The Battle of Riyadh

Israel had been hit hard by SCUDs for two straight days. Our turn came on January 20, when a total of eight SCUDs were launched against targets in Saudi Arabia, including four toward Riyadh. This feat was accomplished only by the tenacity and audacity of the men of the Al Hussein Force. Following the second strike against Israel, on the morning of January 19, General Ayoubi ordered that all launchers designated to participate in the planned attack on Saudi Arabia should return immediately to the filling and arming site at Ramadi, where they would be loaded with a combat ready missile before proceeding south.

This was a very tricky operation, as it involved dispatching fully loaded missile launchers down a major highway during daylight hours in the middle of a war where enemy aircraft were actively searching for this very activity. The launchers, with sufficient intervals, proceeded from one hide location to the next, which they would not depart until the ‘all clear’ signal had been given by air defense, which monitored the skies above for hostile aircraft. In this way, both Unit 224 and Unit 223 were able to be in position to fire a total of six missiles at targets in Saudi Arabia on the night of 20/21 January.

For the attack on Riyadh, General Ayoubi had allocated six launchers from Unit 224, operating in the vicinity of the southern Iraqi town of Safwan. At 9 pm on January 20 two of these were able to launch their missiles; one of these was the 10th battery. As soon as they finished, several of the Unit 224 MAZ-543 batteries, including the 10th, immediately headed back north to Baghdad, and then Ramadi, where they were reloaded with missiles to continue their attacks against Israel.

I was in my quarters in Eskan village when the air alarm went off, warning of the incoming missiles. Like everyone else in the apartment complex, I donned my MOPP (Mission Oriented Protective Posture) gear, which consisted of a gas mask, charcoal-lined overgarments, rubber gloves and over-boots. Not satisfied with sheltering in place, as required by our standing orders, I made my way to the roof of the apartment to see the action taking place outside; I justified this insubordination by labeling my actions as a “necessary intelligence gathering function.”

Within seconds of my arrival, I was able to make out the orange glow of a SCUD burning off its residual fuel as it completed the final leg of its ballistic trajectory. I was startled by a Patriot battery which fired its missiles from a position close by. The S-shaped trajectory taken by the Patriot PAC-2 missile as it adjusted to the trajectory of the SCUD missile projected by its acquisition radar had it fly dangerously close to the ground, passing right over my head before climbing into the sky toward the SCUD.

I could see at least three explosions in the sky as the Patriot missiles appeared to intercept the SCUD, followed moments later by a larger explosion on the horizon as the SCUD warhead impacted the earth. This experience was repeated a second time when another SCUD streaked across the night sky, prompting a second salvo of Patriot missiles, more airborne explosions, and another large detonation on the ground. These missiles both struck Riyadh; an impact outside an office building produced a 10-foot-deep crater and knocked down a portion of that structure, injuring a dozen people. One of the Patriot missiles launched to intercept these SCUDs, however, ended up hitting the ground in Riyadh as well; it is not known if the crater was caused by a SCUD or a Patriot.[1]

In the aftermath of the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, in August 1990, General Schwarzkopf requested that a Patriot air defense capability be among the first US forces to be deployed into Saudi Arabia. The 11th Air Defense Artillery (ADA) Brigade, commanded by Colonel Joseph Garett III, was tasked with providing a Patriot battalion. At the time, the only interceptor missiles available to the 11th ADA were what the Army called “Patriot Advanced Capability, Phase 1”, or PAC-1, variants. The PAC-1 was a modification of the original Patriot surface-to-air missile, a 1970’s-era missile designed to shoot down waves of Soviet aircraft in any large-scale European conflict.

Patriot was originally deployed to the 32nd Air Defense Command, subordinated to US Army, Europe. Faced with a capable Soviet tactical ballistic missile threat, the US Army modified the original Patriot tracking system, along with the interceptor missile’s fusing and warhead, for the purpose of achieving a so-called “warhead kill”—using the explosive power of the Patriot to knock an incoming missile off course, and thereby preventing it from hitting its intended target. Initial tests of the PAC-1 interceptor were conducted in 1986, and by 1988 the PAC-1 interceptor was deemed operational.

As the Soviets improved the performance of their tactical ballistic missiles, so, too, did the US Army seek to keep pace by developing improvements to the PAC-1 system. By August 1990 the Army was finalizing preparations to test a new missile interceptor, the PAC-2, which incorporated new software, fusing, and warhead components designed to generate a “hard kill” capability.

The operational history of the Patriot missiles did not get off to an auspicious start. Around 4 am on January 18, while Israel was being pummeled by Iraqi missiles, First Lieutenant Charles McMurtrey and Sergeant Joe Oblinger, both assigned to Alpha Battery, 2nd Battalion, 7th Air Defense Artillery Regiment, 11th Air Defense Brigade, responsible for defending the US Air Base at Dharan, Saudi Arabia, were standing duty, scanning the radar screens for any sign of a hostile attack, when suddenly their green-lit electronic display indicated that a single missile was inbound.

“I knew right away what it was,” McMurtrey recalled afterwards. “There’s no way you can confuse it.”

The battery commander, Captain Jim Spangler, alerted the battalion command post, which activated a siren, followed by an announcement: “Condition Red, Condition Red, don your gas masks!”

In the firing battery command van, the operators stood by as the Patriot system, operating in automatic mode. At 4.28 am, the battery fired two PAC-2 missiles, which arched upwards in the early morning sky, maneuvered twice, before exploding. “I was standing outside my tent about three kilometers away”, Lieutenant Colonel Leeroy Neel, the battalion commander, recalled. “I saw the explosion, but it didn’t register immediately. Then I thought, “my God, that’s one of mine.’”

The lack of any battle damage reports did not faze Neel. “A chemical team takes care of that,” he noted. “My people just find them and shoot them down.”[2]

For Neel, Spangler, McMurtrey, Oblinger, and the rest of the personnel of Alpha Battery, the Patriot missile had just completed its combat initiation with flying colors.

Later that evening, it was Bravo Battery’s turn. Once again, the tactical control officer on duty informed the battery commander, Captain Joe DeAntona, that his radar was tracking an incoming SCUD. As with Alpha Battery, the Patriot system operated by Bravo Battery was on automatic mode. DeAntona gave the order to engage, and almost immediately two PAC-2 Patriot missiles were fired into the night sky. Shortly afterwards, the system reported that the target had been destroyed.

