Alas, Babylon

The "Polish Pope" Crisis of October 1978 made me a believer in the danger of nuclear weapons, and the need for arms control.

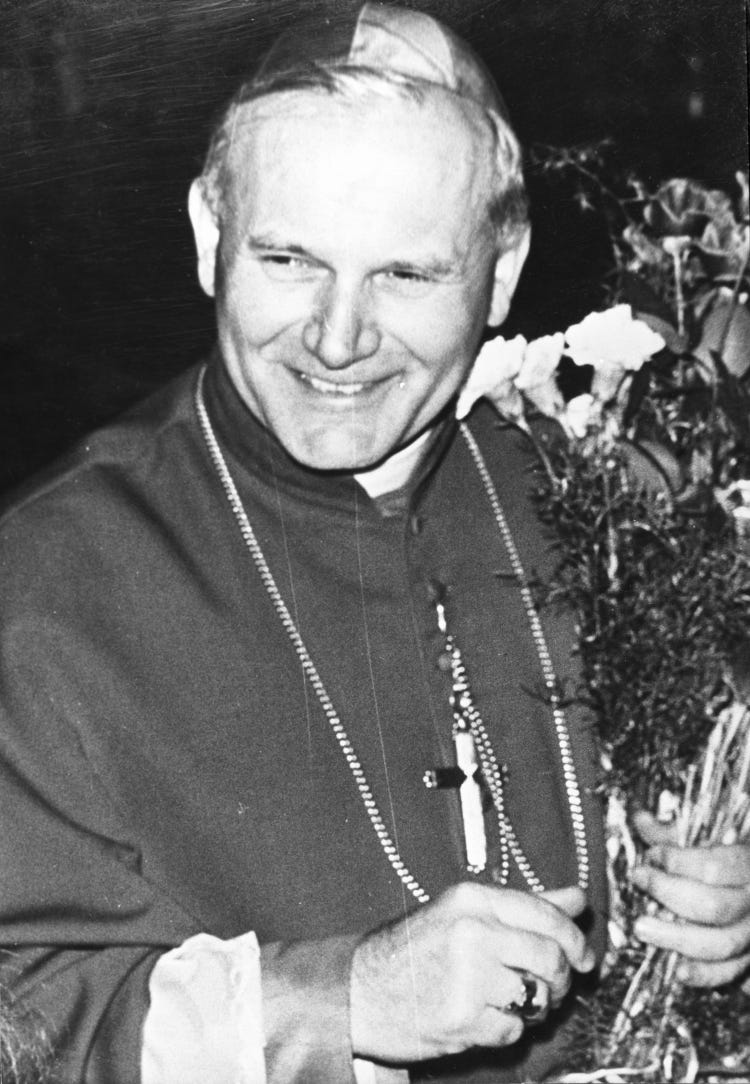

In the late afternoon of October 16 1978, 111 cardinals-electors from all over the world, who had gathered on 15 October 1978 in St. Peter Basilica, and after eight rounds of voting, elected 58-year-old Archbishop Karol Wojtyła to be Pope. John Paul II, as Karol Wojtyła became known, was Polish, and Poland at that time was part of the Soviet-dominated Warsaw Pact, where religion had for decades been subordinated to Communist Party dogma.

Throughout Poland, crowds poured into the streets in a massive display of spontaneous joy. In Krakow, the Sigismund bell that hung in the former royal castle in Wawel was rung—an occurrence only reserved for the post extraordinary circumstances. People paraded through the streets, national flags on display, singing religious songs and hymns that were officially prohibited from singing. A spark was lit in the hearts of the Polish people which gave birth to the Solidarity movement two years later.

Joseph Stalin is reported to have mocked the Catholic Church with his famous remark, “The Pope—how many divisions has the Pope?”

