An ABM Primer, Part Three: Throwing It All Away

The ABM treaty was the rock upon which all other arms control agreements between the US and the Soviet Union/Russia stood. And yet the United States opted to destroy this foundation.

(Note: This article contains material from my book, Scorpion King: America’s Suicidal Embrace of Nuclear Weapons from FDR to Trump, published in 2020 by Clarity Press. This is the third of a three-part series on the ABM Treaty, which served as the foundation for arms control in the nuclear era and without which there can be no meaningful progress in reviving arms control post New START.)

Ronald Reagan ran for office in 1980 on a platform that emphasized the need for arms control. For all his talk, however, Ronald Reagan and his administration had no viable arms control policy. Right-wing ideology had crafted positions so rigid and one-sided as to make them virtually worthless. Reagan’s pick to head ACDA, Eugene Rostow, had become increasingly frustrated over the constraints being imposed on negotiations by anti–arms controllers, such as Richard Perle in the Defense Department, and started demanding that he be given more flexibility in crafting a workable arms control policy.

This stance cost him his job, and in January 1983 President Reagan replaced Rostow with Kenneth Adelman, an archconservative neophyte on arms control. Rostow’s dismissal, and his replacement by Adelman, only reinforced the concern in Moscow that Reagan was utterly confused about how to approach the issue of restricting the arms race.

If the dismissal of Rostow sent tremors of concern through Moscow, what Reagan did next had to register as the policy equivalent of an earthquake. On March 8, 1983, in a speech delivered before the National Association of Evangelicals, Ronald Reagan lashed out at a Soviet leadership he called the “focus of evil in the world,” and labeled the entire Soviet Union an “evil empire.”

Clearly the Reagan administration was not positioning itself to build a sound relationship with the new Soviet leadership hade by former KGB Chief Yuri Andropov, who took over following the death of Leonid Brezhnev on November 10, 1982. Instead, building on the concept of mistrust, Reagan himself injected a new initiative that sought not only to undermine any residual goodwill that might exist between the United States and the Soviet Union, but also to shred one of the foundational documents of the modern arms control experience: the ABM treaty.

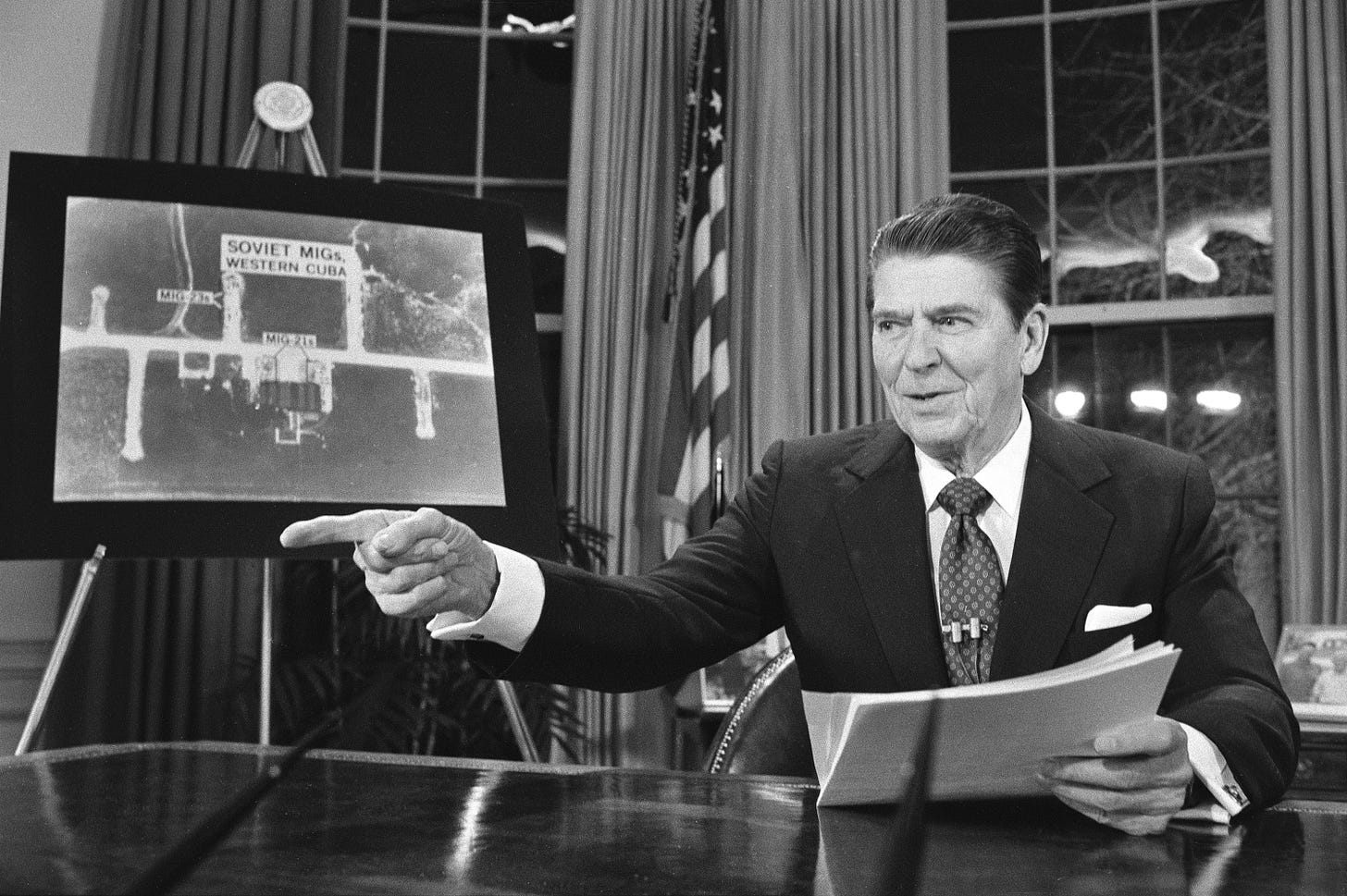

On March 23, 1983, President Reagan delivered a second speech, famously referred to as the “Star Wars” speech, in which he unveiled his administration’s intentions to deploy what was termed the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI). In a move directly challenging the foundation of conventional nuclear deterrence, Reagan announced the need for American defensive measures capable of rendering Soviet ballistic missiles obsolete. While Reagan claimed otherwise, the SDI initiative represented a direct attack on the ABM treaty and on the concept of equality when comparing U.S.-Soviet strategic power.

Although purely theoretical at this stage, this initiative meant that the White House, through the release of NSDD-85, “Eliminating the Threat from Ballistic Missiles,” was committing the United States down a path of long-range research and development for a ballistic missile defense program.

Reagan followed up his “Star Wars” speech with another primetime television appearance, this time to announce the findings of the Scowcroft Commission on ballistic missile options for the United States. Scowcroft, together with commission members such as Donald Rumsfeld, recommended that the United States deploy a hundred MX missiles, renamed Peacekeeper, to be deployed in existing Minuteman silos in Wyoming. This was seen as an interim measure until the United States could develop a more survivable basing mode for the Peacekeeper.

The combined effects of the “Evil Empire” and “Star Wars” speeches served to convince the Soviet leadership that the Reagan administration was serious about only one thing: the total domination of the United States over the entire world, including the Soviet Union. Andropov called the Reagan policies “madness” and warned that Reagan was walking an “extremely dangerous path.” The Soviets were growing increasingly concerned about the stalled talks on intermediate nuclear force (INF) and strategic arms reductions (START), and they feared that the Americans were using the talks as a vehicle to achieve a first-strike capability, concerns reinforced by Reagan’s pursuit of SDI.

The new secretary of state, George Schultz, spent the summer of 1983 trying to repair U.S-Soviet relations, and there was some minor progress actually made in terms of increased grain shipments and talks on the opening of new consulates. All of this was undone on the night of August 31–September 1, 1983, when the Soviet Air Force shot down Korean Air Lines flight 007, a Boeing 747 aircraft that had strayed deep into Soviet air space, killing all 269 persons onboard.

