Memories

Our history is fading away before us, in the failing memories of our elders. We must do a better job is listening and learning while they are still among us.

My Mom and Dad, who are 91 and 89 years of age, respectively, recently moved out of their home into an assisted living facility. This past holiday season I flew out to Palm Springs, California, to help my family sort of the myriad of issues associated with such a major life event. One of the things that needed to be done was sort through the various “stuff” that my parents had accumulated throughout their 66 years of marriage which could not make the trip to their new home. I was the designated “sorter”, identifying things that my sisters wanted to keep for their own, and trying to lay claim to the few things I wanted to keep as a reminder of my childhood, and my parents lives together.

I was taken aback when I discovered a box containing the various memorabilia that had attached itself to my fathers 26 years career as an officer in the United States Air Force. These plaques and certificates tracked the various units and organizations my father had served in over the course of his service to his country, and the awards he had received as a result of performing his military duties. My sister, who had no mind for these sorts of things, was prepared to throw them out in the trash. As a former Marine officer who understood the importance of these symbols of service, I could not accept such a fate for these items, imbued as they were with the history of my father and, because I had been a part of his life during this time, of myself.

I packed the box up and brought it home with me.

I was digging through the bottom drawers of my Mothers desk when I cam across a plaid cardboard box. Inside were various photographs depicting my parents childhood, their courtship and marriage, and their experience as parents to four children as they moved from one place to another to meet the needs of the Air Force. At the bottom of the box was a sealed envelope. The envelope was old, dating back to the mid-1960’s, and was from a photographic developing service. It looked like it had never been opened. I broke the seal, which yielded quickly, given the time that had passed, and poured the contents out onto a table.

These were photographs my father had taken during his service in Vietnam, a one year tour of duty that ran from March 1966 through March 1967. As I looked through the various images, I was struck by the presence of F-5 fighters, which were not part of the US Air Force inventory at the time. Then I remembered—my father had served with the 10th Fighter Commando Squadron—the famed “Skoshi Tigers.” It was an experimental unit, designed from the start to collect data on the combat performance of the F-5 so that it could be marketed to American allies (the US Air Force, it seemed, had no place for the F-5 fighter in its overall compliment of aircraft.)

I had questions—lots of questions. I had gone through my father’s things many times as a child, and at one point in time absconded with a flight jacket that bore the patch of the “Skoshi Tigers”. But my father very rarely talked about his service in Vietnam, other than the occasional stories about the Vietnamese themselves—like the time when he went out on a motorcycle tour around Bien Hoa air base, passed through a South Vietnamese checkpoint, and proceeded to drive through a series of villages where the occupants simply stared at the crazy white man smiling and waving as he drove through. On his way back he was pulled over by US military police, who had been summoned by the South Vietnamese. “You just drove through Viet Cong-controlled territory,” they told him. “You’re lucky to be alive.”

Indeed he was. Not everyone who served in the “Skoshi Tigers” was so fortunate. I remember in the 1990’s I had accompanied my parents to Washington, DC, where we were enjoying a nice walk in the National Mall. We found ourselves overlooking the Vietnam War Memorial. My father excused himself, and went over to an attendant, and asked a question we couldn’t hear. The attendant checked some documents, and replied to my father, who headed down to the black marble slabs engraved with the names of those who had fallen in that tragic conflict.

I looked at my Mother, who was very emotional. “He’s gone to say goodbye to John and Derald,” she said, barely containing herself. “They were his friends in the ‘Skoshi Tigers.’”

John Carlson was a pilot with the 10th Fighter Commando Squadron. On December 6, 1966, John, flying an F-5 Freedom Fighter under the callsign “Tiger 43”, took off from Bien Hoa Airbase as one of three aircraft flying a close air support mission against a VC support area near Lai Khe, some 25 miles north of Saigon. The three “Skoshi Tiger” F-5’s were flying close air support missions in support of the 1st Brigade, 1st Infantry Division, which was carrying out a coordinated attack on the Viet Cong in Binh Duong province known as Operation Bismark. The operation had begun on November 26, and was in its final phases (it eventually wrapped up on December 9) when Captain Carlson and his fellow “Skoshi Tigers” rolled in. Captain Carlson was relayed the location of enemy positions by an O-1 “Bird Dog” Forward Air Controller (FAC), who was in control of the airspace over the battlefield.