“It was high-fives and loud clapping,” DeAntona recalled. “It was like a game-winning shot, it was like scoring the winning touchdown pass on the last play. It felt like victory.”[3]

DeAntona’s troops, however, were not celebrating victory, but rather a glitch in the Patriot system that had resulted in the launching of PAC-2 interceptor missiles against phantom targets. The celebrated first “successful engagement by an Air Defense system ever in combat history” was, literally, nothing more than a ghost in the machine, the product of what the Army later called “significant frequency overload” caused by the powerful electronic signals generated by the radars and jammers of systems such as the E-3 Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS) and EF-111 Raven which resulted in the Patriot radar generating false tracks which the system, when in full automatic mode, then responded to as if they were real.[4]

Over the course of the next few days, Iraq sustained its barrage of missiles, hitting Israel and targets throughout the Arabian Peninsula on a near daily basis. Aircraft which were tasked with striking non-SCUD targets in Iraq were diverted to join in an expanding counter-SCUD mission that was proving to be vexing from a BDA standpoint.

“These attacks,” General Khaled Bin Sultan, the Saudi Commander of Joint Forces, recalled afterwards, “prompted us to think of retaliation.”[5] Saudi Arabia had in its possession a force of between 36 and 60 Chinese-made DF-3A medium range missiles which had been purchased in great secrecy in 1986, and which limited operational capability in 1989. The Saudi decision to procure these missiles was founded in the missile war being waged at the time by Iraq and Iran. The best way to deter any regional power from firing missiles at Saudi Arabian cities, the Saudi leadership believed, was to have its own missiles available for immediate and devastating retaliation. The Saudi operation to acquire and field the DF-3A was known as the East Wind.

With a range of 1,646 miles (2,650 km) and a payload of around two tons, the DF-3A was the most potent missile in the region at the time, except for Israel’s nuclear-tipped Jericho 2. During the planning for the opening night of Desert Storm, the DF-3A had been incorporated into the initial attack, with a dozen or so missiles to be fired at Iraqi SCUD-related targets. However, the Saudi’s balked at the last second, concerned over the optics of having an ostensible defensive weapon of retaliation employed offensively in a pre-emptive strike.

The Iraqi missile attacks, however, changed everything. General Khaled Bin Sultan ordered the commander of the Saudi Missile Forces, Brigadier General Ibrahim al-Dakhil, to prepare several missiles for launching against several key Iraqi cities to deter future attacks. The missiles were made ready save for the loading of the volatile liquid fuel; once a missile was loaded with the highly corrosive fuel and oxidizer, the missile either had to be fired immediately or else taken out of service for repair.

Once the missiles were ready, General Khaled Bin Sultan notified the Saudi leadership and awaited the orders to fire. These orders never came. The Saudi ruler, King Fahd, had decided that the DF-3A was a weapon of last resort and, as such, would not be used to retaliate against further Iraqi missile attacks. One of the factors that weighed in on this decision was the fact that the DF-3A was, if anything, even less accurate than the Iraqi Al Hussein missiles, and by launching two tons of high explosives against Iraqi cities, Saudi Arabia would be guilty of the same charges of indiscrimination and hazarding of civilian life and property as were being levied against Iraq.[6]

A few days after the initial SCUD attack on Riyadh, on January 23, a team of missile experts from the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) flew into Riyadh to conduct a technical analysis of the missile debris that had been recovered from the initial attacks. In my role as the SCUD BDA officer, I was invited to participate in the final debriefing session. I knew several of the DIA team from my time as an INF inspector, and the debriefing quickly took on the air of a reunion. Other analysts included two from the US Army’s Missile and Space Intelligence Center in Huntsville, Alabama named Curtis Gentry and Gail Shephard, who were to become close colleagues of mine in the years to come.

The SCUD missile had been produced by the Votkinsk Factory at its downtown facility, Plant 235, a fact I mentioned in passing. Some of the CENTCOM officers present were surprised to hear about my experience as an INF inspector, and my service at the Votkinsk Portal Monitoring Facility. I even mentioned that I had met some of the Soviet workers responsible for building the SCUD. There were a lot of assumptions being made as we discussed the technical features of the Iraqi missile, with some of the CENTCOM contingent wrongly concluding that I had inspected SCUD missiles at Votkinsk, instead of SS-25’s. This error would prove consequential in the days to come.

The briefing turned out to be quite informative. The Iraqi version of the Soviet SCUD, which they called the Al-Hussein, was basically an elongated missile made by cutting up two SCUD missiles to make larger fuel and oxidizer tanks, before rewelding the pieces back together. The warhead had been reduced in size from 985 to 500 kilograms (2,170 to 1,100 pounds) of high explosive, a factor which, when combined with a longer burn time brought on by the increased fuel, extended the range of the missile from to approximately 650 kilometers, or 400 miles.

While the official CENTCOM position was that all incoming Iraqi SCUDs had been successfully intercepted by the Patriot PAC-3 missiles, the debris told another story—the elongated Iraqi missile was subjected to greater amounts of structural stress produced by the higher speeds achieved through the longer engine burn time and distance of travel. As a result, the airframe tended to breakup in the final phase of the flight into three sections comprising the engine compartment, the fuel tanks, and the warhead and guidance sections. The larger of these three was the section comprising the fuel tanks, and it was on this piece that the patriot missile would aim, leaving the warhead section to spiral to the earth unmolested.

The fact of the matter was that the Patriot missile was not preventing the modified SCUD warhead from reaching its target, which explained the large crater in downtown Riyadh that no official would admit was produced by a SCUD lest they undermine the Patriot missile success narrative that had been constructed.

I came back from the DIA technical debriefing convinced more than ever that the Iraqis were winning the missile war. Not only were they launching missiles with impunity, but by happenstance the structural deficiencies inherent in their modified Al-Hussein missiles served to create de facto decoy objects that facilitated their warheads penetrating the Patriot missile shield. Only the massive inaccuracy of the missile, with a circular error of probability of up to nine kilometers (5.6 miles), prevented greater casualties.

This was war, and although the BDA cell was organized to work in rotating shifts, I never returned to my quarters directly after being relieved. I would instead pour over intelligence reports, trying to find something that could help turn the tide in our favor against Iraq. This included going over to the Combat Camera office, where I had requested the airmen working there to assemble a videotape containing all the days reported SCUD kills for my review. I would then spend hours examining these images, looking for anything that would sustain the claimed result. In every instance, I was compelled to dismiss the reported kill as unfounded, even though every fiber in my being wanted a different result.