The answer to that question was being provided by the people of Poland themselves—millions flooded the streets in a massive display of unauthorized social mobilization that shook the ruling Polish Communist Party to its core. While the people of Poland danced in the streets, the state-controlled Polish TV and radio network remained silent while the ruling Communist Party consulted among itself as to what the next steps might be,

There were 40,000 Soviet troops stationed in Poland, serving as a mailed fist designed to reinforce the 300,000-strong Soviet Group of Forces in Germany that would lead off any war with NATO. Poland was viewed by Soviet authorities as an essential component of the Warsaw Pact, the foundation upon which its ability to successfully confront NATO on the field of battle was anchored.

Soviet officials, led by KGB Chief Yuri Andropov, were on the alert for signs that the new Polish Pope was part of a larger US-backed plot to create instability in Poland sufficient to require Soviet military intervention, weakening the unity of the Warsaw Pact and undermining the position of the Soviets in East Germany and elsewhere. The CIA viewed Poland as a particularly volatile member of the Warsaw Pact, noting in a 1977 analysis that a “blow-up” in Poland could bring down the Polish government “and even conceivably compel the Soviets to restore order” in a re-play of Czechoslovakia in the Spring of 1968.

The CIA viewed the Polish Catholic Church as a critical player in any scenario involving social unrest in Poland, noting that the Communist Party had been leaning on the Church to help stifle anti-government sentiment among the deeply religious Polish population. The election of Karol Wojtyła as Pope would collapse the role played by the Polish Catholic Church in underpinning the legitimacy of the Polish Communist Party.

The US had been preparing the grounds for such a move, putting pressure on the West German Catholic leaders to support Wojtyła. Zbigniew Brzezinski, the National Security Advisor to President Jimmy Carter, was working with Cardinal John Joseph Krol of Philadelphia to line up the American Cardinals behind Wojtyła. The CIA also got Krol to bribe cardinals from poorer countries (mostly from Asia and Africa) with CIA money to vote for the Polish Archbishop.

Andropov’s KGB had been following these activities, and as such his concerns about a US-backed plot were not unfounded.

The Polish Communist Party had, starting in late 1977, taken the diplomatic offensive in trying to undermine support for the controversial “neutron bomb”, a thermonuclear weapons designed to kill people by radiation rather than by the force of a blast. While such warheads had long been deployed on anti-ballistic missiles in the 1950’ and 1960’s, the Carter administration was looking to adapt them for use on systems like the short-range Lance missile, where they would be used to blunt Soviet armored divisions in case of a Warsaw Pact invasion of NATO. These weapons were very attractive to West Germany at the time, since the bulk of the fighting in any Soviet invasion would be done on its soil. “Neutron” warheads would kill Soviet soldiers without making German lands uninhabitable for centuries. But West Germany would not support the deployment of these weapons on its soil unless it had the backing of other European nations. The Polish diplomacy had been successful in undermining support for the “neutron bomb”, and in April 1978 President Carter formally announced that the US would defer production of the weapon contingent upon the Soviet Union doing the same.

The Carter administration, influenced as it was by the staunchly anti-communist Brzezinski, had an axe to grind with the Polish Communist Party. The election of Karol Wojtyła as Pope could help checkmate Poland’s influence among the major Social Democratic and Socialist parties of Europe.