“Tiger 43” rolled in on his target, and delivered his ordnance, before being struck by small arms fire from enemy forces on the ground. Carlson’s aircraft immediately descended and crashed into the jungle near the target. The FAC did not observe either an ejection or parachute, and a search and rescue helicopter which entered the area after the crash and attempted to locate Captain Carlson found nothing.

John Carlson is one of 1,566 Americans whose remains have not been recovered from the Vietnam conflict. He was married, with two young daughters, at the time of his death.

His name is engraved on Panel 13, Line 8 of the Vietnam War Memorial.

An hour later, and some 20 miles to the west of Bien Hoa Air Base, Captain Derald D. Swift was flying close air support missions in support of the 196th Lightt Infantry Brigade near the village of Tay Ninh. The 196th Brigade, part of the 25th “Tropic Lightning” Division, was engaged in operations in support of Operation Attleboro, one of the largest ground combat operations of the Vietnam War. Captain Swift was delivering his ordnance when his aircraft was struck by enemy small arms fire. He nursed his aircraft toward Bien Hoa but was forced to eject about 10 miles short of the runway. His parachute malfunctioned and Captain Swift was killed.

My father was on strip alert to receive the damaged aircraft. He and the other members of the 10th Fighter Commando Squadron listened as their comrade broadcast his status, up to the point of ejection. They saw the black pall of smoke from the crashed aircraft. And they were their when Captain Swift’s body was recovered.

His name is located at Panel 13E, Line 19 of the Vietnam War Memorial.

I have vague memories of my father telling me story about his two friends. My father was an aircraft maintenance officer—he fixed airplanes instead of flying them. He didn’t get the recognition that the pilots got—they were the ones who dropped bombs on target. But the pilots knew who buttered their bread, which meant that when their aircraft was down for maintenance, they couldn’t fly. And the 10th Air Commando was staffed by pilots who wanted nothing more than to carry out their duties as US Air Force pilots.

Captain Carlson had teased my father that while he was the reason Carlson was able to fly his missions, it was Carlson who was going to receive the Air Medal, not my father. So Carlson cooked up a scheme where he got the O-1 “Bird Dog” FAC pilots to let my father fly as an observer on their missions. My father would be logged in as aircrew, and after 25 missions, he would qualify for the Air Medal. My father joked at one point that there was an M-16 in the cockpit. At one point in the flight, the pilot told my father to take the M-16 and start firing at a cluster of buildings.

“Why would I want to do that?” my father asked the pilot.

“Because they are shooting at us. I thought we’d return the favor.”

My father did as instructed, but stopped, unsure of what he was shooting at.

On future flights they moved the M-16 stayed up front with the pilot.

The plan almost worked. Between the O-1 flights, and hitchhiking on US Army helicopters running resupply missions to units in the field, my father had accumulated close to 20 hours of qualifying flight time—five shy of that needed for the award of the Air Medal.

But the deaths of Captain’s Carlson and Swift brought this escapade to an end. Anytime an aircraft goes down, there is an investigation into the maintenance records, just to make sure that some sort of mechanical failure did not contribute to the loss of the aircraft. In reviewing the records, the Squadron Commander, Lieutenant Colonel Robert F. "Earthquake" Titus, came across the flight records with my father’s name in them. It quickly became apparent to “Earthquake” what my father was trying to accomplish.

Soon my father found himself standing tall in front of the Squadron Commander’s desk, alongside the “Bird Dog” pilot who had been flying my father on his various observation missions. Both men were put on notice that if my father ever received the Air Medal, they both would be courts martialed for insubordination. My father’s job was to fix airplanes, not fly in them. That point was driven home loud and clear.

My father did end up getting a medal, but one for his role in keeping the F-5 fighters combat worthy during the intense period in November and December 1966, when the US Army was conducting massive ground operations targeting Viet Cong territory in and around Saigon. Many of the aircraft that were sent out came back with battle damage. My father was part of a team of maintainers whose job was to get these aircraft battle worthy. They did their job.

But there was a cost to pay, and the look on my father’s face as he was being decorated reflected the pain and suffering that accompanied this cost.

