experts conduct a rudimentary forensic evaluation of the destroyed launchers. He reported back that on at least one the damage appeared more likely to have been caused by air-delivered munitions than through set-piece demolition. I then had my inspectors take samples from the destroyed launchers that would be tested for the presence of high explosive residue; if the TEL had been destroyed by a US bomb or missile containing RDX or HMX, the results should be different than if it was destroyed by TNT.

I started focusing in on the movement of Iraqi TELs in the last days of the conflict. The last launch against Israel was on February 25. The Iraqis had told the inspectors that they had established a location tucked away in a date grove west of the city of Ramadi, some 102 kilometers (63 miles) west of Baghdad, where the Al Hussein missiles would be fueled, their targets programed into their guidance and control units, and their warheads attached, before being transferred to a launcher with orders to fire a missile from a given place at a given time.

My contention was that because the coalition had put what the Iraqis called “infiltrator” teams on the ground in western Iraq where they could observe all movement on the major east-west highways and roads, the ability of the Iraqi missile force to operate the way Hazem Ayoubi claimed was impossible, especially when it came to moving missile-laden TELs from Ramadi into the desert of western Iraq.

Earlier in the conversation, I had coerced what I believed to be an important concession from Hazem Ayoubi about the pressure being brought to bear on his operations in western Iraq due to coalition air strikes and “infiltrator” activity. Hazem admitted that this pressure had impacted his ability to maneuver his forces. In February, he said, “we slowly began withdrawing to the rear. I encouraged my commanders to go forward when possible. I recall that one firing [missile launch] was delayed due to problems, and I ordered the commander to either H-3 or Rutba, as I felt the coalition pilots would be searching for him.”[18]

Up until that point, the Iraqi General had been adamant that his forces had operated from a network of support facilities centered around Baghdad, moving west or south as required to launch missiles at their respective targets, but always collapsing on the center when finished. With this model, the likelihood of an Iraqi mobile launcher moving west of the known launch locations in western Iraq was nil.

Since H-3 airfield (where the suspect MAZ-543 launchers were said by Paul to have originated on the night of February 25/26) was well west of every launch location used during the war, the Iraqi logic precluded any being in H-3—until now. Hazem Ayoubi had just testified that he had ordered a MAZ-543 launcher to hide in H-3 or Rutba, both well west of the launch areas. Paul’s narrative was now validated. I just had to wear down the Iraqis until they admitted—as they had done in the past—that they had not told the truth.

After another hour or so of back and forth, I felt it was time to force the issue. The Iraqis had been reticent about providing information about the locations of their launchers at a specific date and time, calling it a “military secret.” I offered a compromise--UNSCOM needed the information only for the period of February 25-26 to help dispel our concerns about destroyed launchers.

To my surprise, Hazem Ayoubi not only gave us the information we requested, but promised us access to the unit diaries to corroborate this information. According to him, one regiment of four MAZ-543 launchers was located between Al Qaim and Ramadi, moving towards Baghdad. One Regiment of four MAZ-543 launchers was in hide sites north of Baghdad. And a mixed Regiment of two MAZ-543 and four Al Nida launchers was dispersed in and around the southern city of Amara.

I felt my heart sink; if Hazem Ayoubi’s statements were backed up by contemporaneous unit diaries, Paul’s SCUD “kill” was rapidly losing viability as a story.

The seminar concluded with me reaching across the table and shaking the hand of a man I had come to respect as a true warrior. We may have been enemies during the war, but that fact did not detract from the reality that Hazem Ayoubi had led his men extremely well under the most trying of circumstances.

“Why did you not request this type of meeting with us sooner?” Hazem Ayoubi asked. I told him that I personally had been requesting exactly this kind of meeting since January 1992 but had always been turned down. Hazem smiled. “Well, this was the first time I was aware of your request, and I made sure we honored it. I hope you will put this information to good use.”[19]

We took a break while the Iraqis prepared for the next seminar, which was expected to cover Iraq’s chemical weapons program as it pertained to ballistic missiles. Nikita and I stepped outside, where the burly Russian diplomat lit a cigarette, before asking me what I thought.

“If they produce documents that back their declared missile movements for February 25 and 26, we’re sunk,” I replied.

I saw Paul and Randall across the way, speaking with Larry Chambers, and I waved them over.