I was responsible for producing a daily tally of confirmed SCUD battle damage, a list that had taken on enormous political importance with Israel demanding to be allowed to send its Air Force into western Iraq to do what the US Air Force had so far been unable to accomplish—kill Iraqi SCUDs. It was not as if the boys in blue were not trying; another document which had taken on political importance was the daily diary of counter-SCUD activity, detailing each mission flown in the counter-SCUD effort.

Kill Saddam

My war took an interesting turn during the evening of January 24 when Lieutenant General Calvin Waller, the Deputy Commander of CENTCOM, burst into the BDA cell, proclaiming loudly, “Where’s that Russian missile expert?”

Everyone in the room looked toward me, and I stood up. “I guess that would be me, Sir.”

Waller did not mince words. “Come with me. I have a job for you.”

We took the elevator from the basement to an upper floor in the MoDA headquarters building. “You’re going to be meeting with Prince Turki Bin Faisal al Saud, the director of al-Mukhabarat al-A’amah (the Saudi General Intelligence Directorate).”

Prince Turki was the eighth and youngest son of King Faisal and had been the head of intelligence since 1979. “This is a big deal. The Saudi’s are genuinely concerned about the missile threat posed by Iraq. Right now, we are not doing a particularly good job at stopping the SCUDs from hitting Saudi Arabia. We need to be doing something positive. The prince has an agent inside Iraq and has informed us that he has some intelligence about Iraq’s missile program. This is the first time the prince has shared this kind of intelligence with us. I think it’s a test of our ability to respond to intelligence of this sort.”

General Waller paused and looked at me. “Don’t fuck this up.”

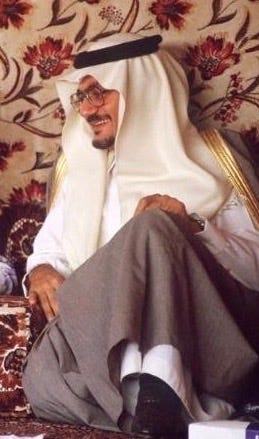

The General and I were ushered into a dimly lit room lavishly outfitted with fine furniture, including a sofa that we were directed to sit in by a man dressed in elegant white Arab garb, inclusive of khafiya. Soon after we were seated, another man entered the room—Prince Turki, similarly clad as his attendant, with the addition of a black bisht, or robe, made from finely woven wool trimmed in gold embroidery. General Waller and I stood as the prince made his entrance, sitting only after he had taken his seat in a chair opposite us.

This was my first experience with Arab nobility and the art of the drawn-out conversation. I was accustomed to getting straight to business, but clearly this was not the Saudi way. I sat in silence as General Waller and Prince Turki engaged in polite conversation, only nodding my head when the General introduced me as the “the missile guy”. Rich aromatic Arabic coffee was served, along with dates. I sipped my coffee only after the Prince and General Waller sipped theirs, and similarly took a single date only when each of my seniors had done the same.

After what seemed an interminable wait, we finally got down to business. Prince Turki raised his hand, and a Saudi officer entered the room. The prince introduced him as an intelligence officer who ran several human sources inside Iraq. According to the Saudi intelligence officer (who spoke Arabic, with Prince Turki translating), recently an Iraqi source had submitted a report about preparations being made to use a new kind of missile against Saudi Arabia. This missile was believed to use solid fuel, and had a longer range, greater payload, and more accuracy than the extended SCUDs that had been used by Iraq thus far in the war. The missiles had been prepared in a hardened bunker. The source noticed that the floor of the structure where the missiles had been worked on was covered in a granular white powder.

The Saudi government was concerned about the possibility of this missile being used against Saudi Arabia and was hoping that CENTCOM would be able to provide some insight into what kind of missile the Iraqi source was speaking about.

I asked the prince if I could have a day to prepare an assessment. He said yes, and General Waller and I were escorted from the room. On the way back down to the basement Waller was silent. When the elevator door opened on the CENTCOM workspaces, he turned to me. “Let me know when you have something for the prince,” he said, before leaving me for the sanctum of the Combat Operations Center. There was no fanfare, no pep talk—nothing.

I went to the Current Intelligence Center (CIC), where I started digging through intelligence reports. I found one dated back a few years which claimed the Iraqis had received some SS-12 medium-range missiles—another Votkinsk product—from the Soviets in the mid-to late-1980’s. I also found a report prepared by DAT-6, the office in the Defense Intelligence Agency responsible for attaché operations in the Middle East/North Africa, which investigated this very report, concluding that such a transfer had not occurred.

The SS-12 was one of the missile systems banned under the terms of the INF Treaty. I recalled that in February 1990 the US had learned that several SS-23 short-range missiles—which like the SS-12 had been banned by the treaty—had been transferred to East Germany, Czechoslovakia and Bulgaria before the treaty went into force, and subsequently not declared by the Soviet Union. I wondered if it were possible that the Soviets, in similar fashion, had transferred some SS-12 missiles to Iraq, and just not told anyone.

The SS-12 used the same MAZ-543 TEL as the SCUD, which would make such a limited transfer even more difficult to detect. CENTCOM had little intelligence on the SS-12 beyond that one report, which was several years old, and the DAT-6 investigation, which was dated December 1990. I could submit a request through channels to speak with the report’s author to get clarification, but that would take days—time I did not have. Instead, I decided to reach back into my recent past for answers.

I placed a secure call to operations room of the On-Site Inspection Agency (OSIA, the Department of Defense agency responsible for implementing the provisions of the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces, or INF, treaty), identified myself by name, and asked if I could speak to someone familiar with the SS-12 missile system. Within a few minutes I was talking with Lieutenant Colonel Tom Brock, one of the Inspection Team Leaders. I filled him in on the nature of my request and asked him if there was any possibility that some SS-12 missiles could have been transferred to Iraq by the Soviets before the INF Treaty was signed. Tom asked me to give him a couple of hours to run this question down. When I called Tom back, he informed me that he had discretely reached out to the Soviets and asked my question and had been assured that no SS-12 missiles had been transferred to Iraq, or any other non-Soviet entity. All SS-12 missiles were scheduled to be destroyed under the INF Treaty.