I never did talk to my father about John Carlson and Derard Swift. When he came back from paying his respects at the Wall, his eyes were moist, but he was composed. He didn’t say a word, but squeezed my mother’s hand as he walked past.

I just figured it wasn’t the right time.

After looking through the photographs, I met with my parent s for dinner at the dining hall of their new residence. I tried bringing up the “Skoshi Tiger's”, Bien Hoa, and that day at the Vietnam War Memorial.

My father suffers from advanced dementia, the main effects of which are short term memory loss. In short, we have the same conversation every five minutes or so. This has been going on for a few years now, but previously I’d be able to ask questions about the past, and my father’s memory was good enough to pull up some pretty detailed recollections.

When I asked about Vietnam this time, all I got was “I was stationed in a place called Bien Hoa.” I asked about what kind of aircraft he maintained, and his face went blank. “I can’t remember,” he said.

I should have had that conversation back at the Vietnam War Memorial.

My father never wanted to be an aircraft maintenance officer. His original passion was to follow in his father’s footsteps (my Grandfather, Irving Ritter, was an Army Air Corps pilot during World War I), and after graduating High School, my father enlisted in the Aviation Cadet Training program at Lackland Air Force Base, in Texas. My father underwent about ten weeks of training before moving on to the flight simulator, and then a final examination in the form of a one-hour “ride along” with an instructor pilot, who subjected the cadets to various high-G acrobatics. It was during this last part of the training that my father passed out in the aircraft due to the g-forces being exerted on his body. But the Air Force classified this as an “unexplained lack of consciousness”, and my father was removed from the program.

Behind every disappointment there is usually a silver lining to be found, and in the case of my father, it was the opportunity to meet my mother, who was serving as an Air Force nurse stationed at Lackland Air Force Base. My mother was actually dating my fathers roommate, another Aviation Cadet. But when she was involved in a terrible automobile accident which required her spine to be fused and made her medically unfit for service, my father’s roommate abandoned her. My father, feeling bad, continued to visit her in the hospital, sparking a relationship that blossomed into a marriage once both my father and mother were discharged from the Air Force.

My father attended the University of Florida on an Air Force commissioning program, where he trained to be a radio and television broadcast specialist. His dream was to be part of the Armed Forces Radio and Television Service. He got hands-on experience working at the University radio station and at Channel 5, WUFT, a Public Broadcasting stationed owned and operated by the University of Florida. He was a competent broadcaster, best known for playing the “Red Army Chorus” album in its entirety during the Cuban missile crisis in October 1962, prompting death threats from the local KKK and John Birch Society members.

My father graduated in May 1963, and received his commission. He fully expected the Air Force to send him to broadcasting school. Instead, they had him take an aptitude test, after which they said he was best qualified as an aircraft maintenance officer. When my father argued that he knew nothing about either aircraft or how to maintain them, the Air Force said they would train him.

And they did.

By 1964 my father was stationed in Homestead Air Force Base, assigned to the 308th Fighter Squadron. On February 8, 1965, my father deployed with the 308th to Cigli Air Base, outside of Izmir, Turkey, where the F-100’s stood a six-month stint on nuclear alert, where at least two aircraft were kept fueled, with a pilot in the cockpit and a nuclear bomb loaded onboard, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, for the entire deployment.

My father returned home in time for my fourth birthday. I remember him coming off the C-124 Globemaster aircraft, and into the arms of his loving family.

I remember him having to deploy with the rest of the squadron as Homestead Air Force Base was evacuated in September 1965 because of the approaching Hurricane Betsy, leaving his wife and three small children to ride out the storm in the shelter of base housing not known for its construction standards. I remember him coming home, and the family preparing for Christmas.

And then one day in March 1966, I woke up and my father was gone.

My Mom moved me and my two sisters to Sarasota Florida, where we lived in close proximity to my father’s parents and his sister, Shirley, and her family. This family support network would serve us well over the course of the next year, while my father was deployed to Vietnam.

My father’s experience base as an aircraft maintenance officer was, up until that time, exclusively with the F-100 “Super Sabre”. At the time of his arrival at Bien Hoa Air Base, situated north of the South Vietnamese capitol of Saigon, there was a significant presence of F-100 aircraft, and logic seemed to dictate that the Air Force would place a round peg in a round hole.

But fate dealt my father a different hand.