Immediately the Reagan administration reacted, not only condemning the act itself but also questioning the viability of dialogue with a nation capable of committing such an act. Information available today appears to defend the Soviet contention that they viewed KAL 007 as a U.S. reconnaissance aircraft, refuting the charges made by the Reagan administration that this was a deliberate act of murder. But Reagan himself kept upping the rhetoric, labeling the shoot-down as an act of “barbarism,” “savagery,” and “a crime against humanity.” When George Schultz met with Andrei Gromyko on September 8, 1983, in Madrid, Spain, what was supposed to be a time to celebrate a new direction for U.S.-Soviet relations quickly turned into a bitter exchange between the two senior diplomats.

In November the Soviet Union submitted one last proposal at the INF talks in Geneva, offering to reduce the number of intermediate-range missiles facing Europe to even lower numbers than they had agreed to under the moratorium. The U.S. delegation, still operating under the inflexibility of the Zero Option policy, rejected the Soviet offer, and shortly thereafter the United States began the deployment of its own intermediate-range missiles to Europe. The Soviets immediately withdrew from the INF talks.

In an effort to keep the START talks alive, Brent Scowcroft drafted a proposal calling for both the Soviet Union and the United States to reduce their nuclear arsenals according to the concept of equivalence, based on the disparities between the strategic forces of each side. This represented a departure from the previous Reagan demand of strict equality. Ed Rowney, the START negotiator, was opposed to the new proposal, and misrepresented it to the Soviets in Geneva, reinforcing to his Soviet counterparts that the “basic position of this administration has not changed.” The Soviets in turn refused to deal with Rowney and walked out of the START talks when they concluded in December 1983 without setting a date for their resumption.

U.S.-Soviet relations were frozen. Andropov, his health failing, condemned the U.S. actions in deploying INF to Europe, somewhat ominously warning about the “dangerous consequences of that course.” Later, in a December 1983 speech to Soviet war veterans, Soviet Defense Minister Ustinov accused the United States of breaking the military-strategic balance between the United States and the Soviet Union, something he said the Soviet Union was “determined not to allow.”

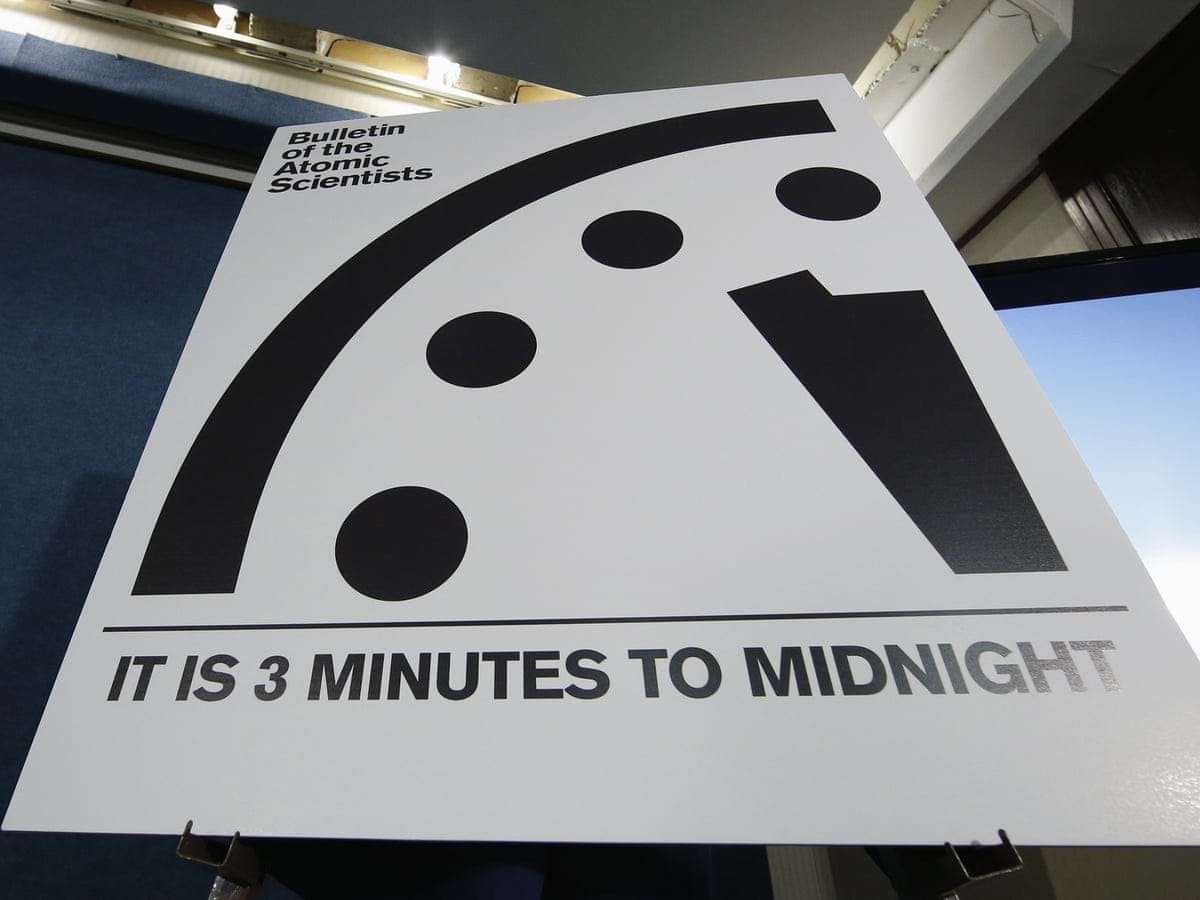

In January 1984, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists reset the Doomsday Clock to three minutes before midnight, citing the total collapse of arms control dialogue between the United States and the Soviet Union. The Cold War not only had grown colder but was in greater danger of becoming a “hot” war than any time since the Cuban missile crisis of 1962.

In Washington, DC, Soviet Ambassador Anatoliy Dobrynin joked that he should apply for unemployment benefits, given the fact that there was little or no work to be done in the way of U.S.-Soviet diplomacy. The collapse of the INF and START talks was symptomatic of an overall freeze in U.S.-Soviet relations. But there was no worse time than the end of 1983 for these two superpowers not to be talking to one another.

The decision by President Reagan to deploy INF to Europe in the fall of 1983 left the Soviet leadership concerned that the United States was pushing to acquire, and perhaps employ, a viable nuclear first-strike capability against the Soviet Union. In response, the Soviets began an intelligence collection effort designed to detect advanced warning of any U.S./NATO first-strike attack, and they put together an operational plan designed to pre-empt any such attack. The Soviet intelligence effort was geared toward collecting indicators of any impending attack. Thus, in early November 1983, when the United States held a full-scale rehearsal for nuclear war in Europe, code-named Able Archer 83, it appeared to the Soviets that the United States was moving forward with a first-strike attack against the Soviet Union.

Soviet nuclear forces were put on the highest alert and needed only a simple order from the ailing Yuri Andropov to launch a pre-emptive strike that would have triggered a nuclear holocaust. Exercise Able Archer 83 ended by mid-November 1983, and the crisis soon passed. Nevertheless, the deep underlying suspicion on both sides about one another’s intent still existed.

Much of the work for creating a strong anti-Soviet bias in the policies of the Reagan administration up until late 1983 was done by National Security Advisor William Clark, who had ready access to the president on a daily basis. Operating away from the spotlight, Clark carefully controlled the information the president had access to, helping color his judgments and, ultimately, his decisions. The incoherence of the Reagan arms control philosophy was, by the fall of 1983, being harshly criticized in the press. When the media, in August 1983, began suggesting that it was Clark, and not Reagan, who was calling the shots in the White House, it was simply a matter of time before Clark was asked to step down. The assault on Clark, orchestrated by White House Chief of Staff James Baker and supported by Nancy Reagan, resulted in his resignation on October 13, 1983. He was rewarded for his loyalty to the president by being appointed secretary of the Interior.

Clark’s replacement as national security advisor was Robert McFarlane, a former Marine Corps officer who had served in the White House on and off since the early 1970s. McFarlane did not share Clark’s “Evil Empire” approach toward the Soviet Union. While McFarlane had been one of the principal authors of Reagan’s 1983 “Star Wars” speech, his actions were motivated by a perceived need to break free of the previous patterns of behavior that propelled the United States and the Soviet Union on a collision course.