I next turned to other potential sources of solid fuel missiles that the Iraqis could be using. Intelligence reports spoke of an Argentinian missile, the Condor II, that had been developed in conjunction with the Egyptians as the Badr-2000, who subsequently sold the designs and technology to the Iraqis under the same name. The Iraqis had constructed a modern facility southwest of Baghdad known as Taj al-Marik where the Badr-2000 was to be produced. All indications were that this effort had not reached fruition by the time the war had started. It was unlikely that the Badr-2000 was the missile which the Saudi intelligence source was referring to.

I could come up with no other plausible scenario where the Iraqis could have either acquired an operational intermediate-range solid fuel ballistic missile, or manufactured one indigenously, with or without outside held. I checked the BDA data base and found that Taj al-Marik had already been struck several times and was considered to have been either destroyed or neutralized (indeed, the air strike on Taj al-Marik, consisting of a score of Tomahawk cruise missiles, nearly succeeded in killing the Deputy Director of MIC, Amer al-Sa’adi, who was, like Amer Rashid at Taji, conducting a tour of the facility to ascertain how much damage had been done a a result of coalition attacks.)

Based upon this assessment, I was satisfied that Iraq did not have a solid fuel missile capable of threatening Saudi Arabia. I wrote a two-page memorandum for General Waller detailing my reasoning, which I delivered to him personally the next morning.

That evening I was summoned back to the Combat Operations Center, where I found General Waller waiting for me, holding my report in his hand. “The prince will see us now,” he said.

The meeting unfolded in precisely the same manner as the prior evening. Once the coffee had been drunk and the dates eaten, General Waller handed my report to Prince Turki, who received it and put it down on the table without looking at it. “I would like to hear from your expert in person,” the prince said.

I briefed him on the contents, as well as my conclusion—the intelligence was wrong, and there was no threat to the Kingdom from a new Iraqi solid fuel missile. The prince translated my words to the Saudi agent handler, who listened without any expression or reaction. Prince Turki thanked me for my work, and once again General Waller and I departed for our basement offices. The General was visibly relaxed—clearly the meeting had gone well from his point of view. As for me, I was glad to have been of service.

General Waller called on me one more time, in the afternoon of January 27. “The prince wants to see you,” he said. “Apparently you impressed him.”

In a scene that was a repeat of the first two, Prince Turki, accompanied by a Saudi agent handler, briefed General Waller and I on sensitive human intelligence from a Saudi spy operating inside Iraq. “Saddam Hussein is planning on visiting Basra on January 30 to meet with his commanders. He will arrive sometime on the 29th and will be staying in the home of a prominent local citizen.” Prince Turki went on to provide a description of the building and its surrounding environs, which I wrote down.

The prince stopped speaking, and I looked over to where General Waller sat. “Your job,” General Waller said, “is to locate the building in question and turn it over to the Air Force for targeting.”

Prince Turki thanked us before departing, leaving General Waller and I alone in the room. “We’re going to kill Saddam?” I asked. “Isn’t that assassination?”

General Waller gave me a hard stare. “It’s a leadership target,” he said, his voice firm. “We are at war. Saddam is going to be planning operations designed to kill Americans. This is our chance to stop him.”

As far as I was concerned, I had just been given a lawful order.[7]

I turned to the professionals at the Joint Imagery Production Complex (the Desert Gypsy) for help. The JIPC conducted first-phase analysis of national, theater and tactical imagery from a variety of sources. “First-phase analysis” is defined by doctrine as “the rapid exploitation of newly acquired imagery and reporting of imagery-derived information within a specified time from receipt of imagery” and satisfies “priority requirements of immediate need.” General Waller had made it clear to me that killing Saddam was a “priority requirement”, and the resources of the JIPC were put at my disposal.

The JIPC was set up in a cluster of tents and shelters located in Riyadh International Airport. I took a shuttle to the airport, where I was greeted by an Army Colonel, the JIPC commander, who had been alerted to my arrival. After I laid out the gist of my problem, he turned me over to a female airman whom he said was his top photographic interpreter. Given the time constraints involved, the plan was for the airman to do a survey of existing satellite imagery, trying to isolate possible candidates, before tasking satellites to take current imagery. The fact that we had been given the ability to task a national resource was a big deal—due to limited satellite availability, the JIPC was limited to only 50 frames of digital satellite imagery per day. We were in the middle of a war, where the competition for satellite tasking was tremendous. It became clear to me that killing Saddam was a high priority task.

I left the airman to do her job. She would call me at my desk when she had identified candidate locations.

The phone call came the next evening. Time was short—I needed to get some target grids over to General Waller soon if he was going to be able to get them into the Air Tasking Order for the night of 29/30 January. The airman had done a remarkable job turning my verbal description into actual targets on the ground. She had identified six potential candidate locations, three of which she deemed to be a close fit.

That evening the airman and I were in the middle of studying the imagery—taken earlier that day—through specialized devices that produced a 3-D image. Just before 9 pm, the air raid alarm went off, signaling an inbound SCUD. While we did not know it at the time, the 19th battery, operating near Safwan, had fired a single Al Hussein towards Riyadh.

The airman laughed. “I guess Saddam heard about us,” she said, “and is trying to get us before we get him!”

The Colonel stuck his head into our workspace. “Mandatory evacuation to the air raid shelter”, he said. “Masks on.”

“I’m running out of time, Sir,” I said. Experience showed that anywhere from 45 minutes to an hour could pass between the sounding of an alarm and the all-clear signal. I still needed to decide on which targets to pass to General Waller. “I’m staying.”

He did not argue. “It’s your funeral.” But when the airman (to her credit) also volunteered to remain behind to help me, the Colonel drew the line. “You work for me. He doesn’t,” the Colonel told her. “Get going.”

In the background I could hear Patriot missiles firing, followed by the explosion of the SCUD warhead impacting the ground. “You missed, you Bastard”, I muttered, knowing well I was not the target and, moreover, if I had been, the poor accuracy of the Al Hussein all but guaranteed my survival.

This did not mean the missile was harmless; Newton’s universal theory of gravity— “what goes up must come down”—meant that the SCUD warhead was going to land somewhere. On this night that “somewhere” was a populated area of Riyadh, doing considerable damage. The fact that it was obviously not a chemical munition helped speed up the all-clear signal, and soon the airman was back at her workstation. By then I had narrowed it down to three targets, which I had prioritized in terms of probability. I asked the airman for her opinion, and after carefully examining each image, she agreed.