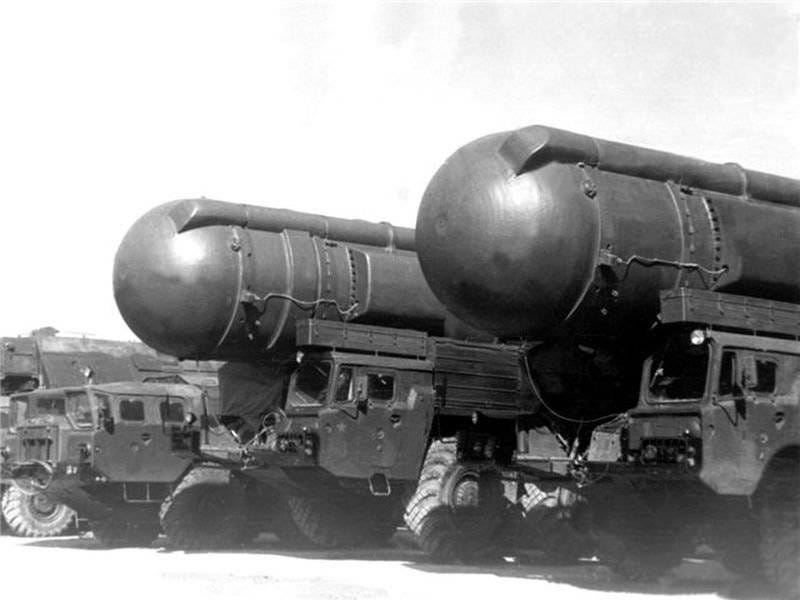

Shortly after as President in January 1977, Jimmy Carter was confronted by the deployment of Soviet SS-20 intermediate-range missiles within striking distance of Western Europe. The Soviet’s had already achieved strategic parity with the US in terms of strategic nuclear forces, and had likewise equalized the theater-level short-and-medium range posture through the deployment of the SS-12/22 “Scaleboard” solid-fuel missile. The deployment of SS-20 missiles, each equipped with three nuclear warheads, outside the range of any European-based counterpart weapons system created a capability “gap” that put the NATO “flexible response” deterrence strategy, premised as it was on deterring or countering Soviet aggression with an appropriate, graduated response—ranging from conventional defense to tactical or strategic nuclear weapons—at any level of conflict, at risk.

In August 1978, President Carter, with the strong backing of Brzezinski, approved a plan that he hoped would breath life back into “flexible response” by deploying a contingent of 108 Pershing II-XR ballistic and 464 ground launched cruise missiles to the United Kingdom, West Germany, and Italy. However, the question of Poland’s ability to influence the European mindset loomed large. To be able to overcome what was anticipated to be major European pushback to this plan, Poland needed to be neutralized. This is where picking Karol Wojtyła as Pope came into play.

In November 1977 my family moved from Ankara, Turkey, where my father, a Major in the US Air Force, had served as an advisor to the Turkish Air Force, to the Rheinland-Pfalz region of West Germany. My father was assigned to the 17th Air Force, headquartered at Sembach Air Base, where he oversaw aircraft maintenance in support of the 17th Air Force mission of conducting defensive and offensive air missions in Central Europe in support of NATO.

In times of crisis, the 17th Air Force headquarters staff would re-locate to underground bunkers where they could ride-out a Soviet nuclear attack and still fulfill their responsibilities.

In the fall of 1978, my family lived in a German home we rented from a German family that had been renting it out to Americans ever since General George Patton used it as a temporary headquarters for his Third Army in the final months of the Second World War. The home was on the outskirts of the German Town of Marnheim. Across the highway was a little village named Weirhof, home to a small military housing community which included a chapel, an officers club, bachelor officer’s quarters, and a medical clinic where my mother worked as a nurse.

Weirhof was located several miles from the US Army Special Weapons Depot in Kriegsfeld, officially known as NATO Site Number 107 but consistently referred to as “North Point.” Most of the families and officers living in Weirhof worked at “North Point”, where their mission was to secure and maintain the US Army’s inventory of nuclear 155mm and 8-inch artillery shells.

By the fall of 1978 I had become quite aware of the reality of life in West Germany. Simple daily existence put one in contact with tanks, helicopters and fighter aircraft as they traversed the fields and roads around my home, and the skies above it. The reason for this was the presence of two Soviet Guards armies (the 1st Tank and 20th Combined Arms) just over the East German border, some 200 kilometers (or 2 1/2 hours driving distance) away. I was told by my parents that if there was a war, we would not be evacuated, but rather would remain in place. It was expected that the Soviets could arrive within 2-3 days after the fighting began.