“It doesn’t look good for your SCUD kill,” I said.

“We were just talking to Larry,” Paul replied. “We don’t believe a word they are saying. We know what our guys did, and what they personally saw. If you try to give the Iraqis a clean bill of health on accounting based upon this seminar, the US Government will oppose you.”

The Iraqis were watching our little gathering, and something about the way Paul and I were conversing must have made them nervous. Within minutes Hossam Amin, the Iraqi military engineer who served as the Director of the National Monitoring Directorate, or NMD, the organization responsible for overseeing Iraqi compliance with its disarmament obligations and which, by extension, served as the principal interlocutor with the UNSCOM inspection teams, walked up to where Nikita and I were conversing with Paul and Randall.

“His Excellency Amer Rashid would like to speak with you,” Hossam Amin said, addressing Nikita and me.

We followed Hossam Amin down the hall, into the main foyer, resplendent with polished marble floors, Iraqi flags, portraits of Saddam Hussein, and a massive mural showing Saddam at the head of a group of scientists and engineers, with various weapons in the background.

We walked up the stairs, to the second floor. Ahead of us was a long hallway leading to a large office. Armed Iraqi soldiers, wearing the uniform of the elite Special Republican Guard (Saddam’s Praetorian security force), stood watch at the entrance to the hallway, guarding the entrance way to the lair of Hussein Kamal, Saddam Hussein’s all-powerful son-in-law who served as the head of the Military Industrial Commission (MIC), the organization responsible for all of Iraq’s weapons, including those now proscribed by Security Council resolution.

Hossam Amin guided us to the right, down a separate hall, to a door which he opened, revealing the office of Lieutenant General Amer Rashid al-Ubeidi, the Deputy Director of MIC. Amer, a tall, fit man in his early 60’s who had the look of an academic, but carried himself like the General he was, stood to greet us, shook our hands, and then gestured to a sofa in a small reception area which, together with two plush armchairs, surrounded a coffee table. Nikita and I took our seats, followed by Amer Rashid, then Hossam Amin.

“Hossam tells me you had a good meeting with General Hazem,” Amer Rashid said, smiling. He picked up his phone, spoke into it, then hung up. A side door opened, and a young man entered, carrying a tray on which were set glasses of sweet tea infused with lemon, “Basra style”, as the Iraqis called it. Amer Rashid added some sugar cubes from a glass container in the center of the tray, before stirring his glass with a small spoon. He gestured for Nikita and me to do the same, which we did.

Having dispensed with the hospitality required of an Iraqi host, General Amer nodded his head. “What is your impression?” He was looking at Nikita but speaking to me. The Russian diplomat nodded in my direction.

I told Amer Rashid that in my opinion General Ayoubi had provided the inspectors with sound and very convincing information concerning the effect of the air campaign on mobile missile operations. “Much of this information coincides with that available to the Special Commission,” I noted, “a fact which reinforces the credibility of the Iraqi argument that no mobile launchers were destroyed in the course of the war.”

General Amer’s face was lit up with his smile. “Then we are making progress,” he said.

“There is one problem,” I replied. Amer’s features tightened up, and his eyes narrowed.

A week ago, I had accused the Iraqis of lying about having an indigenous manufacturing capability to produce both fuel and oxidizer for its Al Hussein missile force. Like he had done this evening, General Amer had summoned Nikita and I to his office. When I spoke about the calculations regarding fuel usage rates, the General exploded. “Your calculations are killing Iraqi children!” he shouted, slamming his hand on the surface of his desk.

Amer Rashid eventually calmed down and allowed me to walk him through my numbers. He listened intently, and when I finished, sat back dejectedly. “You are correct, Mr. Scott,” he said, addressing me in a fashion common in the Middle East. “We have failed to adequately explain ourselves. We will, and you will see that what we say dos not change the bottom line that we have no weapons of mass destruction remaining. But it is our job to convince you, not the other way around.”

I fully expected another outburst from the Iraqi deputy minister, but instead Amer Rashid looked sad and dejected. “Continue,” he said.

“The Special Commission has in its possession very detailed information concerning the possible destruction of Iraqi mobile launchers during the war,” I said, adding that “the nature of this information is such that the Special Commission cannot simply ignore it.”