I had my targets.

I returned to the MoDA building, and reported to the Combat Operations Center, where General Waller sat, running the war. I was escorted in, and walked up to the General, handing him an envelope with a single sheet of paper on which were typed the grid coordinates of each target.

“Are you sure about these?” he asked.

“As sure as I can be based upon the information provided,” I responded. “These are the top three locations in the Basra area that fit the description provided by Prince Turki.”

General Waller thanked me, and I was ushered out.

I learned later that two of the targets were bombed by F-111F aircraft on the day Saddam was supposed to be travelling. The reports, however, turned out to be false — Saddam never travelled to Basra. The buildings hit were most likely civilian homes. I do not know what, if anything, became of the occupants of the two buildings that were struck, but I do know they were deemed to be occupied at the time they were designated as targets, and 2,000-pound bombs are not known for their soft touch.

The Black Hole

By January 23 it was obvious to everyone that the United States, despite all its many assurances to the contrary, did not have a solution to the Iraqi SCUD problem. The pressure inside Israel was building for retaliation. The domestic political tension was furthered by some inopportune comments made by General Schwarzkopf to BBC radio about the threat posed by the Iraqi missiles. “Saying that SCUDs are a danger to a nation is like saying that lightning is a danger to a nation,” Schwarzkopf noted. “I frankly would be more afraid of standing out in a lightning storm in southern Georgia than I would standing out in the streets of Riyadh when the SCUDs are coming down. If it’s going to hit you it’s going to hit you, but the percentages are so much less.”[8]

It was left to others to do damage control. Major General Armstrong had to assuage the leadership of the Israeli Defense Force (IDF), who emphasized the hair-trigger nature of their retaliatory force, and the fact that they were under increasing criticism from their own citizens for not pulling it. In private, however, these same IDF officials—especially those from the Israeli Air Force—admitted that they did not have a better solution to finding and killing the Iraqi mobile SCUDs than what was currently being done by the American-led coalition forces. The issue, however, was not one of military practicalities, but rather domestic political reality—the IDF plan would be implemented if the political pressure continued to mount, and this pressure increased with each SCUD attack from Iraq.

What the IDF leadership needed from Major General Armstrong was detailed information which highlighted the US actions in western Iraq so that they might forestall any rash action by their own political leadership. In particular, the IDF requested advance knowledge of what targets were being struck, assurance that there was an active counter-SCUD presence over western Iraq, and timely battle damage assessments. All of this would considerably aid the IDF in placating Israeli political concerns that everything was being done that could be to stop the Iraqi SCUD attacks. Major General Armstrong passed on the Israeli request to Central Command headquarters in Riyadh.

While Major General Armstrong was meeting with the IDF in Tel Aviv, the battle damage analysts at CENTCOM J-2 were beginning to come to grips with the scope of the failure of the US-coalition air strikes against the Iraqi mobile SCUDs. As the lead SCUD battle damage assessment analyst, I played a major role in this effort. In a blunt assessment, I highlighted the fact that while nearly 40% of the air strike missions flown by US-coalition aircraft between 20-23 January had been targeted against the mobile SCUD threat (in both western and southern Iraq), the actual damage inflicted was, to be blunt, negligible. The pilots flying these missions had reported over 60 mobile SCUD launchers destroyed by 23 January; CENTCOM pre-war estimates credited Iraq with only 26 mobile launchers, and DIA’s estimate—historically inflated—listed Iraq as having 36 mobile launchers.)

According to the pilots, we had killed twice as many mobile launchers as we believed the Iraqis could possess. And yet the SCUD attacks continued. The bottom line was that, despite the considerable amount of effort being placed on locating and destroying the Iraqi SCUD force in western Iraq, on the eve of an urgent Israeli request for information and data needed to prevent the conflict from spreading, the United States had very little of substance to report. CENTCOM’s quick little 48-hour campaign to rapidly destroy Iraqi SCUD missiles deployed against Israel had failed, and now the United States was being called to task.

The CENTCOM response was to turn to the Air Force—Lieutenant General Horner and his strike planner, Brigadier General Glosson—for a solution. The irony in this choice was thick, as it was this pair which was primarily responsible for the predicament the United States now found itself in. Moreover, nothing in the events of the past days suggested that either of the Generals had undergone a transformation concerning their strategy for coping with the mobile SCUD threat.

Brigadier General Glosson’s strike planning cell (the so-called Black Hole), were deeply involved in charting the progress of their Air Tasking Order (ATO), which many in the cell felt to be beyond reproach and thus unalterable. In the opinion of these planners, the ATO was designed for the purpose of liberating Kuwait, not defeating a mobile SCUD threat. The fact that the introduction of Israeli combat forces into the war because of the Black Hole’s failure to find a solution to the SCUD problem would lead to the disintegration of the coalition and the failure of the entire campaign was, to these planners, a political problem, not a military one.

One of the major reasons the Black Hole took the stance they did was that they were tasked with implementing a strategic air campaign designed to defeat the nation of Iraq, not orchestrate a tactical battle against mobile missiles. The processes involved in putting together and executing this strategic campaign were as complex as they were time consuming. The normal mission planning cycle involved in putting bombs on target was a three-day process. Using a target list produced well in advance, the Black Hole planners produced what was known as the master attack plan (MAP) on day one. Here the various targets to be attacked in a 24-hour period would be presented, in order of priority.

On day two, the Guidance, Apportionment, and Targeting Division (GAT) would transform the MAP into the actual air tasking order (ATO) by identifying a specific aircraft and bomb type for every point on the ground designated to be attacked. The ATO would be entered into what was known as the computer-aided force management system, or CAFMS, an interactive computer-based platform used to relay information and facilitate text-based discussion between users. This was how the strike packages were disseminated to the operational squadrons. If the mission planners at the squadron level had any questions or concerns, they would use the CAFMS to communicate with the Black Hole for clarification. If everything checked out, the actual bombing missions would be flown on day three.