With McFarlane installed as national security advisor, an opportunity was created for a shift in of U.S.-Soviet relations in a more pragmatic direction. McFarlane was quick to act when U.S. intelligence reported, in January 1984, on the Soviet reaction to the Able Archer exercise. When Reagan found out how serious the situation had been in terms of a Soviet overreaction to the exercise, he was disturbed and soon thereafter made a speech, influenced by McFarlane, in which he declared that the top priority between the United States and the Soviet Union must be to reduce the potential for nuclear war and likewise reduce their respective nuclear arsenals.

On February 9, 1984, after only fifteen months in office, Soviet leader Yuri Andropov died. While Andropov had indicated that his successor should be Mikhail Gorbachev, the minister of agriculture, the Soviet Central Committee instead chose Konstantin Chernenko as general secretary. Chernenko was a protégé of Brezhnev, and his selection as general secretary represented a return to the hardline policies of that era. While assuring that the Soviet Union had “no need for military superiority,” Chernenko promised that he would seek a sufficient level of defense to “cool the hot heads of bellicose adventurists.” Soon after assuming the mantle of leadership, Chernenko sent a letter to President Reagan in which he embraced the “opportunity to put our relations on a more positive track.”

The National Security Council and State Department both began a move to renew serious dialogue with the Soviets. The continued deployment of INF missiles into Europe was a source of tension with the Soviets, who refused to engage in any renewed dialogue with the United States under these conditions. By the summer of 1984 Chernenko had rejected all American overtures on any resumption of arms control talks as election year tactics (1984 was a U.S. presidential election year) and demanded that the United States back up its words with concrete action.

None was forthcoming.

Instead, the Soviets were treated to a continuation of campaign-induced hardline rhetoric and gaffes, including one by President Reagan in August 1984, when an open microphone caught him joking about signing legislation that would “outlaw Russia forever” and concluding with “We begin bombing in five minutes.”

In the fall of 1984, the Soviet Union announced its first major defense budget increase in several years. Proclaiming that this move was a reaction to the massive defense spending undertaken by the Reagan administration, Soviet leaders, including Chernenko, Gromyko, and Ustinov, stressed the defensive character of their military buildup, although a major part of the funding increase went to testing and fielding a new generation of mobile ICBMs, including the SS-24, armed with ten MIRVs and capable of being launched from a standard silo or on special railcars, which gave it strategic mobility, and the SS-25 road-mobile ICBM, armed with a single nuclear warhead.

While some in the Soviet military pushed for even greater defense spending, Chernenko refused, unwilling to stress an already fragile civilian economic sector. In order to reinforce his decision to cap defense spending, Chernenko began a move toward improved diplomatic relations with the United States, starting in late September 1984 with a meeting between Andrei Gromyko and President Reagan. In October 1984 Secretary of State George Schultz met with Soviet Ambassador Dobrynin, and later Gromyko met with the U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union, Arthur Hartman. By November 1984 both sides were discussing the possibility of a Schultz-Gromyko meeting in early 1985 for the purpose of jump-starting nuclear and space arms talks.

But any breakthrough in U.S.-Soviet relations was hampered by uncertainties about Soviet leadership. While the elections of November 1984 cemented Reagan’s position as the leader of the United States for the next four years, the failing health of Konstantin Chernenko led to a behind-the-scenes power struggle that boiled down to two men: Mikhail Gorbachev and Grigory Romanov. Romanov was linked to the Soviet defense industry and represented old-style Soviet leadership reminiscent of the Brezhnev era. Gorbachev had already made his mark as a reformist with new ideas about the direction the Soviet Union needed to take. In a speech delivered in November 1984, Gorbachev had already raised two concepts—perestroika (rebuilding) and glasnost (openness)—that would later change the Soviet Union and the world. But Chernenko’s succession, as of the end of 1984, was very much in doubt, and this lack of certainty impeded any rapid improvement in U.S.-Soviet relations. Chernenko’s declining health worsened by the end of 1984, and the Soviet leader was confined to bed in a Moscow sanatorium for the final months of his life, finally passing away on March 10, 1985.

Gorbachev eventually beat out Romanov as the new Soviet leader in March 1985. He immediately repeated the trend of the previous two Soviet leaders in writing a letter to President Reagan reaffirming his “personal commitment…to serious negotiations.” The difference this time was that Gorbachev, unlike his predecessors, would follow up on his commitment.

Gorbachev was assisted by the diplomacy that had been conducted in the last months of Andropov’s rule. In the fall of 1984 both the United States and the Soviet Union had expressed an interest in entering into “umbrella” negotiations encompassing defense and space systems, START and INF. These talks began on March 12, 1985 in Geneva. With the advent of these talks, the Reagan administration installed a new team of negotiators. Gone was Ed Rowney, the hardliner whose antics had so alienated his Soviet counterparts. His replacement was Max Kampelman, a member of the CPD who had previously served as the U.S. ambassador to the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) from 1980 to 1983.

Little progress was made in these new talks, mainly as a result of the demand by the Soviet Union that the ABM treaty be strictly adhered to and the efforts by the United States to seek as broad an interpretation of the ABM treaty as possible so as to permit ongoing work on SDI. Secretary of State Caspar Weinberger and his assistant deputy, Richard Perle, sought to undermine the ABM treaty while opposing any new talks designed to impede SDI. Their work ran counter to the efforts of Secretary of State Schultz and National Security Advisor McFarlane, both of whom were keen on getting serious arms control talks with the Soviets back on track.

In an effort to help reduce tensions with Europe and the United States, Mikhail Gorbachev initiated a unilateral moratorium on the deployment of INF into Europe, which was scheduled to last until December 1985, by which time there was hope that a U.S.-Soviet summit could occur that would produce a more thorough blueprint for disarmament action. Talk of an early summit in 1985 cooled in April 1985, when an American officer, Major Arthur Nicholson, was shot and killed by a Soviet soldier while carrying out his duties as part of the Military Liaison Mission in Potsdam, East Germany.

The stalemated talks in Geneva began to frustrate both Moscow and Washington. Hardliners such as Weinberger and Perle continued to oppose any effort at negotiations between the United States and the Soviet Union. Since 1984 President Reagan had been presented with intelligence analysis pushed by Perle that asserted that the Soviet Union had violated its political commitment to adhere to the provisions of the SALT II treaty. Reagan had, since 1982, committed the United States to a path of adherence with the SALT II treaty, even though he was personally opposed to the treaty.

In June 1985, confronted with evidence that Perle and others contended proved the Soviets to be noncompliant in their agreements, President Reagan announced that the United States would continue to abide by the SALT II treaty so long as the Soviet Union demonstrated comparable restraint and provided that the Soviets pursue in good faith the ongoing arms reduction talks in Geneva.

Reagan’s position incensed Gorbachev, who accused the president of acting in bad faith by framing a scenario that was inconsistent with the facts. “One cannot dispute the fact that the American side created an ambiguous situation whereby the SALT II Treaty, one of the pillars of our relationship in the security sphere, was turned into a semi-functioning document that the U.S., moreover, is now threatening to nullify step by step,” Gorbachev wrote in a letter to President Reagan on June 10, 1985. “Your approach is determined by the fact that the strategic programs being carried out by the United States are about to collide with the limitations established by the SALT II Treaty, and the choice is being made not in favor of the Treaty, but in favor of these programs.”

It became clear to both Reagan and Gorbachev that the atmosphere in Geneva was not conducive to sound negotiations, and on the joint recommendation of Secretary of State Schultz and the new Soviet foreign minister, Eduard Shevardnadze, it was agreed in October 1985 that a back channel of communications would be established to bypass the usual diplomatic processes. Once again, the Soviets turned to their ambassador in Washington, Anatoliy Dobrynin, to carry out this function. Through this back channel, and in subsequent dialogue between Schultz and Shevardnadze, Reagan and Gorbachev began to discuss a mutual understanding concerning the “inadmissibility of nuclear war.” Both sides started working toward organizing a summit between the two leaders before the end of 1985.

The need by both sides to break free of the impasse that existed in Geneva over the issue of arms reductions was critical to the success of any summit. During a meeting in New York City on September 27, 1985, Shevardnadze presented President Reagan and Secretary of State Schultz with a new Soviet proposal on strategic arms reductions which proposed a 50 percent reduction in strategic arms by both sides, as well as a “cap” of 6,000 nuclear warheads per side. Furthermore, no basing mode (ICBM, SLBM, bombers) could contain more than 60 percent of the warhead total.