“You are being misled by hostile intelligence sources,” General Amer replied, his voice hardening. “They are using you to collect battle damage assessments and other operational data which has no relevance to Security Council resolutions. However,” the deputy minister continued, “I am ready to receive any questions you might have, and I will do my best to get an answer.”

I informed Amer Rashid that much of the discussion between myself and Hazem Ayoubi had been about the issue of “infiltrators”, and that the information in the possession of the Special Commission came from that source.

General Amer nodded his head, and then proceeded to provide a lengthy statement about the role played by “infiltrators” during the Gulf War, as well as the measures Iraq took to defeat them. “These ‘infiltration teams’,” Amer said, “did not even destroy one launcher.”

I told Amer Rashid that the information in my possession suggests, in convincing fashion, just the opposite. “Iraq should concentrate on events taking place in the month of February in and around the Shab al Agharri region of western Iraq,” I added, “between Akashat and Rutba.”

General Amer looked genuinely puzzled. “But General Hazem made it clear that the Al Hussin missile force never conducted any operations in that region.”

I was insistent, however, and soon Amer Rashid, picked up his phone and dialed the number for the General in charge of anti-aircraft defenses in western Iraq. He spoke for a few minutes, raising his voice and moving his hands, before hanging up. We all sat in silence for a few minutes before the phone rang. Amer picked it up and listened, before thanking whoever was on the other end of the line.

“I think we found the source of your information”, General Amer said, smiling. “According to the General I just spoke to, who is in charge for the air defense of all western Iraq, he had a unit of Roland surface-to-air missiles that rotated between H-2 and H-3 airfields.” The Roland system used by Iraq, General Amer noted, were mounted on an 8-wheel chassis which, especially at night, could be easily misidentified as a MAZ-543 TEL.

Sometime in mid-February, General Amer recounted, two of these Roland launchers had been damaged in a coalition air attack. “The launchers were evacuated to a wadi, where a repair crew was dispatched to fix them. After the repairs were complete, the two Roland launchers were dispatched north, toward Akashat. On their way, they were again attacked, with one of the launchers being seriously damaged. The Roland crew moved the launcher into a nearby wadi, where it was again attacked. This time it was destroyed. The commander said he sent a crew to the location to strip the wreckage for salvageable parts, and then the remaining debris was removed and transferred to a military scrap yard.”

Amer Rashid went on to provide more details about other encounters with “infiltrators” in western Iraq. From my perspective, however, the last remaining obstacle to UNSCOM being able to fully assess the Iraqi contention that no mobile launchers or missiles belonging to the Al Hussein Force had been destroyed by coalition action during the Gulf War had been removed.

Nikita and I thanked Amer Rashid for his assistance and made our way back to the first-floor conference room. Paul, Randall, Larry Chambers, and the other American inspectors were gathered in a huddle. Paul saw Nikita and I and broke off, intercepting us before we could join the group. “There’s a mini revolt going on right now,” Paul said. “The feeling is that the Iraqis are pulling the wool over your eyes, and you’re all too happy to accept their stories at face value.”

I shook my head. “What we are doing right now is collecting data. The important thing about this seminar isn’t what the Iraqis have said, but the fact that they have said something on the record. It isn’t a matter of me, Nikita, you, or anyone believing them at this juncture—that’s not the mission. The mission was to collect data that we can take back with us and do a detailed assessment as to whether the Iraqis are telling the truth. There’s no wool being pulled over anyone’s eyes.”

Paul pondered what I said for a minute, then asked “So what was the meeting with Amer Rashid about?”

“Nothing that will make you happy,” I said. I relayed to him the information about the Roland mobile launcher, and the possibility that what we had here was more a case of mistaken identity than confirmed kill.

“I’m going to go inform the guys,” Paul said.

I watched as Paul walked back to the huddle, and then pulled Randall aside. As Paul talked, Randall became visibly agitated. Clearly the information I had given Paul was not going over well. Paul and Randall moved on to the huddle, where the information didn’t go down any easier for the second telling. The group dispersed and made its way back into the conference room, where the chemical weapons seminar was about to begin. Paul walked over to Nikita and me. “They’re not buying it,” he said.

“I’m not asking them to,” I relied. “If they aren’t convinced, then they need to put some data on the table of their own that explains why.”

“That’s not really the point anymore,” Paul said.