The strategic air campaign was designed to unfold over the course of weeks, with a synergism produced by a specific sequencing of targets over time. It was a living, breathing reality, a finely tuned system dedicated to implementing the plan as it existed, and not shooting from the hip. There was an ability to make small adjustments as targets of opportunity came up—my targeting of Saddam Hussein based upon Saudi human intelligence serves as a case in point. But as far as the Black Hole was concerned, the ATO had already accounted for the Iraqi SCUD problem with its 48-hour plan of attack. It was time to get on with fighting—and winning—the rest of the war.

According to the initial estimates prepared by the Black Hole, the sortie rate (with one sortie representing the launching and recovery of a single aircraft) for phase one of the strategic air campaign was supposed to have levelled out at approximately 100 sorties per day by day seven of the campaign (D+7). The sortie rate had instead soared to over 1,200 sorties per day, with a significant portion of these (some 40%) being flown in support of the unplanned counter-SCUD effort. The Black Hole rightfully believed that the tempo of the ATO was being put at risk, and with it the timing for the entire Theater Campaign Plan—in short, if things kept going the way they were, the ground attack to defeat the Iraqi army and liberate Kuwait would have to be delayed.

The Black Hole believed that a balance needed to be struck between achieving the main objective of the Theater Campaign Plan (the liberation of Kuwait) and the appeasement of Israeli political concerns. The thought of reapportioning valuable air assets based upon political issues rankled the planners, especially their leader, Buster Glosson. The counter-SCUD effort had already denied the Black Hole planner the precision strike capability of the F-15E Strike Eagles of the 335th (Chiefs) and 336th (Rockets) Tactical Fighter Squadrons and threatened the sustainability of the overall air campaign by throwing off logistical and maintenance time schedules. If this trend continued, the Black Hole believed, it could cripple the overall US Air Force war effort. From the perspective of the Black Hole, the Theater Campaign was not to be disrupted any further, Israeli concerns be damned.

Logistics

While Desert Storm officially began on the night of 16/17 January, Unit 224 had been on a war footing since March 1990, and the wear and tear of near-continuous operations had taken its toll on the ageing vehicles, especially the MAZ-543 launchers, which were built back in 1974, and had already been through eight years of combat service in the Iran-Iraq War. On the first night of operations against Israel, one launcher—the 5th battery—broke down and was unable to launch, while another—the 1st battery—successfully launched its missile, but then was taken out of service for repairs. The 5th battery was able to participate in the second night’s attack, but then broke down again. Both the 1st and 5th batteries were pulled out of service for repairs and were not able to make the move to the south, and as such missed out on the opening salvo of Al Hussein missiles fired into Saudi Arabia.

Problems continued to plague the mobile launchers of Unit 224. While both the 2nd and 7th batteries were able to participate in the opening attack on Saudi Arabia, they, too, suffered malfunctions that required them to be withdrawn back to Baghdad for repairs, even as the 1st and 5th batteries were brought back up online.

That any of the worn-out launchers remained operational at all was only through the hard work and heroic efforts of the men of the Unit 224 Technical Battalion who, along with the missile technicians of the First Maintenance Unit, made sure that maintenance and repairs were conducted on both the launchers and their payloads throughout the conflict. To accomplish this, workshops were set up at various hide sites along the route taken by the launchers when transiting between fronts, where maintenance crews would inspect the vehicles and their missiles when they pulled in to take cover from hostile aircraft and reconnaissance assets.

All of this required careful coordination, as the maintenance teams needed to be in place prior to the launchers beginning their movements. Complicating matters further was that no maintenance/hide site could be used more than once, out of concern that the movements might have been detected by coalition intelligence platforms and the location designated for attack. This meant that the maintenance crews had to be continuously searching for hide sites that were both effective in terms of concealment and convenient in terms of access for the launchers.

The shift south after the second night of attacks on Israel created a pause in operations that General Ayoubi sought to minimize by sending the 4th and the 10th batteries back out west following their missile attack on Riyadh on the night of January 20.

The four Al Nida launchers of Unit 223 were established in the south, and as such able to maintain a modicum of pressure on the coalition’s forces operating out of Saudi Arabia. General Ayoubi then turned his attention to conducting a massed missile attack against Israel on January 25. To do this, however, he needed to move all of Unit 224’s MAZ-543 launchers back to western Iraq. He had two launchers—the 4th and the 10th—already operating in the area. Two others—the 2nd and 7th—were still undergoing repairs in Baghdad. This meant that Unit 224 would need to displace the six remaining launchers from where they were operating in the south of Iraq back north, through Baghdad, and from there to Ramadi and points west.

In addition to the MAZ-543 launcher, each battery had its own compliment of support vehicles which accompanied the launcher, including decontamination, reconnaissance, survey, and fuel and supply trucks. These would accompany the MAZ 543 in a loose convoy, with the result being that General Ayoubi’s order to displace Unit 224 put not six, but rather closer to forty, vehicles on the road. This was in addition to the scores of vehicles operated by the Technical Battalion and First Maintenance Unit, which were also on the move, setting up maintenance and refurbishment sites along the route.

Any time one puts more than 100 vehicles in motion at approximately the same time, headed in the same direction, there is the risk of this activity being detected by enemy reconnaissance, which would invite destruction from anyone of the hundreds of aircraft that were scouring Iraq, looking for precisely that opportunity. The key to survival for Unit 224 was to find a way to stagger the movement of these vehicles, and blend them into the natural pattern of activity, to make detection and interdiction as difficult as possible.

The launchers and their support vehicles represented half of the equation involved in launching a missile—the other half was the missile itself. During the Iran-Iraq War, and in the period between the end of that conflict and the Kuwait crisis, the Al Hussein missiles (and, prior to modification, the basic SCUD missile) were stored in warehouses at the Unit 224 base in Taji. The missiles were stored empty in the same so-called triple carriers they had been shipped in from the Soviet Union, so named because they held three missiles (two at the base, one on top). The guidance and control devices (gyroscopes and accelerometers) and warheads with fuses were shipped separately in their own special cannisters, as was the fuel “norm” for each missile, delivered in special made storage containers designed to be connected to fueling vehicles, which would pump the fuel from the container into the missile.

Under Soviet doctrine, a SCUD missile would be prepared for launch (fueled and armed, with gyroscopes programed and mounted) at the launch site. This would entail the launcher, together with a truck-mounted crane towing a missile mounted on a trailer, arriving at the designated launch site, joined by a fuel pump vehicle and additional vehicles carrying the fuel containers, and another vehicle carrying the warhead and fuse. At this point members of the missile technical battery would program the guidance and control devices for the missile. The gyroscopes of the missile guidance section were made ready for operational use by the missile technical battery through use of a special piece of calibration equipment mounted on the back of a ZIL-131 truck.