On November 1 the United States responded with a counterproposal that continued to reflect the U.S. focus on missile throw weight as a unit of measuring strategic capability. The U.S. proposed a 50 percent reduction in the highest overall ballistic missile throw weight, in addition to limiting re-entry vehicles to 4,500 for each side, with a sub-limit of 3,000 re-entry vehicles on ICBMs and a further sub-limit of 1,500 re-entry vehicles on heavy ICBMs. The desire for an early summit provided an opportunity for both sides to bridge their differences and bring their positions closer together.

Secretary of State Schultz traveled to Moscow in early November 1985 to meet with Shevardnadze and Gorbachev in order to help pave the way for the summit scheduled for later that month. Back in Washington, Richard Burt, the head of the Political-Military Affairs Bureau, supported Schultz. Burt was pushing for a successful summit defined by a meaningful agreement in the field of arms control.

Opposing Burt was Richard Perle, who, together with Secretary of Defense Weinberger, was concerned that in their rush to have a good summit, Schultz and Burt were positioning the president to make too many compromises to the Soviets. Perle drafted a memorandum that warned the president not to give in on issues of principle, especially SDI, even if the Soviets appeared to be making concessions elsewhere. The Soviets, Perle claimed, had a history of violating every arms control agreement they had entered. According to Perle, Gorbachev, despite his new style of open leadership, was no different from any other previous Soviet leader in that regard. In the end, Perle warned, no matter what the United States commits to, Gorbachev and the Soviets will cheat.

On November 19, President Reagan and General Secretary Gorbachev finally met face to face in Geneva, the first such meeting between U.S. and Soviet leaders in six years. Gorbachev pushed early for “a substantive agreement…which would increase peoples’ hope and would not destroy their view of the future with respect to the question of war and peace.”

In the discussions that followed, Gorbachev lectured the U.S. delegation that twenty years ago America had four times as many nuclear weapons as the Soviet Union. What would the United States have done if the situation had been reversed? Gorbachev asked. His answer: The same thing the Soviets did—seek parity. Today, Gorbachev noted, parity exists. The Soviets do not seek any advantage but rather would like to see strategic nuclear parity at a lower level than today.

The main problem was SDI, which Gorbachev contended could only lead to a renewed arms race inclusive of space weapons. SDI made no sense to the Soviets, who considered that its only utility lay in its potential to defend against a retaliatory strike, and as such facilitate a first strike option. This, Gorbachev stated, was unacceptable. If the United States went forward with SDI, then there could be no reduction in strategic nuclear weapons, and the Soviets would be compelled to pursue a similar program of its own.

President Reagan responded by declaring that SDI was not a threat, since it was not linked to any offensive military capability and therefore should not be viewed by the Soviets as a threat or trigger an arms race. Offensive weapons can and should be reduced, even with SDI. Gorbachev then asked Reagan what he thought they should tell their negotiators in Geneva, to which Reagan responded that guidelines seeking a 50 percent reduction in strategic arms would be acceptable, with some flexibility provided based upon the differing structure of U.S. and Soviet forces. But the sticking point continued to be SDI. Gorbachev pounded away on the issue, and it became clear that while the United States believed the principal destabilizing factor in U.S.-Soviet relations to be offensive nuclear weapons, the Soviets believed the same about SDI.

Schultz, in a side conversation with Shevardnadze, argued that the closer the two sides could get to zero nuclear weapons, the more viable SDI became in terms of eliminating the threat from offensive nuclear missiles. Shevardnadze responded by noting that if both sides were serious about eliminating nuclear weapons, and could get other nations to participate in their overall reduction, there would be no need for a defensive shield. These conversations were repeated, in one form or another, over the course of two days. In the end, the Geneva summit collapsed under the weight of Reagan’s SDI program and the refusal by Gorbachev and the Soviets to accept it as legitimate. The good news was that, after a six-year hiatus, the leaders of the Soviet Union and the United States had finally met and had come away from that meeting with a mutual recognition of the need for continued dialogue between the world’s two largest nuclear powers on the issue of the world’s most dangerous weapons.

While Gorbachev was dismayed with President Reagan’s close-minded embrace of SDI, his overall assessment of the American leader, and his policies, clashed with previous analysis from the Soviet Union, which held that the United States was seeking unilateral nuclear supremacy with the goal of being able to launch a pre-emptive nuclear first strike. Gorbachev believed Reagan had no intention of launching such an attack. His challenge was to convey this understanding to a Politburo that was disappointed with the lack of discernable results from the summit.

The major problem with SDI, from Gorbachev’s perspective, was political. Soviet scientists had studied the American concepts and concluded that SDI was fanciful, expensive, and unrealistic as an effective defense shield. The Soviets would be able to overcome any SDI shield with little or no problem, but at great expense, especially if Soviet defense interests insisted on building a similar shield in the name of “parity.”

Gorbachev had a good understanding of the poor economic state of the Soviet Union and realized that the reforms he wanted to embark on could not survive in the climate of a new arms race. At the Geneva summit Gorbachev had linked any movement in arms reductions with the United States dropping SDI. But now, post-Geneva, Gorbachev began to articulate disarmament policy options that accepted SDI as an unpleasant reality.

In January 1986 Gorbachev tried to jump-start arms control by proposing a three-phased deal that would scrap SDI, reduce each side’s strategic nuclear arsenal by 50 percent, and, in a move that took everyone by surprise, accepted the Zero Option when it came to INF. When the INF proposal bogged down in Geneva over the issue of linkage with SDI, Gorbachev made it clear, in a February 1986 meeting with Senator Edward Kennedy, that an INF agreement could be considered separate from strategic arms reductions and SDI.

In order to sell this position to his own side, Gorbachev moved to downplay the importance of SDI, telling the Politburo in March 1986, “Maybe we should just stop being afraid of the SDI.” Gorbachev stressed that the Soviets could not ignore SDI but needed to recognize that hardliners in the U.S. administration— namely Weinberger and Perle—were using SDI as a vehicle to push the Soviets into an arms race that would economically exhaust them. The secretary of defense and his hawkish assistant deputy were likewise now thrust into a position of opposing the very Zero Option on INF they had proposed back in 1981, because Gorbachev had done what neither of them thought any Soviet leader would ever do: accept the Zero Option disarmament proposal.

Gorbachev’s analysis was accurate. Back in Washington, both Weinberger and Perle, historically staunch opponents of arms control, were tentatively jumping on the arms control bandwagon. Their goal was not to create a viable arms control agreement, but rather just the opposite: to ensure that whatever arms control initiative went forward would be couched in a manner that was unacceptable to the Soviet Union.

Accordingly, Weinberger and Perle, assisted by Perle’s boss, Fred Ikle, and the new ACDA chief, Kenneth Adelman, launched a frontal assault on the two major pillars of U.S.-Soviet arms control, the ABM treaty and the SALT II treaty. For the ABM treaty, the Department of Defense hired a lawyer with no arms control experience to craft a legal reinterpretation of the ABM treaty that would allow for ongoing work in SDI. So expansive was this interpretation that even the State Department rejected it. The goal wasn’t to create a legal justification for SDI, but rather to push the Soviets into scrapping the ABM treaty altogether, something Gorbachev was loath to do.31

In a move that had surprised the hardliners in Washington, Gorbachev had broken from his previous insistence, articulated during the Geneva summit in November 1985, that any arms reduction effort must be linked to an American renouncement of SDI. Now, on May 29, 1986, Gorbachev submitted a new proposal that called for a two-phased approach toward disarmament. The first phase called for a cap of 8,000 nuclear devices for each side and a ceiling of 1,600 nuclear delivery vehicles each. Most telling, the Gorbachev proposal excluded the so-called Forward Based Systems comprising U.S. aircraft stationed in Europe and on aircraft carriers. The second phase would provide for “interim” reductions in strategic nuclear forces contingent upon both sides agreeing not to withdraw from the ABM treaty for a period of fifteen to twenty years.

These were serious proposals, but they were largely ignored in Washington, DC. Instead, the U.S. response was to return to a formula that differed little from what had been proposed in the past, including the insistence that the Soviet Union cut its throw-weight capability by 50 percent. Perle and Ikle also proposed a treaty to limit all ballistic missiles, noting that if there were no ballistic missiles, then there could be no U.S. nuclear first strike, meaning that the Soviets had nothing to fear from SDI. Countering the Soviet retort that if there were no ballistic missiles, there would be no need for SDI, the Reagan administration fell back on the “mad man” argument, noting that the United States, and the world, needed a defense against the potential actions of a rogue state and/or leader.