But I heard the other whispers—that the Soviets, in order to prevent nuclear artillery shells from being distributed to the US Army units who would be called upon to fire them in a desperate effort to stop the advancing Soviet tanks and armored personnel carriers, would hit “North Point” with nuclear weapons early on in the conflict.

Given the location of my families rented home to “North Point”, we were literally at ground zero of what would be the opening nuclear salvo of World War Three.

My father, given his work, would occasionally not come home at night. Instead he would be sequestered inside one of the underground bunkers located on the Sembach Air Base. For the most part, such occasions were linked to military exercises. But every now and then, the real world would intervene, and my father just disappeared without advanced warning. When this happened, he would simply call my mother and say two words—”Alas, Babylon.”

Alas, Babylon was the name of a 1959 book by Pat Frank which described post-nuclear apocalyptic life in a small Florida town. My parents had both read the book while my father attended the University of Florida—a time period which coincided with the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962. Needless to say, the book resonated deeply with both of them.

“Alas, Babylon” meant that the world could come to an end at any minute, this was not a drill, gather the family together and pray for the best.

October 16, 1978 was a Monday. My father had gone to work that morning as he always did, and my sister and I got on the rented German tour buses the Department of Defense used as school buses, for our 40-minute ride to Kaiserslautern, home to Kaiserslautern American High School.

I played football on the High School Football team (wide receiver/tight end), and after classes I would stay behind for practice, catching the “late bus” that would take me home to Marnheim.

The “Red Raiders” of Kaiserslautern were in the midst of what would turn out to be an undefeated championship season. We were coming off a decisive victory over Stuttgart Panthers, a game where I had made a critical contribution by catching a pass for 38 yards on third down that helped sustain what would prove to be the winning drive of the game.

That victory emboldened me to follow through on my plans to ask Betsy Ensign out to the Homecoming Dance, which was literally taking place on the next Saturday. I had made clear my intentions to all my classmates, so that no one would preempt my plans, but had yet to muster the courage to ask her out directly. My plan was to hang out at lunch in the classroom where Betsy’s mother taught social sciences, and wait for Betsy to show up. I was going to gauge from Mrs. Ensign whether or not I stood a chance before popping the question.

The plan worked like a champ—Betsy’s mom told me that Betsy was fully aware of my stated intention, more than a little angry that I was taking so long to answer, but most probably inclined to say yes if I just mustered the courage to ask the question. Betsy showed up, I asked her out, she said yes, and the world was perfect.

I went to football practice empowered only as a boy who had asked the girl of his dreams out to a dance could be. I was still on cloud none when I caught the late bus home, and looking forward to the opportunity to share the big news with my family.

But it wasn’t to be.

The selection of Karol Wojtyła as Pope had sent alarm bells ringing throughout Europe and NATO. The Soviets and their Warsaw Pact allies were hunkering down, trying to figure out how to respond. NATO, fearing the possibility of the Soviet’s taking advantage of their SS-20 missile advantage, upgraded their alert status.

My father was in the Sembach bunker.

And he had called my mother before hand, telling her the two words she did not want to hear: “Alas, Babylon.”

My mother and sisters and I spent the evening looking through family photo albums, talking about the adventures we had shared as a family, and afraid to go to sleep lest we never awaken. Eventually our eyes closed, and in the morning the sun came up, and we had to get ready to go to school.

My father was still in the bunker.

I remember looking out the bus window at our home as we drove away, wondering if I’d ever see it, or my mother, again. My little sister, Amy, attended the elementary school on Sembach, so I asked myself the same question about her. Suzanne, who was one year younger than me and in her Junior year, was with me on the bus. We didn’t say anything, but I knew she was worried as well.

Betsy and I met over lunch, since we were now officially “a thing.” She wanted my locker combination number, because there was a tradition of the dates of football players decorating the lockers the Friday before the game. She sensed something was wrong, but I couldn’t fully articulate the issue—Betsy’s family lived in the Vogelweh base housing located near the High School, far removed from the “North Point” weapons depot and the drama surrounding that location. Likewise, the fact that my father was in the war bunker, and had notified my Mom as such, wasn’t for public disclosure. I simply told her I was thinking about the game, and promised to be better company the next day, when we planned to meet for lunch.