This equipment was critical to the success of the Al-Hussein launch, as the missile would not perform properly if the gyroscopes were not calibrated prior to the launch, thus permitting the missile to track where it was during its ballistic trajectory. There would also be a decontamination vehicle in case the nitric acid-based oxidizer leaked, and a water tanker. Preparation for launching a missile could take upwards of forty minutes to an hour, during which time the launcher and its crew were vulnerable to attack.

General Ayoubi had changed all of this. He dispersed the empty Al Hussein missiles, still mounted in their triple carriers, to various locations around Baghdad, as well as interim hide sites between Baghdad and the Ramadi missile support site operated by Unit 224, and a similar site near Amarah, in the south, operated by Unit 223. Likewise, the fuel and oxidizer containers were hidden among groves of date palms to prevent their detection, to be collected as needed.

At Ramadi and Amarah, the First Maintenance Unit divided the available fueling, warhead mounting and guidance support vehicles. Whenever General Ayoubi ordered an attack to take place, he would instruct the First Maintenance Unit to prepare the number of missiles necessary for the attack, along with additional missiles if there was expected to be an immediate follow-on attack the next day. While the launchers of Unit 224 and Unit 223 were making their way either to Ramadi or Amarah, the missiles they would use were being prepared—filled with fuel and oxidizer, warheads mounted, and guidance components programed and installed.

Each launcher was assigned a missile configured to be launched from a specific location toward a designated target. In this way, when a launcher arrived at either the Ramadi or Amarah support sites, they simply pulled up alongside their assigned missile, which was already loaded onto a missile trailer, and waited while the missile was lifted from its trailer and mounted on the launcher. This was the secret of how the Iraqis were able to reduce the time spent at a launch site to less than five minutes, and why the coalition was having so much difficulty interdicting them.

As efficient as this arrangement was in terms of reducing the exposure of the Al Hussein Force to attack at the launch site, however, it also translated into inefficiencies in operation. On several occasions, missiles would fail to launch due to fuel leaks brought on by the strain placed on the missile airframe incurred while being driven from the missile support site to the launch site. To help alleviate this problem, General Ayoubi instructed the Technical Battalion to periodically raise each launch arm to 45 degrees during their stops at the hide site/maintenance sites in route to the launch site, inspecting the missiles for leaks which, if detected, would be repaired by a crew from the First Maintenance Unit.

This was a delicate ballet which had to be carefully managed by the staff officers of the Al Hussein Missile force, ensuring not only that sufficient missiles, fuel and other support resources were available to both Ramadi and Amarah to meet the launch schedule, but also that the various component elements were themselves continuously moved from hide site to hide site to avoid detection. On top of this, the First Maintenance Unit and Unit 224, working in cooperation with the Project 144 engineers and technicians, continued to work at the bombed-out Taji missile support facility to repair missiles that had been taken out of service, as well as complete the assembly of new missiles, which would be inspected and certified for operational use.

And, always in the background, was the special weapons unit, which maintained ten fully configured and fueled missiles tipped with warheads containing botulinum toxin, as well as a dozen warheads filled with Sarin nerve agent that could be mounted on a regular Al Hussein Missile if needed. These weapons were stored in various locations northwest of Baghdad, near Nibae, and would be used against predesignated targets inside Israel only on the specific orders of Saddam Hussein or, in the alternative, if all communication was lost between the Al Hussein Force and the Iraqi High Command, in which case General Ayoubi was to assume the worst and execute the attack using the special warheads.

As careful as the Al Hussein Force was in implementing the vehicle movement plan and accompanying concealment activities, the underlying reality was that Iraq was a nation at war, fighting against an opponent possessing the world’s most advanced combat capabilities. Moreover, at any given time a significant percentage of these capabilities were singularly focused on destroying the Al Hussein Force; the Technical Battalion and First Maintenance Unit were repeatedly forced to move their operations within the Taji facility as the buildings they were using were systematically bombed.

The individual batteries likewise felt the pain of war. On January 22, while operating in the vicinity of Al Qurna, in the south, a group of vehicles belonging to the 3rd battery was struck by a bomb, causing one vehicle to overturn and catch fire. On January 24, the 8th battery suffered a similar fate while operating near Wadi Amij when an aerial bomb destroyed a water tanker, wounding three soldiers. And on January 25, a chemical reconnaissance vehicle belonging to Unit 224 struck a new type of weapon—an air delivered BLU-91/B “Gator” mine designed to impede traffic—which destroyed the vehicle and wounded four soldiers.

Despite the risks and difficulties, after implementing the mass displacement of six launchers, together with accompanying support vehicles, from the southern front to western Iraq, preparing a dozen Al Hussein missiles for operation, and avoiding destruction at the hands of the coalition air forces, Unit 224 was, on the evening of January 25, prepared to carry out the mass attack on Israel envisioned by General Ayuobi.

A New Plan

The consecutive mass launches of Al-Hussein missiles against Israel placed the delicate balance of relations between Washington and Tel Aviv at risk, threatening to snap the slender thread of restraint which held at bay the vengeance of the Israeli Defense Force. The recent arrival in Israel of Patriot ABM batteries manned by US soldiers had done much to alleviate the passions within the IDF which favored immediate retaliation on the part of Israel. However, the continued attacks by Iraqi Al Hussein missiles on Israeli targets forced the CENTCOM staff to reassess its SCUD threat elimination plan, the inadequacy of the current effort finally being acknowledged by even the most stubborn adherents of the old “48-hour termination” plan.

Israel, disappointed by US intelligence sharing efforts, demanded that it be permitted to fly an Israeli RF-15 phot-reconnaissance aircraft over western Iraq to support coalition targeting efforts as well as assuage Israeli concerns over battle damage assessment and target acquisition. Once again, the Israeli request was denied by the Secretary of Defense, Dick Cheney.

While Israeli officials raged in internal debate as to Israel’s eventual course of action vis-a-vis Iraq, CENTCOM frantically searched for a new strategy to cope with the suddenly resurgent Iraqi threat. In a coordinated effort between the CENTCOM Combat Assessment Cell and Current Intelligence Center, the CENTCOM Joint Operations Center, along with the Air Force component Intelligence Staff, a joint plan of action to eliminate the Iraqi SCUD threat was drafted and quickly brought to General Schwarzkopf’s attention for immediate implementation.