Gorbachev dispatched Shevardnadze to Washington, where he delivered a personal letter to President Reagan in which Gorbachev proposed a “quick one-on-one meeting, let us say in Iceland,” the goal of which would be to produce instructions to their respective negotiating teams in Geneva on “two or three very specific questions” that could then be signed as formal agreements when Gorbachev visited the United States.

Many in the Reagan administration, including Weinberger and Perle, were against the idea of a Reagan-Gorbachev get-together, feeling that meetings held at this level assumed a stature that mandated formal agreements, and that there might develop pressures to seek agreement for agreement’s sake. Schultz and others in the State Department rejected this, noting that in their opinion the Soviets were seeking to pave the way for a future summit in which arms control reductions might be discussed. Schultz was wrong, however.

In Moscow, Gorbachev sat down with the Politburo and emphasized the importance of the Soviet Union taking the lead in making dramatic proposals in the area of arms control. Final U.S. briefings provided to Reagan on the eve of his meeting with Gorbachev in Iceland predicted that the Soviet leader would be “coy” about the prospects of a future U.S. summit and that Reagan would have to press Gorbachev for action. The best the United States could hope for, the briefers told Reagan, was an agreement to limit the number of strategic nuclear warheads to something between the U.S. proposed cap of 5,500 and the Soviet position of 6,400.

The two leaders met in Reykjavik, Iceland on October 11, 1986, in a home formerly used by the French as a consulate. After an initial exchange of greetings and general remarks, during which Reagan chided Gorbachev for the Soviet Union not responding to the U.S. proposal calling for a 50 percent reduction in strategic nuclear arms (“perhaps the Soviets would agree to initial reductions to a level of 5,500 warheads,” Reagan prodded), the two leaders were joined by Schultz and Shevardnadze, and Gorbachev dropped his bombshell proposal: The Soviets were seeking nothing less than a 50 percent reduction in strategic nuclear arms, not tied to INF or any other negotiation, which would call for substantial reductions in Soviet heavy missiles. This proposal, Gorbachev noted, considered U.S. concerns. In exchange, Gorbachev asked for the United States to show some flexibility regarding American SLBM forces, which consisted of some 6,500 warheads.

On INF, the Soviets proposed a complete elimination of U.S. and Soviet INF missiles in Europe, separate from the issue of French and British nuclear forces. The Soviets proposed that the matter of Soviet INF missiles in Asia be put aside until all INF systems had been removed from Europe. The Soviets also proposed a freeze on the deployment of short-range nuclear missiles in Europe (possessing a range of less than 1,000 kilometers) and indicated a willingness to discuss the reduction of these missiles in future arms control discussions.

Gorbachev also brought up the issue of the ABM treaty, in which he proposed that both sides agree to a ten-year period during which they could not withdraw from the treaty and a period of negotiations (three to five years) in which they would discuss how to proceed from that point. Gorbachev also proposed a ban on anti-satellite weapons and a comprehensive nuclear test ban.

Reagan had little of substance to offer in response to the dramatic proposals outlined by Gorbachev. During a break in the meeting, evidence of a split in the U.S. delegation emerged, as Paul Nitze embraced the Soviet proposals as the most sweeping he had seen in over twenty years, while Richard Perle downplayed them as flawed and nothing new. Schultz was inclined to accept the Soviet proposal concerning the ABM treaty, citing the fact that since SDI was in its infancy, there could be no realistic discussion of fielding a system prior to that. As such, the United States lost nothing by agreeing. Reagan, however, refused to budge on the issue of SDI. This was to prove critical to the prospects of success in Reykjavik.

As the talks progressed, Schultz placed Nitze in charge of the expert-level discussions. Nitze’s counterpart was Marshall Akhromeyev, the senior Soviet military commander—his presence underscored the seriousness that the Soviets attached to these talks. Akhromeyev proposed a 50 percent reduction in strategic nuclear forces across the board, and in an effort to accede to U.S. sensitivities, he agreed that these cuts would be done in a manner that would not allow either side any discernable advantage. He also agreed that bombers would be counted as a single delivery system, whether or not they carried cruise missiles. The Soviets agreed to eliminate their INF missiles in Europe in exchange for the Americans agreeing to eliminate its INF missiles. The Soviets would keep their INF missiles in Asia, and the United States would be able to position a similar number of missiles in Alaska aimed at the Soviet Union.

The U.S. counterproposal, written with the heavy influence of Richard Perle, proposed a 50 percent cut in strategic nuclear weapons and a five-year agreement to limit SDI to research while abiding by the ABM treaty, which the United States continued to interpret in widely divergent ways. However, Perle was not able to hold back the tide for more sweeping arms control, which had gripped both delegations in Reykjavik. By the afternoon of October 12, President Reagan presented the Soviets with an offer to reduce each side’s strategic ballistic missile force by 50 percent in a five-year period, followed by complete elimination in a second five-year period. Both sides would agree to adhere to the ABM treaty during this time and not seek to withdraw.

The Soviets soon agreed to this formula, with one major exception: SDI research would, during this ten-year term, be limited to the laboratory, and there could be no testing of operational components outside of the laboratory or in outer space. Reagan would not accept this limitation, and Gorbachev refused to drop it. As a result, an opportunity for the Soviet Union and the United States to get rid of all strategic nuclear weapons was missed, defeated by a program, SDI, that was more theory than reality and that no one outside Ronald Reagan and a handful of advisors thought would ever be deployed. Reykjavik ended with both sides conceding that there had been no agreement reached on disarmament.

After Reykjavik, both the Soviet Union and the United States conducted post mortems designed to extract “lessons learned” from what appeared to be a failed summit. Back home in Washington, Reagan ran into a wall of criticism, as Congress and the Joint Chiefs of Staff confronted the reality that the nation’s chief executive almost negotiated away all strategic offensive nuclear weapons without first consulting them. Reagan found that he was soon compelled by domestic pressure to back away from some of the commitments made in Reykjavik.

The irony was that, at the same time Reagan began retreating from full nuclear disarmament, Gorbachev began to make concessions on the issue of SDI. Gorbachev seemed motivated by the words of Andrei Sakharov, the Soviet nuclear physicist who designed the first Soviet hydrogen bomb. Under house arrest in the city of Gorky since his dissent of the 1960s, Sakharov was released on the personal orders of Gorbachev. In his first public appearance, Sakharov chided Gorbachev for failing to embrace an opportunity to get rid of all nuclear weapons by seeking to restrict a concept, SDI, that would never work. Gorbachev listened to Sakharov and soon was crafting compromise language that would allow the United States to test SDI outside of the laboratory, but not in outer space.

In December 1987, President Reagan and First Secretary Gorbachev signed the INF treaty. At the end of May President Reagan took the ratified INF treaty with him to Moscow, where he and Mikhail Gorbachev met for their fourth summit. In addition to overseeing the depositing of the articles of ratification for the INF treaty, both leaders hoped that this summit could witness the signing of a new START treaty as well. They had agreed at the December 1987 summit in Washington that they should have a goal of finalizing a START treaty before Reagan left office. However, two new members of Reagan’s national security team, Defense Secretary Frank Carlucci and National Security Advisor Colin Powell, were not inclined to support a rush toward a START treaty. Although not as openly hostile to arms control as Weinberger and Poindexter, both Carlucci and Powell promoted a “go slower” approach that dismayed Secretary of State Schultz and led Reagan, in February 1988, to conclude that a START treaty would not happen during his time as president. Shevardnadze would continue to press Schultz on the issue of START, but a sticking point had developed over the issue of sea-launched cruise missiles, with the U.S. Navy opposing any effort to limit these systems’ nuclear role.

In the end, the Moscow summit was more ceremony than substance. Unable to come to an agreement on START, the two leaders engaged in a series of cultural activities, including attending the Bolshoi Theater. On May 31, 1988, Ronald Reagan spoke before the students and teachers of Moscow State University, where he addressed the issue of arms control between the United States and the Soviet Union, and in particular the stalled START talks. “We had hoped that maybe, like the INF Treaty, we would have been able to sign it [a START treaty] here at this summit meeting,” Reagan said. “We are both hopeful that it can be finished before I leave office which is in the coming January. But I assure you, that if it isn’t, I assure that I will impress upon my successor that we must carry on until it is signed. My dream has always been that once we’ve started down this road, we can look forward to a day, you can look forward to a day, when there will be no more nuclear weapons in the world at all.”