In 1962 the United States selected a new fighter aircraft, the F-5 “Freedom Fighter”, as the centerpiece of its Military Assistance Program, which oversaw the provision of combat aircraft to US allies in Europe and the Pacific. What separated the F-5 from the other fighter aircraft in the US inventory was that the United States Air Force did not fly the aircraft itself—it was purely intended for the export market. This cause problems, however, with potential clients, who believed that if the F-5 wasn’t good enough for the US Air Force, it wasn’t good enough for them.

To compensate for this lack of consumer confidence, the US Air Force, on July 22, 1965, formed the 4503rd Tactical Fighter Squadron (Provisional) (TFS[P]) at Williams Air Force Base, in Arizona. The squadron was equipped with 12 F-5As. These jets were modified with a non retractable air-refueling probe, external armor plating for the cockpit and engines, and updated avionics and ordnance delivery systems, resulting in a new designation: F-5C.

For the next three months, the 4503rd TFS(P) engaged in intense training program known by the nickname “Skoshi Tiger” that tested every aspect of squadron operations—including aircraft maintenance. Eighty eight days after the squadron was stood up, it deployed to Vietnam, arriving at Bien Hoa Air Base on October 26, 1965.

The F-5C’s flew their first combat missions that same day.

The “Skoshi Tiger’s” were at war.

For the next five months the men and aircraft of the “Skoshi Tiger’s” flew 2,664 sorties comprising a total of 3,116 combat flying hours. One aircraft was lost in combat and another 16 aircraft were damaged from enemy fire. Forty two sorties aborted due to technical problems.

On March 9, 1966, the mission of the 4503rd TFS(P) ended. But rather than return the squadron to the United States, as originally planned, the Air Force decided to extend the “Skoshi Tiger” project another year, with an eye to transferring the F-5C to the South Vietnamese Air Force.

In 1961 the Air Force had initiated a program, known as “Operation Jungle Jim”, to train foreign air forces, develop counter-insurgency tactics, and support emerging nations in Latin America, Africa, and Southeast Asia—including South Vietnam. In late 1961 the men of “Operation Jungle Jim” deployed to South Vietnam, where, operating under its new designation, the 1st Air Commando Group, it began a covert effort to build up what would become the South Vietnamese Air Force.

By the time the mission of the 4503rd TFS(P) came to a close, the Air Commando program was well established in South Vietnam, having helped transition the South Vietnamese Air Force into a number of aircraft types. With the new mission of transitioning the F-5C to South Vietnamese control came a new designation, with the 4503rd TFS(P) being redesignated as the 10th Fighter Commando Squadron (10th FCS).

The 10th FCS retained the nickname of the “Skoshi Tigers.”

The first commanding officer of the 10th FCS was Lieutenant Colonel “Earthquake” Titus. By the time he took command of the 10th FCS, “Earthquake” was already an Air Force legend, having enlisted in the Army as a paratrooper during World War Two, and then transitioning to the Air Force, where he flew 101 combat missions during the Korean conflict—including one where he was shot down over no man’s land and barely evaded being captured by the Chinese Communist forces. “Earthquake” had a distinguished record as a test pilot, and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for participating in the first flight of a single engine jet aircraft over the North Pole on August 7, 1959. “Earthquake” led from the front, flying numerous combat missions, including one which resulted him being awarded with a second Distinguished Flying Cross, with a combat “V” for valor, for flying close air support for an ambushed US Army convoy.

“Earthquake” went on to fly F-4 “Phantom” fighters over North Vietnam where, in the space of just a few days, he shot down three North Vietnamese MiG-21 aircraft, earning a Silver Star and Air Force Cross (the third and second highest awards for valor, respectively.)

I wanted to ask my father about “Earthquake” Titus—what kind of leader he was, and what characteristics stood out to my father. But when I brought up “Earthquake’s” name at the dinner table, my father’s eyes showed no hint of recognition. “I don’t remember anyone of that name,” he said.

My father’s photographs helped paint a narrative of his time in Vietnam. What I began to realize quickly is that he had been trained to maintain the F-100 “Super Sabre”, but now was being called upon to maintain a completely different aircraft—the F-5C—under combat conditions. My father hadn’t been with the 4503rd TFS(P) during its combat test and evaluation phase, and as such knew nothing of the lessons they had learned during their intense five-moth exposure to combat. The 10th FCS grew by a third—from 11 aircraft (there had been one combat loss) to 18 aircraft. This meant that the existing maintainers (those that remained) were spread thin. My father was literally thrown into the eye of the storm and forced to fend for himself.