The plan sought to fulfill the campaign objectives regarding the Iraqi SCUD force as set down in the Desert Storm operations plan, which were to destroy Iraq’s fixed ballistic missile launch capability and SCUD-related maintenance and repair facilities as the primary objective, and to deny locations to which SCUD launchers may deploy as the secondary. The plan acknowledged that the limited knowledge of the Iraqi SCUD force and its operations had forced the coalition into a reactive vice proactive effort to eliminate the SCUD threat. The reason for this shortcoming was the unpredictability posed by the Iraqi mobile launchers and the lack of understanding on the part of the coalition concerning their employment.

The new joint SCUD elimination plan was broken into two distinct phases: Phase One sought to identify and fill the information gaps that were now evident in the CENTCOM comprehension of Iraqi SCUD operations, while Phase Two would destroy, disrupt, and/or deny Iraq the capability to continue SCUD operations through the exploitation of Iraqi vulnerabilities identified through the filling of information gaps.

Phase One proposed to use of special forces to reconnoiter possible Iraqi SCUD areas of operations to determine mobile SCUD unit locations and operational procedures. Operations during this phase were to be limited to reconnaissance and reporting only, reserving the use of force for follow on operations (the rationale for this course of action being that initial reconnaissance findings would likely lead to the discovery of even more important targets.)

Phase Two operations were themselves broken down into distinct operational periods. First, every SCUD launch site identified in Phase One would be attacked to both destroy fixed and mobile launchers and to deny these sites for future use. Attacks were to be conducted randomly throughout the hours of darkness, and against randomly selected targets, to disrupt and diminish Iraqi operational effectiveness.

Next, coalition aircraft would attack and destroy known and suspected SCUD support facilities, concentrating upon hardened aircraft bunkers located at airfields in known or suspected SCUD areas of operations. Other suspected support facilities and hide locations would be attacked as they were discovered.

Rapid reaction forces, comprised of dedicated attack aircraft and special forces teams, would be placed on alert to respond within 10 minutes to any targets generated by the special reconnaissance activities by other special forces, or tasking received by either national or theater level intelligence of possible SCUD activity.

The combined attack aircraft/special forces capability would then be used to conduct search and destroy operations attacking known targets, as well as scouring the area around Highway 10, other local highways, and the region around H-2 airfield. Other special forces teams would continue to locate additional targets, which would then be attacked using large-scale special operations, Ranger, and/or airborne forces.

This plan was designed to reduce and eventually eliminate the Iraqi SCUD threat against Israel and Saudi Arabia. While it would have undoubtedly had a greater impact on Iraqi SCUD operations had it been conceived prior to the start of Operation Desert Storm and implemented immediately upon day one of hostilities, even at this late stage in the war such a plan, aggressively implemented, would have made an impact.

The new SCUD elimination plan, however, was a victim of its own ambition. By signing off on the plan, General Schwarzkopf would be admitting the failure of Brigadier General Buster Glosson’s Black Hole, and ultimately the failure of Lieutenant General Chuck Horner’s strategic air campaign, to counter the single greatest threat facing the coalition at that time—Iraq’s SCUD missile force. Schwarzkopf could not see fit to commit to such a declaration. Instead of rejecting it outright, however, he killed it by doing nothing. The SCUD elimination plan, so carefully crafted by his own staff, was placed in limbo.

This is the last chapter of The Scud Hunters which will be published for all subscribers. From here on in, the book will be available to paid Substack subscribers only.

[1] George N. Lewis, Steve Fetter, and Lisbeth Gronlund, “Casualties and Damage from SCUD attacks in the 1991 Gulf War”, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, March 1993, p.47.

[2] Guy Gugliotta, “Battle-New Patriot Missile Soars to Stardom”, The Washington Post, January 19, 1991.

[3] Jeff Crawley, “Fort Sill Remembers First Patriot Missile Intercept”, Fort Sill Tribune, January 22, 2016.

[4] “Scud Buster”, Missile Defense Advisory Alliance, February 26, 2021; Cody M. Davis, Interview with Colonel (retired) Joe DeAntona, Missile Defense Advisory Alliance, March 3, 2021. The events of January 18 were not unique to Alpha and Bravo batteries; all in all, some 24 Patriot PAC-2 missiles were fired at 60 false targets generated from the considerable electromagnetic energy generated from other coalition forces, which penetrated the Patriot radar from its back, causing the Patriot radar software to process them as actual radar “hits”, or detection events. These accidental launches occurred during the first week of the conflict. The problem was resolved by January 23 by installing makeshift shrouds on the back of the Patriot radar, software modifications which filtered out false signals, and the reversion to manual mode, putting the operator back into the loop when it came to authorizing the actual launch of an interceptor missile. See Joeseph Lovece, “Electronic noise from US gear prompted errant Patriots”, Defense Week, September 28, 1992, p. 13, and Alexander Simon, “The Patriot missile: Performance in the Gulf War reviewed”, Center for Defense Information, July 15, 1996.

[5] General Khaled Bin Sultan, Desert Warrior, p. 252.

[6] General Khaled Bin Sultan, Desert Warrior, p. 352.

[7] This mission was not unique during Desert Storm—eventually some 260 distinct missions were flown which directly targeted Saddam Hussein. The intelligence-driven aspect of some of these missions was captured in William Smallwood’s book, Strike Eagle, where he describes a mission very similar in nature to mine—the targeting of a bunker near the city of Basra on January 23 (see Smallwood, pp. 154-157.) Smallwood also describes efforts to target specially modified Winnebago recreational vehicles which were being used by Saddam as mobile command posts (Smallwood, pp. 157-159.)

[8] Dan Balz and Rick Atkinson, “Powell Vows to Isolate Iraqi Army and ‘Kill It’”, The Washington Post, January 24, 1991.

Thank you, Scott, a great piece of history, wonderful that you kept good diaries! Everyone should subscribe to Scott's Substack to get these chapters! Here's how to save these: Start a new folder, "Scud Hunters" in your files. In your email program, find the "save as" button, click that, then under "file type" select HTML and save to your Scud Hunters folder.

Mr. Ritter is a cornucopia of information 🙏