Reagan’s time in Moscow exposed him to the Russian people for the first time, and he was impressed by the experience. When someone asked him if he still believed that the Soviets were part of an “Evil Empire,” Reagan responded, “No, I was talking about another time, another era.”

In many ways the Moscow summit marked the end of the Reagan era. His second term was up in January 1989, and soon domestic American politics would require him to pass the torch of leadership to his successor in the Republican Party, Vice President George H. W. Bush. Bush, concerned about the conservative backlash that was growing in response to Reagan’s change of pace on all things Soviet, did his best to distance himself from Reagan’s rosy characterizations of the Moscow summit. The vice president did not attend the summit and, shortly after the summit ended, made headlines by declaring that “the Cold War is not over.”

In a speech to the United Nations General Assembly on December 7, 1988, the first by a Soviet leader since Nikita Khrushchev had pounded his shoe on the podium in 1960, Gorbachev announced that the Soviet Union would begin the unilateral reduction of conventional forces by cutting 500,000 men from the ranks of the Soviet military. These were real cuts, resulting in the elimination of six tank divisions stationed in Central Europe, totaling 50,000 men and 5,000 tanks. All in all, Gorbachev would reduce the Soviet forces in Europe by 10,000 tanks, 8,500 artillery pieces, and over 800 aircraft in phased withdrawals scheduled to take place over the course of the next two years.

To Gorbachev, this speech signaled an end to the Cold War and the beginning of a new era, when the Soviet Union would seek to interact with its neighbors and the world based on a foundation of ideas, not imposed by armed might. Gorbachev viewed his speech as groundbreaking, and it was. He was widely acclaimed as a visionary by the Western media and many Western politicians.

But the speech was designed to influence one audience, the new president-elect, George H. W. Bush. Here, Gorbachev would be disappointed. Prior to delivering his speech, Gorbachev had requested an opportunity to meet with President Reagan and President-elect Bush in what amounted to a fifth summit meeting. The three leaders met on Governor’s Island, in the harbor of New York City, following Gorbachev’s speech. While Reagan found the ideas put forward by Gorbachev appealing, Bush was less enthusiastic, telling a disappointed Gorbachev that while he “would like to build on what President Reagan had done,” he would “need a little time to review the issues” before he would be able to commit to any given course of action.

Gorbachev was pushing hard for an early summit meeting between himself and Bush in order to finalize a START agreement. But Bush and his new team of advisors, including Brent Scowcroft as his national security advisor, were not so keen on an early meeting. The new president, sworn in on January 20, 1989, wanted to create a gap between the “euphoria” of the Reagan administration and the “reality” of his own.

President Bush had assembled his national security team, led by Secretary of State James Baker, an experienced Washington insider who had recently served under President Reagan. It included National Security Advisor Scowcroft, another Washington insider with Reagan administration credentials; and Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney, a conservative Republican who had served as White House chief of staff under Gerald Ford before becoming a congressman representing the State of Wyoming (Cheney’s appointment actually came in April 1989, following the refusal by the Senate to confirm Bush’s first choice, Texas congressman John Tower, because of allegations of misconduct). Right from the start this team refused to buy into any notion of a “new era” of U.S.-Soviet relations and instead defined policy objectives in classic Cold War terms.

Brent Scowcroft did not see the need for any bold moves regarding U.S.-Soviet relations. In an appearance on ABC’s Meet the Press, the national security advisor declared that the recent developments involving the Soviet Union underscored the fact that “the West had won” the Cold War. As such, there was no need for any “dramatic change” in U.S. policy toward the Soviet Union.

Shortly after Scowcroft made that statement, the Soviet Union began its gradual slide toward oblivion. On April 9, 1989, Soviet troops violently suppressed a demonstration by over 10,000 Georgians in the streets of Tbilisi. Over 200 people were injured, and 19 were killed. While Gorbachev wrestled with this development, the Warsaw Pact began to display cracks in its foundation, as the Polish government recognized the labor movement Solidarity, led by Lech Walesa, and began collaborating with the Polish dissident to reform the Polish economy and political system. In this sea of turbulence all the United States could offer was a policy of “wait and see.”

In June 1989, President Bush announced a new set of proposals designed to help create the conditions under which a START agreement might be finalized between the United States and the Soviet Union. Known as the Verification and Stability Initiative, the proposal called for on-site inspection at missile production facilities involved in the manufacture of strategic missiles (similar to the kind of inspections already underway as part of the INF treaty), an exchange of data on the strategic missile forces of each side, the banning of all encryption of telemetry relating to missile tests, and other confidence-building measures that could be incorporated into a later treaty document.

However, the atmosphere in which arms control negotiations normally were conducted, amid Cold War–inspired superpower stability, no longer existed. Events in Poland and Hungary, two Warsaw Pact nations, were progressing to the point that President Bush was able to visit both nations in July 1989 and was greeted by hundreds of thousands of people anxious for change. In August 1989, the Lithuanian parliament declared the 1940 Soviet annexation of the Baltic States illegal, setting the stage for the declaration of independence of the Baltic States (Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia) from the Soviet Union. That same month, after a personal intervention from Gorbachev, the Polish government announced the formation of a coalition government that included Lech Walesa’s Solidarity movement.

In an effort to maintain the momentum needed for a successful arms control negotiation, Secretary of State Baker invited Soviet Foreign Minister Shevardnadze to his vacation home in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, for a summit. There Shevardnadze dropped the previous Soviet linkage between SDI and START, although he warned that the Soviets might withdraw from a START agreement if the United States did not abide by the ABM treaty (this was a warning about any attempt on the part of the United States to interpret the ABM treaty in any manner that permitted the deployment of SDI). The United States also dropped its insistence that all mobile missiles be banned under START, contingent on the Soviets agreeing to specific verification measures specifically for mobile missiles. Two of the major hurdles concerning a START agreement were thus overcome.

Arms control, however, soon took a back seat to geopolitics.

In early October 1989 Gorbachev visited East Berlin, where he announced that policy with regard to East Germany was made in Berlin, not Moscow. On November 9, following weeks of demonstrations and protests, the East German government announced that its citizens were free to visit West Germany and West Berlin. Soon East German citizens were scaling the Berlin Wall, greeted on the other side by crowds of enthusiastic West Berliners. Over the next weeks, the Berlin Wall was dismantled, and the process of German unification began. On November 28, taking matters into his hands, German Chancellor Helmut Kohl unveiled a plan for German reunification.

The issue of Germany’s future, and indeed the future of all of Europe, took center stage when, on December 2, 1989, Gorbachev and Bush met for their first summit meeting in Malta. While the two leaders discussed the importance of moving forward on a START treaty, arms control was pushed aside as the leaders of the world’s two largest nuclear arsenals instead discussed the end of the Cold War and the peaceful dismantling of the Warsaw Pact and, to a lesser extent, the Soviet Union.

Even as Bush and Gorbachev met, events continued to unfold in Europe at a rapid pace. On December 5, Czechoslovakia announced the formation of a non-communist government. The next day the East German leadership resigned. On December 20 the Lithuanian Communist Party declared its independence from Moscow, and on December 25, following a revolution in Romania, the Romanian leader, Nicolae Ceausescu, was executed in what was to be the only violent change of government to occur in Europe.

In August 1990, Saddam Hussein ordered the Iraqi invasion and occupation of Kuwait, triggering an international reaction culminating with the United States leading a “coalition of the willing”, empowered by a UN Security Council resolution authorizing the use of force. In January 1991 the United States and its coalition partners initiated Operation Desert Storm, a UN-sanctioned military action to liberate Kuwait. The fighting stopped in early March 1991, and by April the UN had passed a new resolution aimed at eliminating Iraqi WMD under the auspices of UN weapons inspectors. Both Desert Storm and the UN inspection effort could not have happened without the unprecedented level of cooperation that existed between the United States and Russia ta the time.