This was another question I wanted to ask—what, if any, specialized training did he receive on the maintenance of the F-5C before being given the task of sending these planes—and their aircrew—off to war.

Again, my father’s failing memory was unable to produce an answer.

When my father returned from Vietnam, he brought back an inert (non-functional) 20mm cannon shell as a gift for his son. I loved this gift, and carried it with me everywhere I went—including the swamps on the outskirts of Edmonds, where we had rented a home. It was there, while playing “war”, I dropped my shell into the murky waters of an Edmonds swamp, never to be seen again.

I reported my loss to my father, who seem non-plussed about it. But when I pestered him to get me another, he finally snapped. “What I gave you meant something to me as well,” he said. “It was a part of my life. You lost it. We lost it. It is not coming back.”

This was a tough lesson for a six year old to learn, and one that wouldn’t sink in until later in life.

The F-5C was a lightweight aircraft that had developed a remarkable reputation for being able to deliver fire support with deadly accuracy. Because of their limited range, the F-5C’s of the “Skoshi Tigers” spent most of their time flying within 50-60 miles of Bien Hoa, providing close air support for US Army units operating in some very hotly contested areas. The 10th FCS aircraft would often be called upon to fly multiple sorties a day, back to back, to help out Army units that had become embroiled in heavy fighting. One of the main weapons available to the F-5C that came in very handy during these missions was its 20mm cannon. Loading the ammunition into the aircraft was a critically important task, because one mistake, and the gun would jam at a time when the soldiers on the ground needed it most. A jammed gun meant the Viet Cong enemy wasn’t being suppressed or neutralized, which usually translated into dead or wounded Americans.

My father and his crew took pride in the fact that their aircraft never suffered a malfunction when it came to the 20mm cannon.

The shell my father had given me had been presented to him by the Squadron Commander in recognition of this achievement.

That shell had a history.

Which is why my father took its loss so hard.

I wanted to ask him about this shell, and its meaning.

But his memory was no more.

Bien Hoa Air Base was in a war zone, something periodic Viet Cong mortar attacks made clear. On November 1, 1964, the Viet Cong had subjected Bien Hoa to a deadly 30-minute mortar barrage which killed four Americans and wounded dozens more. Several American and South Vietnamese aircraft were also destroyed. This attack prompted a re-examination of base security procedures and postures. By the time my father arrived, there were bunkers located throughout the air base where airmen and pilots were expected to take cover in case of attack. Because the 1964 attack had included a ground assault, each airman stationed at Bien Hoa was issued a personal weapon. My father recalled how when he arrived, he was taken to a firing range, where he was instructed on the use of a number of different pistols and rifles. But when it came time to shoot for score, my father’s aim was found wanting. After a conversation among themselves, the firearms instructors issued my father a .38 revolver, and told him to carry it with him into the bunker. “If the VC come through the door, just point the pistol at them and keep pulling the trigger,” the instructors told him. “If the bullets don’t kill them, the noise might just scare them away.”

The VC attacks on Bien Hoa were very sporadic during my father’s time there, usually consisting of one or two mortars fired with little attempt to aim or adjust. It got to the point where my father and the other officers would opt to remain in their bunks during the attacks, having developed a sense of immunity over time. That is until one day when a Chief Master Sergeant made his way past the officer’s quarters, toward the nearby bunker, after one particular mortar attack had begun.

“The bunker, gentlemen,” the Chief Master Sergeant growled. “We built it for a reason.”

My father and his two bunkmates reluctantly got up from where they had been laying down, and joined the grizzled senior enlisted man in the bunker, where they remained until the all clear signal was sounded.

Upon their return to their quarters, they discovered a hole in their roof, and a hole in one of their bunks. A mortar round had struck their quarters, but had failed to detonate. But the round had penetrated my father’s bunk—had he been lying their, it would have killed him for certain.