I shot Paul a puzzled look. “What do you mean by that?”

Paul laughed. “The Iraqis told a good story. It is going to be hard to refute it. Hell, maybe we can’t. Maybe the Iraqis are telling the truth. But that’s not a narrative that Washington, DC appears to be willing to embrace. Medals were awarded for killing SCUDs. Careers have been built on the perception of a victory that includes our team destroying their missiles. That narrative is not going to change. These guys,” Paul said, nodding in the direction of his fellow American inspectors, “are going to go home and try and sabotage this inspection. They will attack the data collected. They will attack Nikita,” Paul said, now nodding at the Chief Inspector, “for being Russian. And they are going to attack you for having gone soft, for being more ‘light blue’ (the color of the United Nations flag) than ‘red, white, and blue’. It doesn’t matter if none of it is true. It’s just the way it is.”

Paul laughed and shrugged his shoulders. “I think we can declare the SCUD hunt over from a practical point of view. The war is over. What happened, happened. We are about to enter a new phase, one where facts no longer matter, only perception. It is about to become a battle of political will. I don’t envy you.”

The UNSCOM 45 inspection was conceived as the culmination of a campaign that had been ongoing since December 1991, when UNSCOM carried out is first inspection-based SCUD hunt. That inspection, which had been foisted on UNSCOM by the Americans, had been a fiasco. Since then, Nikita and I had worked together to put together a series of inspections intended to compel Iraq to, literally, come to the table and be open about the truth regarding their missile programs. We had just accomplished that. Apparently, that wasn’t good enough for my government.

It was now clear to me that if I wanted to continue down the path of finding out the truth about Iraq’s ballistic missile capabilities, I was going to have to be prepared to fight a two-front war. The primary objective continued to be pressing Iraq to fulfill its disarmament obligation by providing UNSCOM with verifiable fact-based information that could be used to sustain a finding of compliance. But a second front was now opening, a war of disinformation being waged by the United States that sought to denigrate both the Iraqis and the UNSCOM inspectors.

Paul was right—a new phase of the SCUD Hunt was starting, one I feared would have me in conflict with my own government as well as the Iraqis when it came to discerning the truth about the Iraqi SCUD missile force.

To get to the truth, however, one needed to back in time, to where the story of Iraq’s SCUD missile force began.

[1] Author conversation with Delta Force officer.

[2] Buck Wyndham, Hogs in the Sand (Koehler Books: Virgina Beach, 2020), p. 311.

[3] Author conversation with Delta Force officer.

[4] Author conversation with Delta Force officer.

[5] Wyndham, p. 311.

[6] William L. Smallwood, Warthog: Flying the A-10 in the Gulf War (Potomac Books: Omaha, Nebraska, 1998), p. 198.

[7] Wyndham, p. 312.

[8] Douglas Waller, Commandos: The Inside Story of America’s Secret Soldiers (Simon & Schuster: New York, 1998), p. 348; Author conversation with Gary T., December 13, 1991.

[9] Waller, Commandos, p. 348.

[10] Wyndham, pp. 311-312.

[11] Wyndham, p. 312.

[12] Wyndham, p. 312.

[13] Wyndham, p. 312.

[14] Author conversation with Delta Force officer.

[15] Personnel from Delta Force often operate using false names when interacting with organizations such as the UNSCOM. The names used here represent the identity adopted by these two during their work with UNSCOM and are not their real names.

[16] Ar’ Ar’ is a small Saudia Arabia town located near the Iraqi border. During Desert Storm Delta Force, together with other Special Operations forces, used the small civilian airport which served Ar’ Ar’ as a forward operating base.

[17] UNSCOM 45 Report, Annex Z, pp. Z-5-16, 17.

[18] UNSCOM 45 Report, Z-5-15.

[19] UNSCOM 45 Report, Z-5-35.

Thank you, Scott! Great lessons here, well done!

I congratulate you Scott. Immaculate facts, dates, diagrams, photos. You at the back tallest, longest legs, as ever. OK,OK I'm a shorter (though beautifully formed) Brit. No jeans Mr Levi ever made fit me, and I'm therefore just a tad envious. I'm going to by the Scud hunter book, very best Dr Jo East Anglia

Ps I have ...Perestroika and Road to

Hell. Really appreciate Clarity Press production standards.