This good news was offset by an embarrassing development in London, where the G-7 economic summit turned down the Soviet Union’s application for membership. When President Bush traveled to Moscow on July 29, he was confronted with a growing schism between Russian President Boris Yeltsin and Gorbachev. Bush and Gorbachev were able to stage one last meeting in the grand style of past summits involving momentous arms control agreements, signing the START treaty in the spectacular setting of Saint Vladimir’s Hall in the Kremlin in a ceremony on July 31, which saw each leader using a pen crafted from metal taken from missiles destroyed as part of the INF treaty.

Less than three weeks later, on August 18, while Gorbachev was on vacation in the Crimea, a group of hardliners led by Vice President Gennadi Yanayev seized control of the Soviet government and announced the creation of a State Committee for the State of Emergency. Russian President Boris Yeltsin immediately denounced the coup. Soviet troops were called out but were met by hundreds of thousands of protesters. Brief clashes killed three demonstrators before the troops were pulled back. In a matter of days, the coup collapsed, and Gorbachev returned to Moscow. However, the situation in Moscow, and indeed throughout all of Russia and the Soviet Union, was forever changed. Yeltsin had emerged as the key player, and it was clear that Gorbachev’s days as head of state were numbered.

As the Soviet Union and United States entered the 1990’s, the issue of arms control continued to languish in the face of the tremendous change sweeping over Europe. By the end of October 1991, the Soviet Union was bankrupt, fiscally and politically. One by one, the republics that comprised the Soviet Union voted to secede. On December 1, Ukraine voted to leave the Union. On December 8, Boris Yeltsin met with the leaders of Ukraine and Belarus in Minsk and announced the creation of the Commonwealth of Independent States. Gorbachev resigned as the president of the Soviet Union on December 25, 1991.

The Soviet Union was finished.

Despite his victory over Iraq in Operation Desert Storm and his effective management of both the collapse of the Warsaw Pact and Soviet Union, President George H. W. Bush fell victim to the vagaries of domestic American politics, losing his bid for reelection to Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton. Under Clinton, the United States continued to fund missile defense research, which the Russians viewed as a potential violation of the 1972 ABM treaty.

Although the Clinton administration had announced the termination of Reagan’s SDI in July 1993, it only cut the space-based portion of the massive missile defense effort. Ground-based missile defense was still part of the U.S. strategic future. The ABM treaty was viewed by the Russians as a foundational agreement that was essential for all future arms control efforts. The Russians were extremely sensitive to the idea of the United States putting in place a missile defense shield the Russians could not hope to match in the foreseeable future, while at the same time they were reducing their arsenals of missiles.

Furthermore, Russia was getting rid of its larger systems, including the SS-18. The remaining ICBMs and SLBMs had a much-reduced payload capability, with the SS-25 operating as a single warhead system and the SS-N-20 carrying four warheads instead of eight. The United States, on the other hand, was retaining the Minuteman III and Trident D-5. While these missiles were downloaded from their Cold War capabilities, with the Minuteman III carrying one warhead instead of three, and the D-5 carrying eight warheads instead of fourteen, the Russians were concerned about a potential “breakout” scenario that had the United States deploying a limited SDI system and then uploading its Minuteman III and D-5 SLBMs to their maximum ability, achieving a first-strike capability backed up by a significant nuclear strike reserve and missile defense shield that would deter any Russian retaliation effort.

The Russian concerns were not mollified by the reality that it remained a tope goal of the United States under Bill Clinton to modify the ABM treaty to permit the fielding of a viable missile defense without killing the agreement were very much on the agenda.

The collapse of the Soviet Union created with it the need to modify existing arms control agreements to fit in with the reality that the United States now had a treaty relationship with not just one nation, but four. The need to bring Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan into the ABM treaty as successor states to the former Soviet Union was manifest. A 1996 Memorandum of Understanding on the issue of ABM succession was stalled, however, because of an ongoing struggle between Russia and the United States over the definition of the differences between a “theater missile defense” system and the “strategic missile defense” systems covered by the ABM treaty.

The defining characteristics of concern worked out between the United States and Russia in June 1996, involved the speed of the interceptor missiles. “Low-speed” interceptors, up to and including velocities of three kilometers per second, were to be defined as theater missile defense systems and permitted, while “high-speed” interceptors (anything above the threshold velocity) were deemed “strategic,” and subject to the ABM treaty restrictions. However, differences of opinion on how to precisely demarcate “high-speed” interceptors led to the collapse of the negotiations without reaching a final agreement in October 1996.

In January 1997 the Republicans in the Senate, led by Trent Lott of Mississippi, introduced the National Missile Defense Act of 1997, which mandated the creation of a theater missile defense system by the year 2003. This was more of a political maneuver than a sincere effort at legislation, for although the bill made it out of the U.S. Armed Services Committee in April 1997, it went no further.

However, the Senate action provided enough pressure to compel Clinton and Boris Yeltsin to meet, on March 21, 1997, in Helsinki, where both leaders agreed to the original demarcation agreement of June 1996. By September 1997 Russia and the United States had agreed to a framework that expanded the ABM treaty to include Belarus, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan, in addition to Russia, and to define parameters for both low-velocity and high-velocity missile interceptors as part of a permitted theater missile defense system. In April 1998, Boris Yeltsin submitted the ABM agreement to the Russian parliament for ratification, paving the way for a more solid framework of arms control agreements between the two nuclear-armed nations.

Arms control as a theme was no longer en vogue politically in Washington, DC. Instead, there was a rush to highlight the concept of “emerging threats” and the need to confront them. In early 1998 the Clinton administration empanelled (at the urging of the Republican controlled Congress) the Commission to Assess the Ballistic Missile Threat to the United States, more commonly referred to as the Rumsfeld Commission, after its chair, former secretary of defense (under President Ford) Donald Rumsfeld, who was nominated for the post by conservative Republicans in Congress.

Meeting from January through July 1998, the Rumsfeld Commission issued its report on July 15, declaring that the ballistic missile threat to the United States was so great that “the United States might have little or no warning before operational deployment.” The report highlighted the missile threats from “rogue regimes” in Iraq, Iran, and North Korea, noting that the United States would be vulnerable to a missile attack from these nations within a ten- to fifteen-year period.

Having created the Rumsfeld Commission, the Clinton administration could not ignore its findings. Not surprisingly, the Commission’s report was used by opponents of the ABM treaty to justify the need for a missile defense shield. Under pressure to be seen as responding to the threat postulated by the Rumsfeld Commission report, Clinton approached Russian President Yeltsin in January 1999 with a proposal that would allow for a modification of the ABM treaty to provide for a limited theater missile defense system that would protect the United States from potential rogue states.

In June 1999, following the end of military operations against Yugoslavia, President Clinton and Boris Yeltsin met in Cologne, Germany, where they agreed to put the Kosovo experience behind them and begin focusing on a new round of discussions concerning the ABM treaty. Both presidents knew that they were up against the end of their respective terms in office and that a breakthrough was needed if there were to be any hope of completing an agreement before the end of 2000.

Yeltsin agreed to honor President Clinton’s request for Russia to reconsider its opposition to any modification of the ABM treaty but was unable to translate this agreement into anything substantive. On July 23, 1999, President Clinton signed the Missile Defense Act of 1999, which put the United States on the track of deploying an active missile defense system. This action, conducted outside of any discussion with the Russians, caused the Russians to rescind Yeltsin’s commitment when U.S. and Russian negotiators met in Moscow in August 1999.

On December 31, 1999, Boris Yeltsin announced his resignation as president of Russia. Yeltsin appointed Prime Minister Vladimir Putin to take over as acting President until elections could be called in March 2000. Putin was a previously unknown former KGB official who had risen to post-Soviet political prominence in Saint Petersburg before becoming prime minister in early August 1999.

The surprise resignation of Boris Yeltsin put a freeze on U.S.- Russian relations, as both nations sought to take stock. Vladimir Putin was a relative unknown, and his interim status made meaningful negotiations problematic. Putin’s decisive victory in the Russian Presidential election on March 26, 2000, in the first round of balloting, cemented his status as Russia’s legitimate leader. He was inaugurated as president on May 7 and immediately began planning for an early summit meeting with President Clinton in order to get the U.S.-Russian relationship back on a positive track.