I remember the one time he told me this story, in the 1980’s when he was serving as a aircraft maintenance squadron commander at Hickam Air Force Base, in Hawaii. He was introducing me to the the senior enlisted member of his squadron, a Chief Master Sergeant. I had made a comment about how my father, by then a Major, was the ultimate authority in the squadron. “Well, son,” the Chief Master Sergeant said, a twinkle in his eyes, “your father will definitely generate more salutes than a person such as myself. But trust me— when someone with these on his shoulders”, he said, patting his uniform, “speaks, even the generals listen up. Each one of these stripes is a record of life lived, of experience learned and earned, in places remote and dangerous.”

That’s when my father told the story about the mortar.

“It’s a lesson I only had to learn once”, my father said. “When a Chief Master Sergeant speaks, act as if your life depends on it.”

“Because more often than not, it does.”

Both men laughed at my expense.

Later I found out it was this very Chief Master Sergeant who had, in an earlier assignment, saved my father’s life. They were doing a repair on an F-106 “Delta Dart” weapons bay, and my father was beneath the aircraft, peering inside the bay. The doors to the weapons bay were powered by a 1500 PSI hydraulic system which closed the door with enough power to cut a man in half. Apparently there is a distinctive sound made by the bay door before it closes. My father did not recognize this sound, but the Chief Master Sergeant did, and pulled my father back just as the bay doors slammed shut. If my father had remained where he was, and if the Chief Master Sergeant hadn’t intervened, my father would have lost his life that day.

These are the lessons of life one learns only by listening to their elders as they talk.

But in order for the elders to speak, they must remember. And at some point even the most invincible among us begins to fade with time.

It has been 60 years since the men of the 10th Fighter Commando Squadron—the famed “Skoshi Tigers”—assembled in Bien Hoa to begin their rendezvous with history. Between activization on March 9, 1966, and its de-activization on April 17, 1967, the 10th FCS flew 7,321 combat sorties, with 85 mission aborts. Seventeen aircraft suffered combat damage, while eight were shot down by enemy fire, resulting in three aircrew being lost.

Twelve F-5C’s from the 10th FCS inventory were turned over the the South Vietnamese Air Force in June 1967. The “Skoshi Tigers”, true to their “Jungle Jim” roots, had provided training to both pilots and maintenance crews in the final months of their year-long assignment. My father and the other personnel involved in this training had to take Vietnamese language lessons to assist in the communications between the instructors and the instructed.

My Mom had meticulously maintained a set of family photo albums throughout my childhood. I loved sitting down and going through these albums, bringing back memories of places visited and people met. These albums were maintained up until a few years ago, when my mother had the photographs digitized onto flash drives, which she disseminated to each of her four children.

The fate of many of the original photographs is not known to me.

Some of them were in the plaid cardboard box I had discovered in my mothers desk; these I kept.

But the envelope with my father’s Vietnam photographs was also in this box, apparently unopened from the time they had been developed.

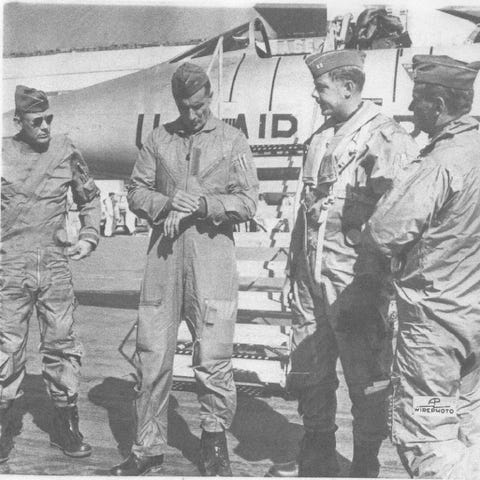

One photo from this group stuck out for me—a group photo with all of the pilots of the 10th Fighter Commando Squadron assembled in one location.

John Carlson is in this photograph. So, to, is Derald Swift.

I think back to my father’s visit to the Vietnam Memorial, and the emotions he had kept bottled up for nearly three years that were unleashed that day when he confronted their names on the wall.

Was this why the photographs had never been taken out of the envelope and displayed in the family photo albums? There were other pictures from the time of my father’s year-long deployment to Vietnam that were in the album. But thinking back, none of them were of the “Skoshi Tigers.”

I often look at this group photograph, and at the men assembled there. Young, strong, proud, in the prime of their lives.