But in the back of my mind I wondered if there would be a second lunch, a decorated locker, a football game, or a homecoming dance.

My father was in the bunker.

Football practice was as intense as one might expect it to be. I did my best to remain focused, but was taken aback when the sun reflected off the mirror on a truck driving past on Pariser Street, temporarily blinding me with a flash of brilliant light.

The only thought that went through my mind was “This is it.”

“Ritter, get your head screwed on straight,” Coach Joe Klemmer, who doubled as my physics teacher, shouted at me.

I did what I was told, but that flash, and what it could have possibly represented, shook me to my core.

I took the late bus home, scanning the driveway where the family car—a black Saab 99 Turbo—should have been parked.

It wasn’t there.

My father was still in the bunker.

He came home later that night, after we had eaten dinner. The Soviet reaction to the coronation of Pope John Paul II was determined to be purely political, and the threat of any military emergency had passed.

The world was good again.

Betsy decorated my locker, making sure to put a hand-made chocolate cake in their for us to enjoy together over lunch.

We won the football game in decisive fashion.

And I got to take my High School sweetheart to the Homecoming Ball.

A decade later, in October 1988, I was working outside the Votkinsk Missile Final Assembly Plant, nestled in the foothills of the Ural Mountains, some 750 miles due east of Moscow. I was at the time a First Lieutenant in the United States Marine Corps, working as an inspector assigned to the On Site Inspection Agency, a Department of Defense activity stood up in February 1988 for the purpose of implementing the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty.

The Votkinsk Missile Final Assembly plant was where the Soviets had produced the SS-12/22 and SS-20 missiles that had been at the heart of the “Pope” crisis of October 1978.

I was part of a team of American inspectors stationed outside the factory gates to make sure that these missiles were never again produced.

For me, this mission was particularly poignant.

The flash that I witnessed on the practice field in the late afternoon of October 17, 1978, was seared into my brain.

Helping rid the world of these weapons was personal.

People ask me why I’m so vested in the business of arms control.

It is not a difficult question to answer.

Because there was a time when a boy’s life was turned upside down by the existential threat these weapons posed to him, his family, and the life he lived.

Because my father had to go down into the bunker.

And before he went, he felt compelled to tell my mother two words that filled her with fear:

“Alas, Babylon.”

I believed in arms control because no mother should hear such words.

And no boy should have to wonder if the random reflection of light off a passing truck’s rearview mirror was the flash that signaled the initiation of a nuclear blast that would end his life in an instant.

The last remaining nuclear arms control treaty between Russia and the United States has expired.

My mission has failed.

I’m Marine Corps trained.

I won’t give up.

But I’m smart enough to know that the legacy of arms control that had kept the world safe for the past 54 years (since the signing of the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) treaty in 1972) has been squandered.

I will work to help make arms control a part of our strategic relationship with the other nuclear armed nations of the world, especially Russia.

But this will not happen overnight.

And my fear is that the next generation of children who otherwise should have been spared the consequences of events that caused a father to call his wife and utter the words “Alas, Babylon” will have to live through similar experiences as my own.

If, indeed, they can survive the experience.

(I will be travelling to Russia in March to continue my efforts to promote arms control and better relations between the US and Russia. As an independent journalist, I am totally dependent upon the kind and generous donations of readers and supporters to underwrite the costs associated with such a journey (travel, accommodations, meals, studio rental, hiring interpreters, video production and editing, etc.) I am grateful for any support you can provide.)

Another case when Soviets played responsibly, while being provoked.

Scott. Your example is indeed highly motivational and a rallying point for all who seek global peace and security. I respect your courage, perseverance and integrity.

Carry on dear Friend.

And God Bless