In early June the two presidents—one just starting his term, the other nearing the end of his—met in Moscow. While there were hopes that the two leaders would be able to reach an agreement on missile defense and a START-3 agreement that reduced the nuclear warheads on each side to between 2,000 and 2,500, in the end all that could be accomplished were two minor agreements on the control of Russian plutonium, and a joint U.S.-Russian military effort to monitor against accidental missile launches. Clinton was under pressure not to agree to any further cuts in the U.S. nuclear arsenal without first securing a missile defense agreement. The U.S. nuclear strategy was built to accommodate a 2,000 to 2,500 warhead figure. Any reduction beyond this level placed the United States at risk, according to the Pentagon, especially if it did not have a missile defense shield to fall back on. As for Putin, he pushed for even greater warhead cuts but was uncompromising on the issue of missile defense. While begrudgingly acknowledging that there could be a future threat from a “rogue nation,” Putin declared that missile defense was “a cure worse than the disease itself”, if for no other reason that it enabled a first strike capacity.

The summer of 2000 saw the U.S. presidential elections in full swing. While Clinton was in Moscow, Republican hardliners, including Senator Jesse Helms and the Republican Party candidate, Governor George W. Bush of Texas, warned Clinton not to undertake any obligations that would tie the hands of the next president. With the Moscow summit a failure, Clinton had little choice but to acknowledge that the issue of a U.S. missile defense system was one that would be handled by the next administration, headed by either Al Gore or Bush.

On September 6, 2000, Presidents Clinton and Putin met for the last time as national leaders, at a summit held in New York City. The two men signed the “Strategic Stability Cooperation Initiative,” a document that recommitted both nations to undertaking, and in some cases extending, existing bilateral arms control and nonproliferation agreements and initiatives. All existing bilateral arms control treaties were reaffirmed, including the ABM treaty.

All eyes were now on the upcoming elections in November 2000. Whoever won would have to deal with the mixed bag of arms control successes and miscues that marked the Clinton presidency. One thing was certain: The future of U.S.-Russian arms control and nonproliferation cooperation would hinge on the issue of missile defense. Given the insistence on the part of the U.S. to pursue limited missile defense, the prospects of sustaining the viability of the ABM treaty seemed slim. It would be up to the next president to define the path America would take about its arms control policy.

The 2000 presidential election was like none other in modern American history. Although the Democratic candidate, Vice President Al Gore, won the overall popular vote, the Electoral College vote, which constitutionally decides the election, came down to the State of Florida and some contested ballots from a handful of counties. In a legal showdown worthy of a Greek drama, the final decision on the disposition of the votes was made by the United States Supreme Court, which after a delay of over a month, ruled that Governor George W. Bush had won the Florida election, and with it the presidency.

The new Bush team entered office with a sense of certainty on what direction it wanted to take on a few critical issues, including the matter of arms control. As a candidate, George W. Bush had stated that, if elected president, he would “offer Russia the necessary amendments to the ABM Treaty so as to make our deployment of effective missile defenses consistent with the treaty.”

However, shortly after coming into office, the Bush administration began pushing for a series of new missile defense plans, including the construction of a missile defense “test bed” in Alaska (designed to counter a North Korean missile attack as postulated by the Rumsfeld Commission report) that would directly challenge the terms of the 1972 ABM treaty. As early as May 1, 2001, President Bush, in a speech delivered at the National Defense University, was talking not about remaining “consistent” with the ABM treaty but rather about moving “beyond” that treaty.

The missile defense system that the Bush administration was proposing to field was a far cry from the space-based, advanced technology-driven “Star Wars” system that had been proposed by President Reagan. Instead, the Pentagon was envisioning a more limited system, at least at the start, which combined ground-based interceptors with advanced surface-to-air missiles based on U.S. Navy ships to create a “shield” that could shoot down a small number of missiles launched from any potential rogue nation.

On the surface, the concept was attractive: an insurance policy against the irrational acts of nations operating outside the framework of international law and human decency. But in embracing this moralistic argument, the Bush administration ran up against the reality that a missile defense shield had long been viewed as a force of destabilization, a modern-day Maginot Line that would compel potential adversaries threatened by the notion of a nuclear-armed America hiding behind a missile defense system to find the means of overcoming that shield, thereby setting off an expensive arms race.

The fact that the technology the Bush administration was planning to deploy, even in its scaled-down version, was still untested only further underscored the arguments of those opposed. But the Bush team, headed by Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld, and backstopped behind the scenes by Deputy National Security Advisor Stephan Hadley (who had worked on ABM issues during the presidency of George H. W. Bush), firmly believed that some form of defense shield was better than no defense shield at all.

The ABM treaty was a flawed product of times long past, they noted, and Russia today was not the Soviet Union of the past, in terms of either intent or capability. New threats were emerging, manifested in the present by nations such as North Korea and Iran, with no guarantees that even greater threats would not emerge in the future. As such, the United States should no longer be constrained by Cold War thinking.

In his first meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin at the G-8 Summit in Genoa, Italy, held in July 2001, President Bush drove home this point of view, advocating reworking the ABM treaty in exchange for even greater strategic force reductions. The two leaders quickly expressed a sense of mutual admiration for one another, referring to each other as “friend.” But behind the warm rhetoric lay ideological differences that made it clear that the Bush ABM policy would not be warmly received in Moscow. The Russian president continued to call the ABM treaty the “cornerstone” of arms control.

Led by Condoleezza Rice, who argued that Russia no longer carried the influence it did when it was part of the Soviet Union, the Bush administration shrugged off the Russian protests as largely irrelevant, since in their view Russia was not in a position economically or militarily to challenge the United States. This mindset was clearly demonstrated during the visit of the Russian deputy chief of staff, General Yuri Baluevski, to the United States in August 2001, for the purpose of discussing possible amendments to the ABM treaty that would enable the United States to test a limited missile defense system. Baluevski continued to propose a solution that was linked to the conditions and restrictions set forth in the ABM treaty. His U.S. counterparts responded by stating bluntly that in order to accomplish what it wanted, the United States viewed the ABM treaty, if it was to continue to be referred to, as existing in name only.

On November 13–15, 2001, Russian President Putin visited President Bush in Washington and later at the Bush family ranch in Crawford, Texas. The two leaders discussed a wide range of issues, including the ongoing situation in Afghanistan, U.S.-Russian economic relations, and Russia’s relationship with NATO. But the main focus of the meetings was on the issue of missile defense, coupled with new strategic force reductions.

While Putin had come into the meetings still holding out that a compromise could be reached that permitted the United States to test its missile defense system within the framework of the 1972 ABM treaty, the Bush administration, led by National Security Advisor Rice, made it clear that it was, in the opinion of the United States, time to “move on,” beyond the ABM treaty. Noting that the ABM treaty no longer represented a foundational role in defining U.S.-Russian relations, Rice, together with Secretary of State Colin Powell, signaled that its demise was all but certain.

On December 13, 2001, President Bush announced that the United States would withdraw from the 1972 ABM treaty, triggering the six-month notification process called for by that agreement. “I have concluded the ABM treaty hinders our government’s ability to develop ways to protect our people from future terrorist or rogue state missile attacks,” the president said.1

Bush had hinted as much to Putin during their meetings in November, so the Russian president was not taken completely by surprise. Putin, in response, labeled the U.S. decision a “mistake” and urged the United States and Russia to move quickly to create a “new framework of our strategic relationship.” Putin also addressed the Russian people, assuring them that the U.S. decision “presents no threat to the security of the Russian Federation.”

On June 13, 2002, the United States formally withdrew from the ABM treaty, as promised by President Bush. The next day, June 14, Russia declared that it would no longer abide by START-2, meaning that Russia would seek to build new missiles and equip those and their current inventory with MIRVs as they saw fit.

The Bush administration was not concerned by the Russian moves—Secretary of State Colin Powell had previously indicated that such a move was of no concern to the Bush administration, which no longer viewed Russia as a threat and therefore would not interfere with whatever moves Russia deemed necessary to defend itself.

When President George W. Bush entered office, the United States held the fate of arms control in the palm of its hands.

Then he proceeded to throw it all away.

(I will be travelling to Russia in March to continue my efforts to promote arms control and better relations between the US and Russia. As an independent journalist, I am totally dependent upon the kind and generous donations of readers and supporters to underwrite the costs associated with such a journey (travel, accommodations, meals, studio rental, hiring interpreters, video production and editing, etc.) I am grateful for any support you can provide.)

Excellent intel. Thank-you braveheart Scott

So sad our so called leaders can’t give peace a chance in perpetuity.