Men with families, friends, wives, lovers, children.

Men who made a mark on this world, but whose deeds and accomplishments are trapped in wooden plaques destined for the trash bin, or photographs stuffed into a box stored in the lower drawer of a desk no body uses any more.

There is so much I want to know about these photographs, and the stories they tell.

Like why they remained in an envelope for nearly 60 years, never to be looked at by the man who took them.

When I got home from driving across country, my mind was racing with questions. I picked up the phone, and dialed my parents. My Mom answered the phone.

“I have a question about some of the photographs that were in the box you gave me,” I said.

My Mom hesitated. “I don’t know if I can help you,” she said. “Which photographs?”

I told her about the envelope that hadn’t been opened, and the photographs it contained of the “Skoshi Tigers” in Vietnam.

“Why were they photographs still in the envelope?” I asked.

“Why didn’t you put them in the photo albums?”

My Mom said she didn’t have a clue, and she called to my father.

It quickly became clear he didn’t have a clue either.

“I’m sorry, Scott,” my Mom said. “These are questions you should have asked 20 years ago, when both of our minds still worked. Now everything is fuzzy.”

Twenty years ago I had visited my parents in their home on the Big Island in Hawaii. My kids were around twelve years old. We went to the beach. We played golf. And we toured the island. In short, we had a grand time.

It never occurred to me to sit down and have a serious talk with my parents about their lives—our lives.

I just assumed that they would always be available for such a talk.

I am blessed that my parents are still alive.

Every day with them is a blessing.

But I have questions.

Many questions.

And the answers are wrapped up in memories that are no longer accessible.

Let this be a lesson to us all.

Go to your loved ones.

Talk to them.

Listen to them.

And remember everything they say.

Because one day, they won’t be there to say these things.

When they are gone, the only thing you’ll have left of them are the memories you gather.

Make sure you gather them before its too late.

Regards to your Father, Scott!

In the late seventies or early eighties of last century two strange aircraft appeared in one military airfield in Poland. They were F-4 Phantom and F-5 Freedom Fighter. Later I learned that they were being sent from Vietnam to Soviet Union for evaluation and to re-create manuals, which were destroyed by Americans (or South-Vietnamese) in 1975. But Soviet Union was not so interested in this business and sent them to Poland. Polish authorities were eager to do so, but for the squadron of those aircraft from Vietnam. This was, of course, impossible due to lack of compatibility with East-Block standards. So those two aircraft were standing in the airfield behind fence. Unfortunately, one drunk (probably) truck driver crashed with the Phantom damaging its wing and making aircraft not flight-worthy. And the remaining F-5 was sent (for unknown for me reason) to the factory WSK/PZL Okecie in Warsaw. It found its place in the hangar used to maintain and store planes owned by factory and Instytut Lotnictwa (something like NACA in USA). Everybody which have access to this hangar were warned that we don’t even see this F-5 as it was secret. I was working that time as a Design Engineer on military turboprop trainer PZL-130 Orlik and was responsible for designing the canopy. My boss wanted me to look how canopy of F-5 looks like. The problem was to go through the bureaucratic barriers to get uncertain permission. Decision was to make this intelligence gathering by stealthy way. One Sunday, when hangar was without people, and especially without boss of the hangar, me, and other Engineer (working on cockpit ergonomics) were forced to climb wire fence to look closely to things of our interest. What surprised me was the easiness how it was possible to lift by hand very heavy canopy using a build-in lever. In my opinion it was “over-engineered”. The mechanism with multiple links and with multiple springs took so much space, that it would be possible to put other person instead. But it was working perfectly. Other interesting thing I noticed was the beautifully designed system of removing and replacing both engines. They were attached to the lower part of the fuselage and it was possible to remove them using nice cart. All systems (fuel, control, sensors, power, hydraulic and fire prevention) were coupled to the airplane automatically. I think that the process of replacing engines in the field could last 20 minutes.

Why I am writing this story? Well, it is possible that I was touching exactly the same aircraft as your Father. Yes, world is very small…

You are the man of substance and honor, Major Scott Ritter. If we had presidents like you there would be peace, prosperity and harmony in the world. We need leaders of your great character and wisdom. Thank you for sharing your personal, and family stories.